by Gwyneth Endersby, Record Assistant

Medieval music manuscripts at the County Record Office

Here at the Record Office, we hold several examples of medieval music – plainsong manuscripts, broadly covering the 13th to 16th centuries. None have endured in their original format, being pages, or just fragments in some cases, from liturgical books which did not entirely survive the dissolution of the monasteries. There may well be other music manuscripts amongst the records here, which have not yet come to light.

PR/MAS 3/1/1 Pages of medieval music found at the back of a volume of Masham churchwardens’ accounts and vestry minutes, 1542-1677

Whether wilfully destroyed, or abandoned due to their unpopularity during the Reformation, or simply hidden, the choir books or breviaries were at some point dismantled. The loose pages were later re-purposed, either as covers or as linings of significant, yet unrelated, documents and no details of their original provenance survive. As such, the medieval music fragments we hold are undated, yet we can be confident they are older than the dated records into which they were later incorporated.

PR/BED 2/1 Bedale churchwardens’ accounts (c.1576-1675), showing page of printed medieval music re-used as a cover and inside lining

Medieval plainsong: an introduction

Plainsong, also known as plainchant, is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Christian Church. The name refers to the unmeasured rhythm and monophony (single line of melody) of plainsong, as distinguished from the measured rhythm of polyphonic (multi-part) music.

Chants are typically sung during Mass or the Divine Office, and are either responsorial – where the soloist (or choir) sings a series of verses, each one followed by a response from the choir (or congregation), or antiphonal – where the verses are sung alternately by soloist and choir, or by choir and congregation.

Camaldolese Friars in Choir, by Zanobi Strozzi (1412-1468), c.1450 (public domain)

Music manuscripts were usually bound in large volumes, so that the whole choir and cantor could gather round them to sing. Specific choir books, such as graduals and antiphonals, were steadily replaced during the 14th century by compilations known as missals (for Mass) and breviaries (for the Divine Office).

Decoratively bound, these liturgical books were commonly donated to religious houses by wealthy patrons, the front cover bearing the name and status of the donor, the date, the name of the church or religious house, and so forth. In constant use from around the 12th century, a great many were destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries (1536-1540) and subsequent Reformation period. Any surviving fragments have usually lost the details of their provenance. Despite this significant setback, however, plainsong continues to be sung to this day.

Medieval plainsong: notation

Plainsong is written in neumes (from the Greek pneuma ‘breath’), which are notes sung on a single syllable, without meter. Notes were written on a four-line stave in major and minor keys, flat notes did not feature, as they were thought to be suggestive of the Devil!

The earliest neumes began appearing in Western Christian texts by the 9th century, and were freeform marks scripted above syllables in the text, a representation of hand-gestures indicating pitch direction.

ZJX 3/19/109 Example of ‘heighted’ neumes: detail from a music manuscript of the 14th century, reused as the front cover of a court book, 1600-1608

By the 11th century, ‘heighted’ neumes were written at varying distances from the text to indicate the overall shape of the melody. At around this time, Guido d’Arezzo introduced four staff lines (red), which clarified the exact relationship between pitches. Neumes then further evolved so that by the 13th century, the freeform notes were replaced by square notation, a version of which is still used in modern plainsong.

PR/BED 2/1 Example of printed square notation: detail from the inner cover of Bedale churchwardens’ accounts, c.1576-1675.

Mensural notation (measured music) evolved alongside neume notation, from about 1260 to 1600. It used different note shapes and colours (black, ‘white’: hollow, and red) to denote note values (timing), but there were no bar lines. Most polyphonic music uses mensural notation. In the late 16th century, mensural notation largely gave way to the modern system of bar notation, using a five-line stave.

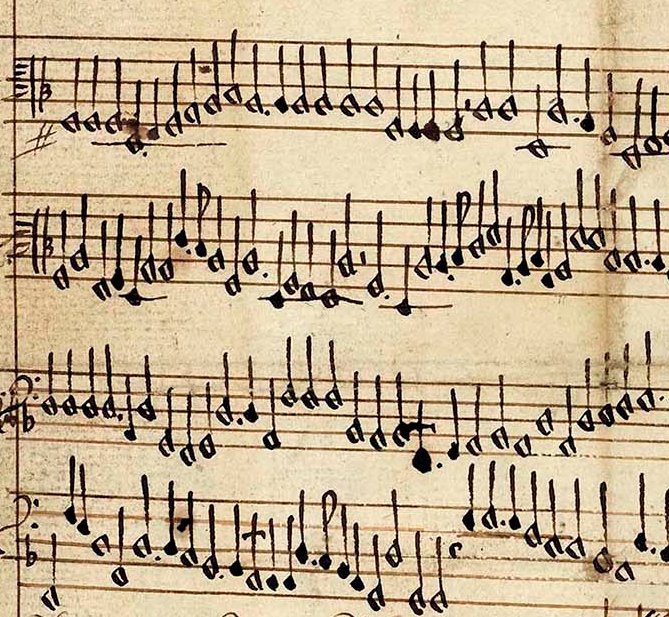

ZAZ 75/9081 (211) Example of mensural notation: detail from a polyphonic, secular song sheet ‘Phinetta Faire and Feat’, undated

Medieval plainsong: rubrics

Further instructions to the cantor and choir were made via rubrics and abbreviations. Rubrics (from the Latin ruber for red) are symbols written in red ink and inserted in the music manuscripts. The use of red ink indicates what should be done during a service (when to sing, respond), as opposed to what should be sung or recited (in black ink).

Standard abbreviations avoided unnecessary repetition of frequent recitals, and undue use of valuable parchment: examples include a ‘P’ with a cross at the base as a common symbol for Vespers, whilst a ‘V’ with a hatch on the right indicates ‘Response’. Another common abbreviation is e.v.o.v.a.e – at the close of a section. E.v.o.v.a.e is derived from key vowels in the last words of the Gloria Patri: ‘Saeculorum. Amen’.

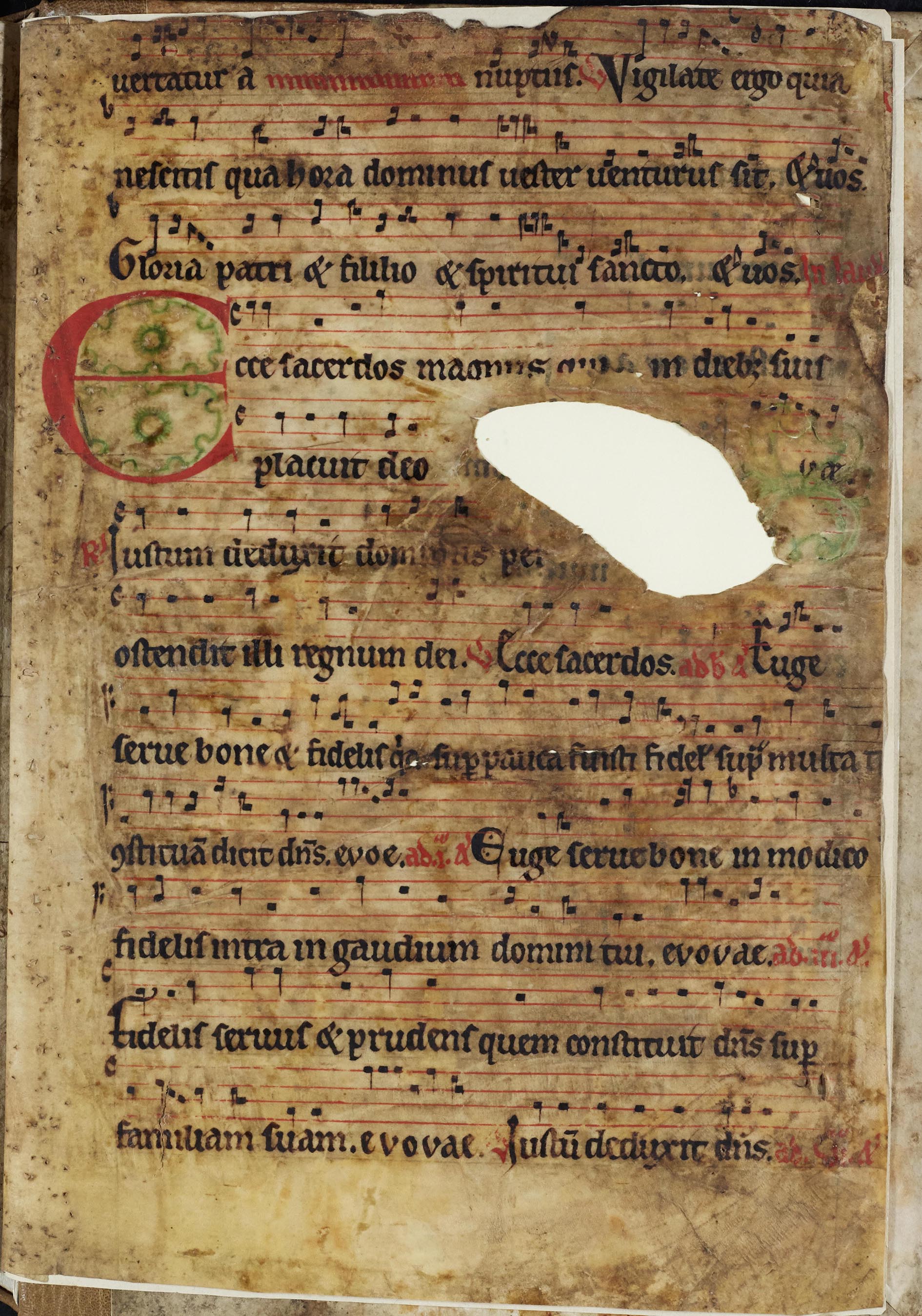

Left: ZJX 3/19/110 Detail showing rubrics, from the front inside cover of a court book, 1582-1608

Right: PR/MAS 3/1/1 Detail showing rubrics and the e.v.o.v.a.e command, from Masham churchwardens’ accounts and vestry minutes, 1542-1677

Monophonic examples

Plainsong fragments feature as bindings of church records, such as parish registers and churchwardens’ accounts.

Part of a music manuscript re-used to cover and line Bedale churchwardens’ accounts, c.1576-1675, is 16th century in appearance, with formally printed square neume notation (PR/BED 2/1, see below). Its format suggests it nonetheless pre-dates the re-organisation of the Roman Missal (the book containing all texts used to celebrate Mass) by Pope St. Pius in 1570, which eventually replaced the widespread use of different Missal traditions.

PR/BED 2/1 Bedale churchwardens’ accounts (c.1576-1675), outer cover (left) and linings of printed medieval music (right)

Cut and folded during the binding process, the outer edges of the music manuscript shown above are missing or damaged. Also, through centuries of handling, the notation is now barely discernible on the outer cover. The inner back page, however, is recognisable as a Gradual, the first chant sung at Mass with texts taken mainly from the Psalms. Graduals are believed to be so named because they were commonly sung on the step (Latin: gradus) of the altar.

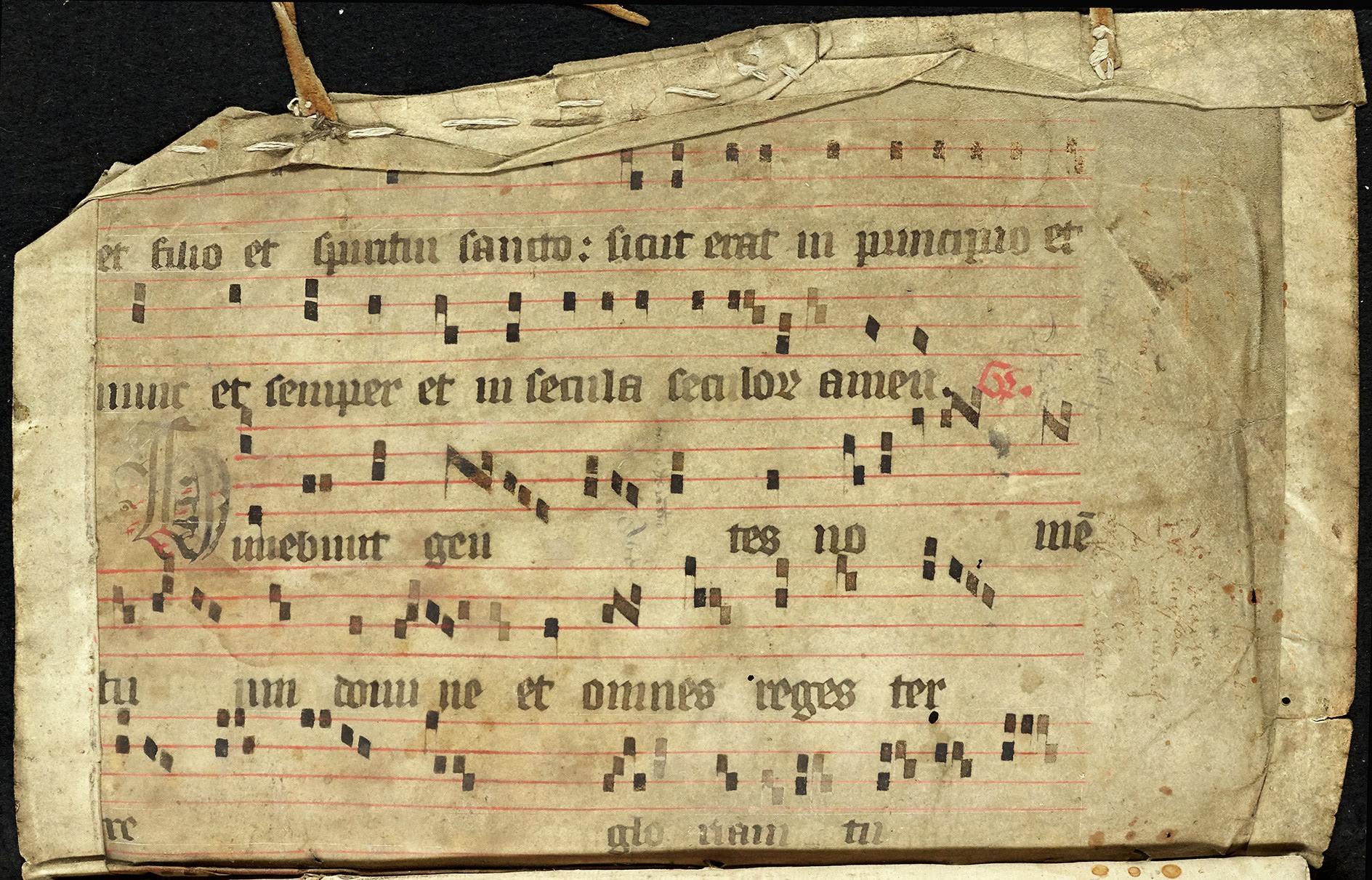

Folios of a medieval music manuscript were once used to line the outer cover of Masham churchwardens’ accounts and vestry minutes, 1542-1677, but later have been grouped together at the end of the volume during a modern re-binding (PR/MAS 3/1/1, see below). They are pages from an antiphonal: the music for Vespers, being a set of antiphons (short pieces of text sung alternately by cantor and choir, or two choirs) followed by Psalms. Cut and trimmed during re-use, some of the music has been lost. The notation is 15th century in appearance.

PR/MAS 3/1/1 Masham churchwardens’ accounts and vestry minutes, 1542-1677. These pages of medieval music feature the parable of the wise and foolish virgins

During the re-binding process of the churchwardens’ volume by our conservation department, fragments of a music manuscript were discovered, which had been re-purposed as spine-supports (see below). They are possibly part of the same music manuscript as the cover lining pages and are kept in an envelope with the volume.

PR/MAS 3/1/1 Fragments of a music manuscript used as spine supports in an historic binding of the volume

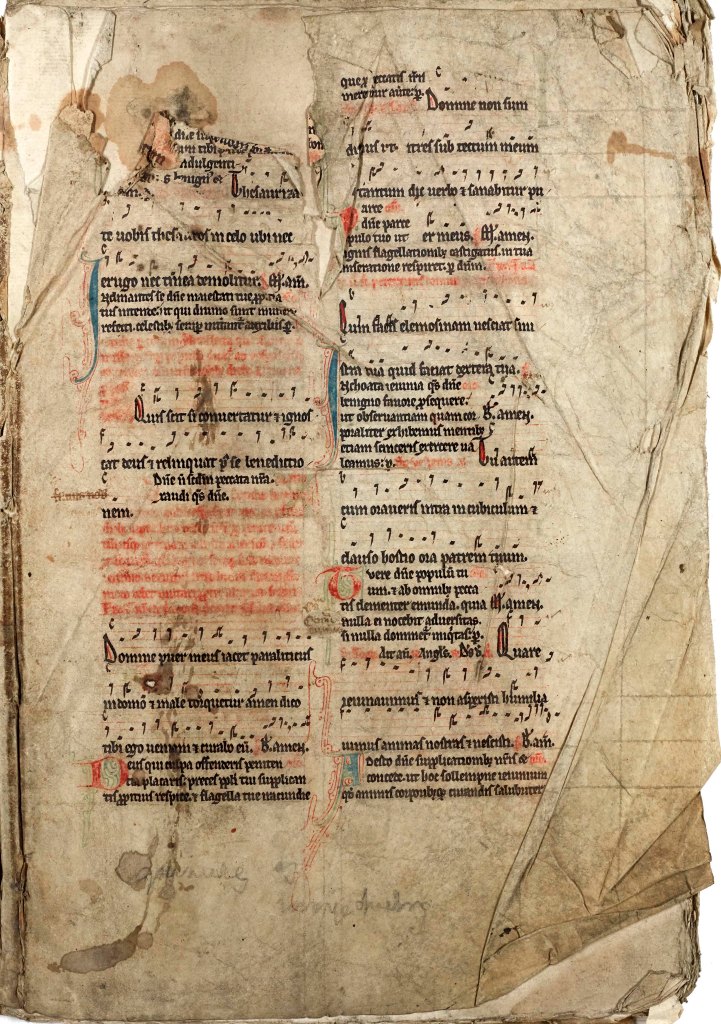

Manor court books of the 16th and 17th century in the Jervaulx Abbey estate archive (ZJX) include examples of monophonic music manuscripts.

One is a possible 14th-century, rather decayed, illuminated music manuscript in ‘heighted’ neumes, re-used as a cover for court rolls relating to Tornock, Somerset, 1600-1608. The text comprises key fragments of Psalms, rather than the full versions, as the choir usually learnt these by heart. It is the plainsong for Vespers – the red rubric symbol of a ‘P’ with a cross at base being a common abbreviation for this office.

ZJX 3/19/109 Folio and verso of a music manuscript, re-purposed as the front cover of a court book for Tornock, Somerset, 1600-1608

ZJX 3/19/109 Folio and verso of a music manuscript, re-purposed as the back cover of a court book for Tornock, Somerset, 1600-1608

Another illuminated example, again somewhat decayed and possibly 14th century in date, has been re-used as a court book cover for Lympsham Parva, Somerset (1582-1603). Turned upside down to make full use of the wide base margin, the cover bears the court roll dates and name of the landowner.

ZJX 3/19/110 Folio and verso of a music manuscript, re-purposed as the front cover of a court book of a court book for Lympsham Parva, Somerset, 1582-1608

ZJX 3/19/110 Folio and verso of a music manuscript, re-purposed as the back cover of a court book for Lympsham Parva, Somerset, 1582-1608

Part of an ‘Allelulia’ chant, in square neume notation, has been re-used as the cover of Richard Cholmeley of Brandsby’s personal notebook c.1622 (ZQG XII 3/1). Alleluias – Praise the Lord! – were lively and decorative interludes sung at major Christian celebrations such as Easter and Christmas. Often highly illustrated music manuscripts, this example is a relatively simple Alleluia, c. late-15th century.

ZQG XII 3/1 A c.15th-century Alleluia chant used as a notebook cover, c.1622. The left image shows the outer cover in entirety, whilst the right image shows detail of the front cover, including the decorative capital letter ‘A’s

Whilst medieval music manuscripts are by no means exclusive to the County Record Office, it is quite possible that the pages we hold here are unique in themselves, specially commissioned as they were by the patrons who gifted the original service books to their chosen religious house(s).

In addition, we hold amongst the undated, miscellaneous papers of Archbishop Matthew Hutton of Marske (ZAZ) a secular polyphonic music manuscript showing ‘white’ mensural notation.

Typical of 15th-16th century-style, it is complete with lyrics for a rather doleful love song called Phinetta Faire and Feat.

ZAZ 75/9081 (211): Music and lyrics for ‘Phinetta Faire and Feat’, handwritten on paper, undated

Sources, acknowledgments and further reading

Grateful thanks to Father Anselm Cramer of Ampleforth Abbey, and to Chris Mason and John Henderson, members of the Northallerton Latin group (who meet regularly at NYCRO), for translation from Latin to English and assisting with interpretation of the rubrics and abbreviations in the music manuscripts held here.

Camaldolese Friars in Choir, by Zanobi Strozzi, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Royal School of Church Music: Plainchant Resources webpage

Above is a sample of the Kýrie Eléison (Orbis Factor) from the Liber Usualis, in neume notation. Listen to it interpreted via the Wikipedia Plainsong webpage.