By Gail Falkingham, Record Assistant

This blog is the second in a two-part series exploring the journals of Joshua Samuel Crompton (1799-1881) and William Blane (1800-1825), which describe their travels through Sicily between the 8th and 19th February 1825. The first part covered their journey by sea from Naples on the west coast of Italy, to the port of Messina on the north-east coast of Sicily, and then southwards down to Catania. This second part covers the latter half of their journey from the 14th to 19th February, from leaving Nicolosi to climb Mount Etna, and then riding further south to Syracuse to see the ancient sites, including the remains of Greek temples, the theatre and museum, before setting sail for Malta on 20th February.

A note on the illustrations: these travel journals contain text only, extracts from which are cited below. To illustrate the ancient sites they describe, images of near-contemporary paintings and drawings have been reproduced under licence from a number of public collections, to whom we are most grateful.

View of Etna during an eruption at night by Victor Jean Baptiste Petit, 1828-1863, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-2018-3414), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

February 14th 1825 – climbing Mount Etna

In part one, we left our travellers at the inn in Nicolosi, having had an early night in preparation for their ascent of Mount Etna. The next morning, on the 14th, they were up very early, so as to arrive at the foot of the volcano by daybreak. They set off on mules, riding through woods, but soon encountered deep snow and were obliged to proceed on foot.

Crompton described this first part of their journey:

“Rose at 3 in the morning, and after having refreshed ourselves out of our estimable kettle, started in the dark for our hazardous enterprise, we left the inn at about half past 4, and having in the dark walked nearly 2 hours on the lava, which is very difficult to ride over, when light began to appear found ourselves entering the woody region, we had not gone above half a mile, when we found the snow so deep, and so hard, that the mules could not proceed as it broke with their weight, and sunk so deep that they could with difficulty extricate themselves, we were then obliged to leave them, and as it was so very fatiguing I left my gun also, we started for the ascent, most of our party were so cold and benumbed with cold, they could hardly stand when off horseback, but I did not suffer having good coats, and thick boots and stockings, in about an hour’s good walking we passed through the woody region and entered on the steep ascent of the mountain, which the more you ascend the higher it looks…”

Blane described his first sight of the volcano:

“The whole of the mountain … appeared one entire mass of snow with the exception of here and there a few black spots of ashes and lava peeping through. I could have fancied myself on one of the high Alps had it not been for the superb column of smoke rising from the summit.”

Crompton recorded the start of their ascent and the beauty of the sunrise:

“… we each took a roll of bread and an orange in our pockets, and a small pocket bottle holding about a tumbler of whisky for all. We went in this way till nearly arrived half way up the first ascent. The sun rising out of the sea was magnificent, we were not high enough to see it in full glory, but what we did see quite satisfied me as being one of the most glorious sights I had ever beheld. The sun became so powerful in a short time as quite to be oppressive, and by the time we had mounted a little higher the heat was so great and the reflection on the snow so powerful, that we could hardly bear to open our eyes, one of our party, Mr Blane, felt it severely, making him giddy and his head ache violently.”

Winter view of a snow-capped Mount Etna, published by John Harding, 1815 © Wellcome Collection (43893i), shared under public domain mark 1.0 universal

At this point, Crompton separated from the group and went on ahead, frustrated by the slow progress of his companions:

“It was here that finding the snow was melting fast on my boots, and consequently making the feet intensely cold by the rapid evaporation, I left the party attended by one of the guides… others of the party wished to stop frequently which I did not think prudent to do so I started, in the morning the snow was in most places hard enough to bear your feet, only occasionally breaking through the crust, and then only sinking a short depth, not quite otherwise, the labour was immense, and the heat of the upper part of the body and the coldness of the legs, was the only objectionable part of the trip, this certainly was very severe.“

The deep snow, uneven terrain, heat of the ash and sulphurous gases emitted by the volcano made the ascent a challenging and tiring one:

“The whole ascent from here is very bad, you pass over snow dirty and soft from the smoke which was drifting down the mountain-side and which covered it so thick with small ashes, as to make a crust in some places … I sunk up to my middle repeatedly, and the uneven crevices make it when this happens both dangerous, and difficult, in about half an hour’s stiff walking I passed over the extremity of the snow, the ground now becoming so hot as to melt the snow as fast as it falls. Soon after this I arrived at the top, the crater was smoking very greatly, and if I felt at the time fatigue, every idea of the kind vanished when I beheld the magnificence of the scene.”

A few weeks earlier, on 31st January, during their stay in Naples, Crompton and Blane had also climbed Vesuvius, and both made comparisons between the two volcanoes in their journals.

Crompton wrote of Etna:

“The crater is not larger than the present one of Vesuvius, but quite different, it is nearly circular, but one side is cut off so nearly flat as to enable another small crater to be seated on this side, this seems to send forth nothing but sulphur, the descent on all sides is pretty equal, in the centre is the crater, the immense quantity of smoke that issued when we were there quite hindered us from having any idea of the inside of this terrific aperture, the colour of the smoke is purple, red, orange, green, and all blended together into a beautiful blue when it has ascended some height, the roar that every now and then issues from the aperture is quite horrible, the rumbling like thunder but more terrific, perhaps occasioned by seeing the cause of the sound, the smoke is continual, but every 10 or 15 minutes when we were there it burst out with more vehemence, quite enveloping everything in darkness for a minute, nothing on earth can give a man the idea of the vastness of the creation so much as this Eternal fire, which has blazed since the creation…“

Inside the crater of Mount Etna by Willem Carel Dierkens, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-65), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

After admiring the view from the summit, Crompton descended and on his way down passed his companions, who were still climbing up. On reaching the foot of the volcano, he removed his wet clothes and slept by the fire for three hours until they returned. His impression of the summit:

“… The view from the top exceeds belief, which you may well imagine when this is 10,000 feet high and more from the sea, and it rises from it on every side… the view from Etna alone would quite repay anyone, you entirely see the extent of Sicily on all sides, on no side was the view bounded by land except near Palermo… the thermometer at the top was 23 [degrees] when in the air, when on the ground 97 instantly, and was rising fast when we took it away. I soon was so cold by the wind and the smell was so oppressive, that I descended, and met my friends near the Casa Inglese ascending… I had some difficulty in tracing my road back, but at length I did. On finding the mules, I made a large fire and dried my clothes, which were much wet, my shoes and stockings up to my knees, in this way I slept 3 hours till the rest of the party returned. They were miserably cold.“

Meanwhile, at 1 o’clock, Blane had also reached the summit. He noted that they had walked twelve miles from where they’d left the mules, and taken four and a half hours to do so. He wrote:

“We remained an hour and a half on the summit, enjoying the magnificent prospect and examining the surrounding country and its towns with a telescope… Descended, mounted our mules and arrived at Nicolosi about 1/2 past 5. After taking a little refreshment (tea which we made in our kettle and which is the most refreshing thing a traveller can take), we again mounted our mules and arrived at Catania at ten o’clock pm.“

February 15th – resting, and visiting the opera in Catania

Crompton recorded arriving in Catania the previous evening “a good deal tired.” They had been planning to travel on next to Syracuse, but because they slept in that morning owing to their tiredness from their exertions climbing Etna, it was too late to do so in a single day. An overnight trip would have necessitated a longer journey, so they stayed in Catania an extra day, before heading to Syracuse on the 16th:

“…if we made two days of it, we should be obliged to go round 16 miles by Lentini, as that was the only place we could sleep at.”

They went out to have another look around the town of Catania, but bad weather changed their plans and so they returned home. In the evening, they visited the opera to see ‘Il Turco in Italia’ by Rossini:

“…it was so unpleasant a day we returned home, in the evening went to the opera ‘Turco in Italia’. This being the last day of the Carnival, this was a treat to the inhabitants, who, on account of the death of the King, had been deprived of that amusement.”

Prior to the unification of Italy in 1861, Sicily and a large part of southern Italy was ruled by the King of the Two Sicilies. On 4th January 1825, just a few weeks prior to Crompton’s arrival, King Ferdinand I had died. He had ruled since being restored to power in 1816 after the Napoleonic Wars, and was succeeded by his son, Francis I.

February 16th – journey to Syracuse

To reach their next destination in a single day, they set off early in the morning; Crompton recorded:

“Rose early and started for Syracuse, we were on our mules before 6 as we had a 42 miles journey.”

Distant view of Mount Etna, near Catania, drawn by J. Smith & engraved by W. Byrne and T. Medland, 1788 © Wellcome Collection (43892i), shared under a public domain mark 1.0 universal licence

They rode across the plain of Catania from which, Blane commented:

“… is the finest view of Etna. You see it rising magnificently from the plain which is almost level with the sea... It presents a most splendid scene for a distant landscape.“

Both writers described the landscape they passed through in some detail, commenting upon its flora and fauna, as well as noting the poor condition of the roads. Crompton wrote that they:

“were in a great hurry to reach Syracuse before the gates are closed.” They arrived in time, and “were glad to get some supper and go to bed”.

En route, they also passed the pillar of Marcellus (the Roman general who captured Syracuse during the Second Punic War, 218–201 BC). Blane recounted:

“Before arriving at Syracuse we passed a ruin composed of large square stones. This is said to be the trophy erected by Marcellus after he had taken Syracuse. The whole distance from Catania to Syracuse – 42 miles is without the least appearance of a road.“

Base of a colossal column near Syracuse, drawn by Luigi Mayer, engraved by William Watts, 1810 © The New York Public Library (b10155031), shared under a public domain licence

Syracuse

In the south-east corner of Sicily, the coastal city of Syracuse originated as a Greek colony founded by Corinthians in the eighth-century BC on the island of Ortygia. This was one of several Greek colonies founded across Magna Graecia in Sicily and southern Italy. Some of the most distinctive and well-preserved remains of these Greek settlements are the monumental archaic Doric temples, built to honour the gods, commemorate major victories in battle, and as symbols of wealth, status and Greek identity. Two such temple sites in Syracuse were visited and described by Crompton, neither as large or well-preserved as those in Akragas and Selinous, but important survivals, nonetheless. He also visited several other ancient sites, as detailed below.

In 1787, whilst Goethe, the German writer and poet, claimed:

“To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is not to have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything”, he did not see Syracuse as he had “…heard that little now remained of that once glorious city but its name”. In this, he was clearly misinformed.

Goethe in the Roman Campagna, by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829), 1787 © Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main (no. 1157), public domain

February 17th – the ancient sights of Syracuse

During his short stay in Syracuse, on 17th February 1825, with his travel companions and a guide, Joshua S. Crompton had a long and busy day visiting the city’s numerous ancient sites, including the ‘Peritoneum’ (Temple of Olympian Zeus), the amphitheatre, theatre, nymphaeum and latomia (quarries), the Ear of Dionysius, the Tomb of Archimedes, the cathedral and remains of the Temple of Athena, the catacombs and museum, and finally the Fountain of Arethusa. He wrote of the start of their day:

“Rose tolerable early, and formed a large party to see the celebrated ancient remains, we procured a guide who was a rather intelligent man, and who had made some good drawings of these ruins, we left the town by the same entrance we had come in by in the evening, and which I have since found out is the only one…”

The Temple of Olympian Zeus

On a hill above the town, Crompton’s first visit was to his so-called ‘Peritoneum’, aka the Temple of Olympian Zeus, built in the sixth-century BC. Only two partial columns and the stereobate of the structure remain. This represents a civic cult outside the walls of the city in the sanctuary of the god. Originally a long, narrow building, it is estimated that the entire structure measured c.20.5m by 60m, with a plan of six by seventeen Doric columns, with a double colonnade at the front of the naos. Of this site, Crompton wrote:

“Leaving the shore we ascended the hill above the modern town, on the flat before you enter on the rock, there are the remains of the Peritoneum, which I understand was the school for the students to dispute in, only two pillars now remain, the bases of several are yet remaining, and I inspected them, the pillars have been raised to their recent situation not many years back, as evidently the whole of the ground has been raised by rubbish, as these bases have been excavated 3 or 4 feet.”

Fragments of two columns of the Zeus Olympus temple, Syracuse by Louis Mayer, 1778 © Rijksmuseum, (RP-T-00-493-71A), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

The amphitheatre

The Roman amphitheatre, like the earlier Greek theatre of Syracuse (see below), is cut into the hillside in the ancient suburb of Neapolis. Little of the superstructure of the amphitheatre remains and it was not excavated until 1839, a few years after Crompton visited the site. He noted how both this, and the nearby site of the Greek theatre, had been used as a source of stone building material by Charles V, who was Holy Roman Emperor and also King of Sicily in the first half of the 16th century AD, to build new fortifications on the island of Ortygia.

“… From here we went to the Amphitheatre, which is only small compared with the other ruins which are so splendid, it is imagined this was constructed by the Romans after the capture of the city, it is hewn out of the solid rock, and is perfect on the upper side, the lower, being composed of hewn stone, was taken away in the same manner as was the scena of the theatre by Charles the 5 to make the fortifications for the modern town…”

The theatre

The Greek theatre at Syracuse is the largest ancient theatre on the island and one of the largest in the Greek world. The second largest theatre in Sicily is that at Taormina, visited by Crompton a few days earlier on 12th February. Measuring just under 140m in diameter, the theatre at Syracuse was originally built in the 5th century BC and subsequently extended and modified in the 3rd century BC, and again in the Roman period. The stage is surrounded by a semi-circular arrangement of 67 tiers of seating for the audience, cut into the rock of the hillside. This seating (the cavea) is divided by steps into nine sections, each one known from inscriptions to have been dedicated to a deity or member of the royal family. The whole site overlooks the island of Ortygia and coast below and is still used for performances today.

Remains of the Greek theatre at Syracuse attributed to Louis-François Cassas (1756-1827), via Wikipedia Commons, public domain

Crompton described the theatre:

“…after leaving the amphitheatre, we went to the [Greek] theatre, which is also all cut out of the solid rock, except the scena [building at the rear of the stage], which being on the south side, and on the declivity of the hill, was composed of hewn stone, this as before mentioned was carried off by Charles V for the use of the town, the theatre is of a great size, our guide told us the largest in existence, whether this is the fact I do not know, but certainly it is not much larger than the one at Taormina, it is much spoilt by a modern aqueduct which passes through the centre, the steps of this are of a curious construction, as there is a ledge which prevents the feet of the upper person from touching the one below.”

Interior of the theatre in Syracuse by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-83), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

The Nymphaeum and latomia quarries

Above the theatre, on a terrace cut into the rock, they visited what is known today as the Grotta del Ninfeo, where water from an ancient Greek aqueduct flows out into a large basin. This is thought to have been the site of an ancient sanctuary to the muses, where actors would have gathered before performances at the theatre below.

“Just above this place is the Nymphaeum where a statue of Apollo stood, the only use now made of this excavation is to wash in, we saw numbers of women performing this employ. To the left as you stand with your back to the theatre opposite to the Nymphaeum is the street leading to the Tombs. This is also cut out of the solid rock.

The Grotta del Ninfeo by Jean-Pierre Houël, c.1776-1779, via Wikipedia Commons, public domain

“We left this place and returned towards the modern city for about 2 or three hundred yards, when we descended into the Latomia, literally meaning the stone quarry, from ‘laos etriphona’, this is an immense excavation of a great depth, and of a huge circumference, this was the place where the Athenian prisoners were confined, when they who could not repeat certain passages out of Euripides were destroyed.”

Part of Latomia caves near Syracuse which used to serve as a prison by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum, (RP-T-00-493-78), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

Ear of Dionysius in a corner of the quarry

The Ear of Dionysius is so called because of the ear-like shape of an opening in the rock, named after Dionysius, a renowned Greek tyrant of Syracuse. Crompton described the cave in the rock behind:

“In one corner of this place is the celebrated excavation called the Ear of Dionysius. The whole of this is highly interesting. I was much surprised at the vast extent of the place, it is 70 yards long by 11 wide, the height is different, not so high at the entrance, but gradually rises in the centre, at the entrance I should guess it to be about 60 feet high or not quite so much, but at the middle 80 or 90, the top of this gradually is formed into a sharp arch, where there is a channel cut about 2 feet wide and one deep, this is supposed to have been made to convey the sound …“

- Left: Exterior view of the Ear of Dionysius by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-80), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

- Right: View of the entrance to, and interior, of the Ear of Dionysius and latomia by Jean Claude Richard, Abbé De Saint-Non, 1786, via Picryl, public domain

He also debated its function:

“… various are the conjectures concerning this extraordinary place, which is shaped exactly like an asses ear at the entrance, and winds something in this shape. Some suppose it had a communication with the theatre, and was made to produce thunder or other supernatural sounds, while many still maintain that it was made for the common vulgar opinion of hearing what the prisoners said, a pistol was fired at the entrance, and the report was so terrific, as not only to be heard but felt, the sound seemed to strike on all sides of your person, a kind of tremulous feel quite different from what I have ever experienced.”

Blane, on the other hand, was rather more cynical:

“That part of it called the Ear of Dionysius affords a curious specimen of the facility with which any absurd fable is swallowed. On inspecting this really curious excavation nothing can be more evident than that it never could have been intended for an ear. It is only on account of the small duct at the top that antiquarians have puzzled their heads upon the subject. It must ever remain doubtful for what purpose this was made. It was supposed to terminate at the further end; but my cicerone told me that a short time before, he took refuge from a violent shower of rain in this place, and that the water poured in from the point where the small duct appeared to terminate in the solid rock. Where could this have led?“

The Tomb of Archimedes

Archimedes was an Ancient Greek mathematician and scientist from Syracuse, who lived in the 3rd century BC. In 75 BC, whilst a quaestor (public official) in Sicily, Cicero believed he had discovered his tomb, recording the moment of discovery in his Tusculan Disputations (Book V, Sections 64-66):

“… I will present you with an humble and obscure mathematician of the same city, called Archimedes, who lived many years after; whose tomb, overgrown with shrubs and briars, I in my quaestorship discovered, when the Syracusans knew nothing of it, and even denied that there was any such thing remaining: for I remembered some verses, which I had been informed were engraved on his monument, and these set forth that on the top of the tomb there was placed a sphere with a cylinder. When I had carefully examined all the monuments (for there are a great many tombs at the gate Achradinae), I observed a small column standing out a little above the briars, with the figure of a sphere and a cylinder upon it...”

- Left: Tombs with facade in Doric style cut in rock in the vicinity of Syracuse by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-75B)

- Right: Plan of funerary monument with Doric columns carved in rock and located 2 miles from Syracuse by Louise Mayer, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-74A), both shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

Crompton and his companions visited the tombs outside the city gate, including the so-called Tomb of Archimedes but, familiar with Cicero’s description, they had doubts about its attribution. Crompton wrote:

“From this place we went to the road leading from the town to the ancient road to Messina, and Catania, the very one we came down the night before, these [tombs] certainly are more worth seeing than any other things I have seen, they are all cut out of the solid rock, and are ranged one above another, some of them holding one and two and from this to 10. They are so small that they could only hold the bones, one of these places, I know not with what truth, is called the Tomb of Archimedes, it is quite by the side of the ancient road, and so far accords with the description given by Cicero, but how it could ever stand by itself, and be covered with thorns and briers, I think in its present situation was impossible, it at present has an ornament above the entrance…, but it has in the inside 6 niches which seem to indicate that it belonged to a family, and as to standing by itself it has 5 or 6 others joined to it…”

Blane expressed his reservations more strongly:

“… Among others, one, which with inconceivable ignorance and impudence has of late been denominated the tomb of Archimedes. It is a large and conspicuous tomb cut in the rock close to the principal ancient road; and never could have been hid in brushwood and brambles as the real one described by Cicero. Indeed the only reason why it has been called the tomb of Archimedes is that it is the most conspicuous, most ornamental and in best preservation.“

Our travellers were right to be sceptical about its attribution, as this tomb is now believed to be Roman in origin.

The catacombs

After spending some time wandering around the roadside tombs, they went to see the catacombs, a network of underground tunnels beneath the city, now known to contain c. 10,000 Christian burials. The entrance is described by Crompton as being by an old church. This is most likely referring to the Byzantine Basilica of St. John the Evangelist. Of the catacombs he wrote:

“… we descended into this place, and were highly gratified, they are very extensive, and are cut in the solid rock. They are in avenues, and here and there funny excavations, some made for the body full-length, others only made in niches to hold an urn or bones, the date of this is not known, and the extent has not yet been fully known, but they are very difficult to find out, a stranger would soon be lost.“

Plan and view of the catacombs in Syracuse by Jean Claude Richard, Abbé De Saint-Non, 1786, via Picryl, public domain

Blane also marvelled at what he saw:

“… we went to the catacombs, which are of very great extent and are most curious and interesting. Hewn and excavated in the solid rock, they remain a perfect monument of the extraordinary pains taken by the ancient inhabitants in burying their dead.“

The statue of Venus at the museum

“When we reached the town we went to the Museum, which is a small collection of coins, bases, marbles and armour one being the pet of this collection is certainly a fine statue, the drapery well done, the head is lost, and part of the right hand, which is placed nearly in the same position as the Venus of Florence, she in her left hand holds the drapery covering the modista, the drapery coming from behind, and held by the left hand in a bunch.”

This description matches that of the statue of Venus Landolina, now housed in the Paulo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum in Syracuse. Discovered in 1804, this statue was named after its finder, Saverio Landolina (1743-1814). It is also known as a Venus pudica, or ‘modest Venus’, because the unclothed Venus is covering her modesty with her drapery. Made in the 2nd century AD from Greek marble, it was copied from an earlier Greek sculpture of the 2nd century BC.

Sculpture of Venus in the museum of Syracuse photographed by Giorgio Sommer (1857-1914) © Rijksmuseum (RP-F-F16742), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

The Temple of Athena

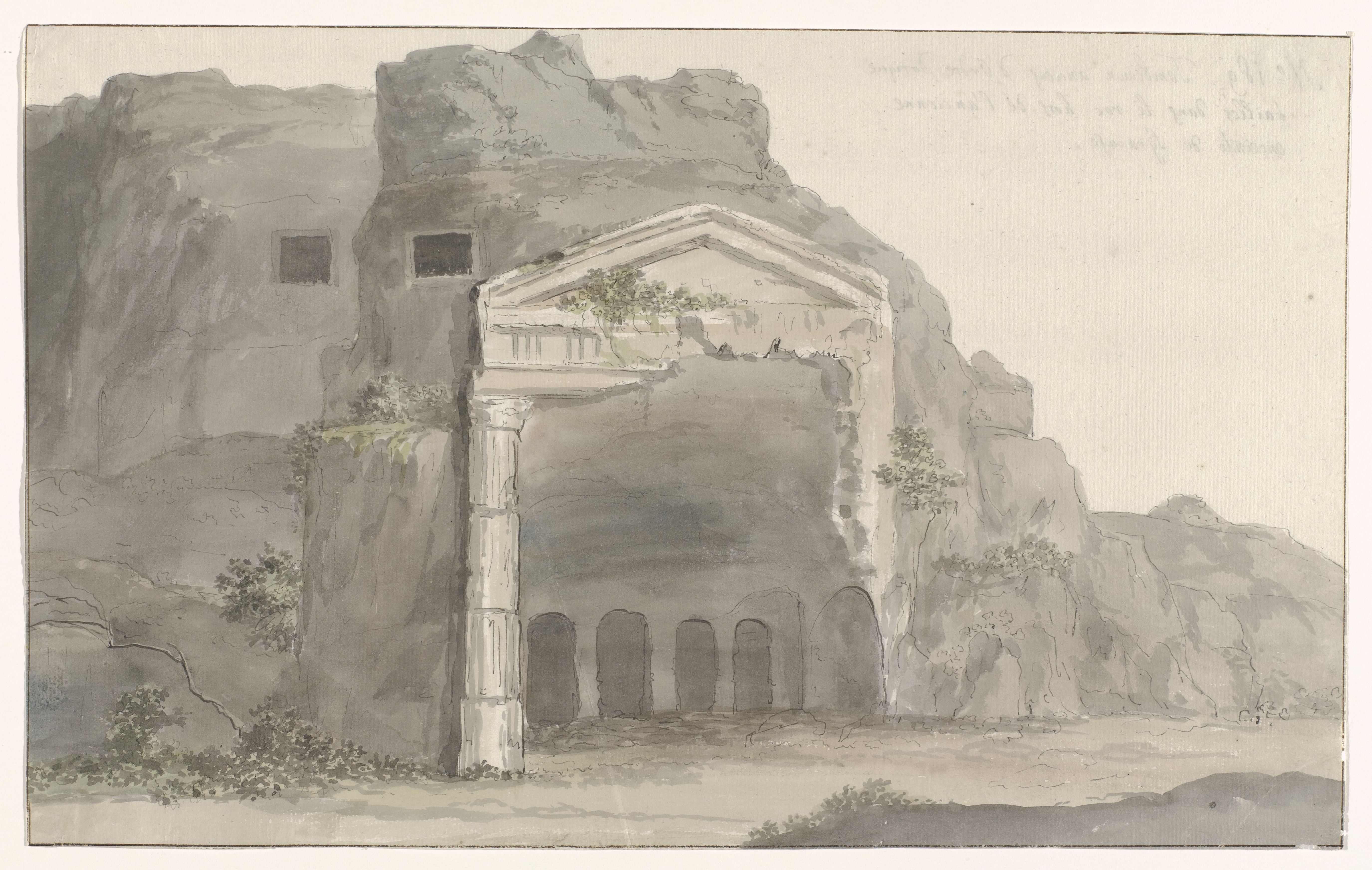

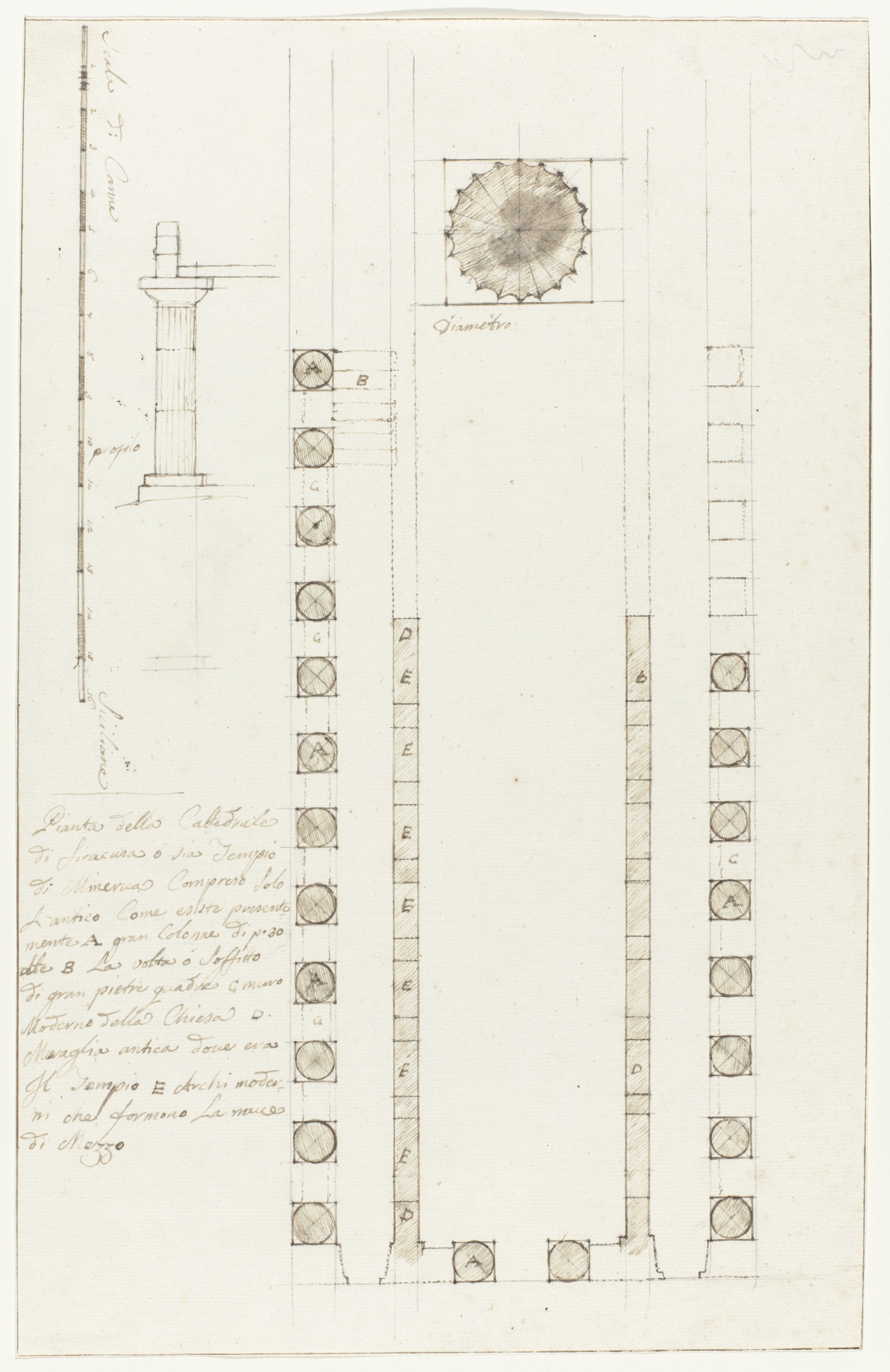

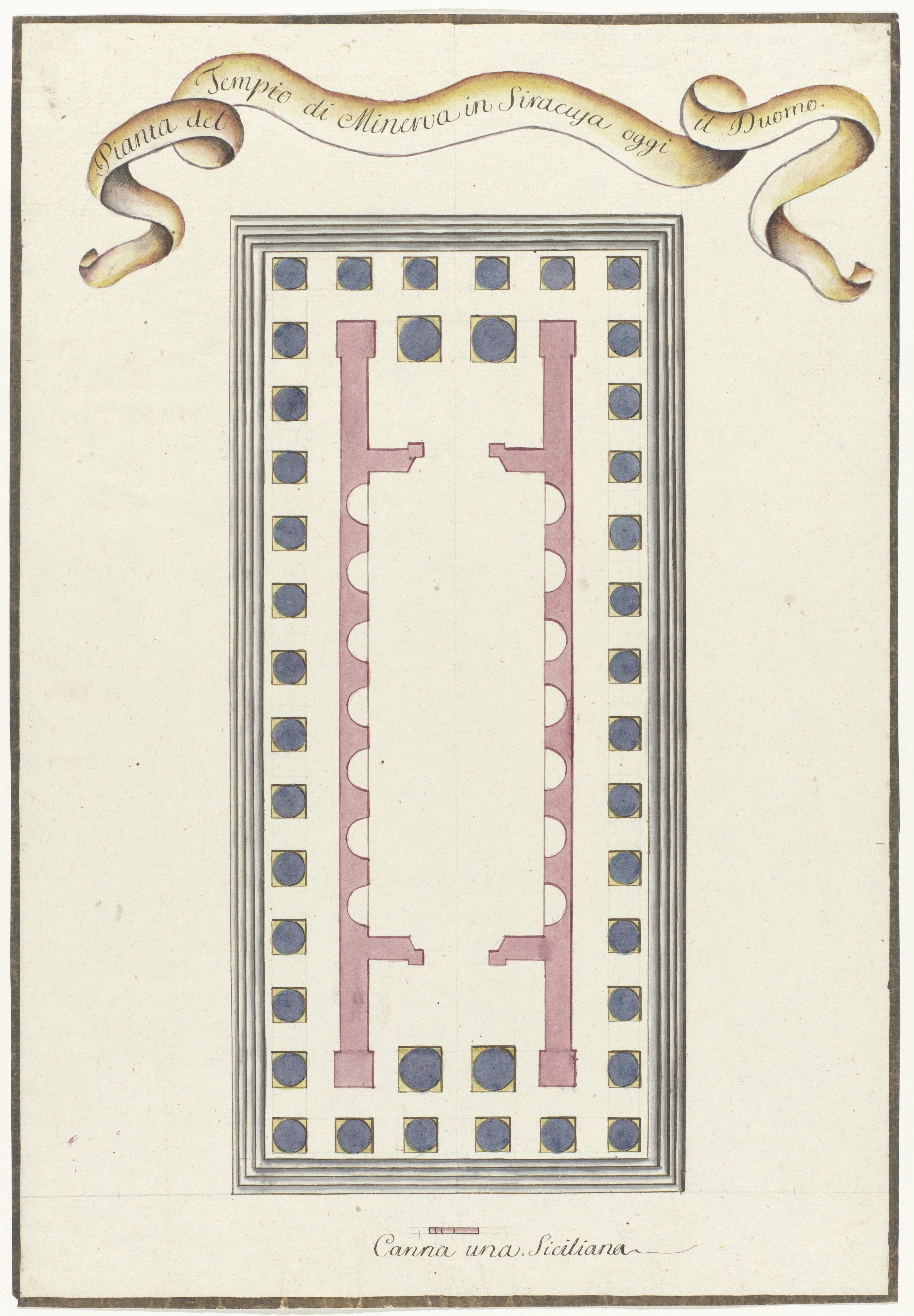

After visiting the museum, Crompton saw the cathedral at Ortygia, the Baroque façade of which was redesigned by Andrea Palma from 1728-53. The building has seen a number of religious uses over the centuries, its outer walls infilling the spaces between, and thus preserving, the Doric colonnade and part of the frieze of the Temple of Athena (previously known as the Temple of Minerva). Originally erected between 475-470 BC, it has a peristyle of six columns at the front and fourteen along the sides. Of this temple, Crompton noted:

“Just opposite to the museum is the Cathedral, which has an ancient body, being composed of the ancient Temple of Minerva, the modern front is of the Corinthian order, having a double row of pillars, the body … is the Grecian Doric fluted with bases, they are of great size, the flutes 11” wide straight from edge to edge, not reckoning the curve, the space between pillars has been built up, and forms the side of the church.”

Unusually, we know something of the temple’s original interior splendour from Cicero who, in 70 BC, wrote a description, noting that the doors were originally decorated with gold and ivory and there were interior painted panels depicting Agathokles at the Battle of Himera, 480 BC.

- Left: View of the cathedral in Syracuse, ancient Temple of Minerva by Franz Hegi after L. F. Cassas, 1812-1850 © Rijksmuseum (RP-P-1906-3814),

- Right: Plans of the Minerva temple in Syracuse, by Louis Mayer, 1778 © Rijksmuseum, (RP-T-00-493-77A & RP-T-00-493-77B), all shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

The Fountain of Arethusa

The final stop on their extensive tour of the ancient sites of the city was the fountain of Arethusa, a natural freshwater spring forming a reservoir of open water within the historic core of the island of Ortygia. The spring is associated with the Greek myth of Arethusa and Alpheus; the nymph Arethusa is the patron saint of Syracuse. It is also known for being one of the few places in Europe where papyrus grows. Crompton noted:

“… we went to the fountain of Arethusa, which is a large pool where the general washing takes place for the whole of the town, we saw 30 or 40 women with their petticoats tucked up washing on stones, while the muleteers were coming down in troops to water their mules.”

Fountain of Arethusa, Syracuse, with artists sketching laundry women at work, by W. Wilkins (1778-1839), 1807 © Wellcome Collection (22884i), shared under public domain mark 1.0 universal

Blane observed:

“The celebrated fountain of Arethusa is now confined to a small flow of water in the ditch of the fortification. Instead of nymphs, it was full of dirty washerwomen with their petticoats tucked up in a very singular and unpicturesque manner.”

Crompton and his companions ended their tiring day of sightseeing by visiting the English consul and afterwards wandering around the harbour, looking to find a boat to take them to Malta.

February 18th – ‘nothing of note to book’

This day has one of the shortest entries in Crompton’s journal as he was ill, stayed at the hotel all day and had an early night:

“Not very well and did not go out. In the morning the consul came to call on us and stayed some time, was very civil, helped us to make some bargains with muleteers and boatmen, at length agreed with one to take us to Malta for 20 crowns, and to start tomorrow… This day being in the house nothing of note to book, went to bed early, anything but fit for a journey in an open boat.“

February 19th – southwards to Noto

For their journey 22 miles further south to Noto, to catch a boat to sail to their next destination of Malta, Blane and Crompton parted company. Blane travelled by mule, whilst Crompton took a boat.

Blane recorded the experience in his journal:

“Having agreed with the master of a speronara [boat] to take us to Malta, left Syracuse and proceeded on a mule to the small bay … below the town of Noto where the vessel was hauled up on shore for the purpose of taking in a cargo of oil. Noto is distant from Syracuse 22 miles. Crompton and my cousin the Captain had gone on by sea, but the boatmen afraid of the surf which was rather high owing to the late gale, put in to a small cove 3 miles short of the place where the vessel lay. As I had the passports in my pocket, the guard on the coast would not allow them to quit the beach saying that perhaps being strangers they wished to avoid quarantine. This in no part of the world is so strict as in Sicily. They were in consequence of this detained until I arrived on the mule and we then had to go to the village of Araola and present ourselves to the police… After a great deal of trouble, we succeeded in getting to our vessel after dark. We found it hauled up on shore at Balata in company with one Syracusean and one Maltese speronara. We had to sleep upon the oil casks and were exceedingly uncomfortable.”

Crompton did not sleep on board, but had an equally uncomfortable night in local accommodation:

“… went up to sleep at Noto… after a long and tedious walk we arrived there, and found the accommodation wretched, even worse than what we could have had on board the speronara.“

A Maltese speronara by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-66B), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

February 20th – set sail for Malta

On their final day in Sicily, they set sail from Noto for Malta in the evening after having their Bill of Health drawn up by the police and purchasing a sufficient stock of provisions for their two-day journey.

Epilogue

Staying in Malta until the end of March, Crompton and Blane then travelled onwards through Egypt and Syria, heading for Constantinople (now known as Istanbul). However, there is a sad ending to this tale. After reaching Tarsus (now in south-central Turkey) by the autumn, they both succumbed to a fever, but only Crompton recovered.

William Blane’s death is recorded in The Examiner for the year 1826 (934, Part 87: 222), which reported that he:

“… has been cut off by a violent fever, in his 26th year, on his travels through Egypt and Syria, after a short but brilliant career: he died at Tarsus, on the 7th or 8th October [1825] after three days’ illness.”

There is a gap in Crompton’s journal for this period. However, from a letter he received from a friend in Cairo, dated 31st January 1826 [ZCM], we can gain a glimpse of the wretched time he must have been having, not only due to the loss of his friend and travelling companion, but also having been robbed by pirates:

“I received your letter of Tarsus Nov. 16th with the melancholy news of the death of poor Mr Blane but there is help for it, we all must submit to his will and I am sorrow to hear that you have been ill but thanks to the Almighty you are safely recovered again and I am informed that you have had the misfortune of the loss of all your baggage by the Greek pirates what villainous people they are and I am informed there is no hope of recovering of them again…“

It is extremely fortunate that Crompton’s own travel journal, and the notes made by William Blane of the early part of their journey through Italy and Sicily, survived this terrible ordeal. After Blane’s death, we presume that Crompton took possession of his friend’s writings and kept them safe with his own journal. Their descriptions of the time they spent in Sicily, and the ancient remains they visited, are particularly valuable accounts and make a significant contribution to travel writing of the period.

Crompton returned home to England, and went on to inherit Sion Hill, near Thirsk from his father in 1832, as well as estates at Azerley and Sutton Grange near Ripon in Yorkshire. He was a Liberal MP for Ripon from 1832-1834 and married Mary Alexander in 1834, with whom he had several children.

Further reading:

Ashcroft, M.Y. (ed.) (1994) Letters and Papers of Henrietta Matilda Crompton and her family. Northallerton: North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Bedin, C. (2017) ‘The Neoclassical Grand Tour of Sicily and Goethe’s Italienische Reise’, Studien zur deutschen Sprache und Literatur, 1(37), pp. 31-52. (accessed: 11 January 2024).

Booms, D. & Higgs, P. (2016) Sicily: Culture and Conquest. London: British Museum Press.

Cicero, Second Speech Against Verres in The Verrine Orations, Vol. 1, Book II,

tr. Greenwood, L.H.G. (Loeb Classic Library 221, Harvard, 1928), Sec. LVI, 2.4.124, pp.432-3.

Goethe, J.W. von (1970) Italian Journey. London: Penguin Books.

Holloway, R.R. (2000) The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge.

Jannelli, L. & Longo, F. (2004) The Greeks in Sicily. Verona: Arsenale EBC.

Treuherz, J. (2023) Art and Architecture of Sicily. London: Lund Humphries.

Acknowledgements

The two parts of this article developed out of a short essay written in December 2023 on Joshua S. Crompton’s visit to Syracuse for the Oxford University Department of Continuing Education online short course: Sicily’s Art and Architecture: From Magna Graecia to Stupor Mundi, led by Dr Philippa Joseph. I am particularly grateful to Dr Joseph for her support and encouragement, and for drawing my attention to Goethe’s dismissal of Syracuse.