By Gail Falkingham, Record Assistant

This blog is the first in a two-part series exploring the journals of Joshua Samuel Crompton (1799-1881) and William Blane (1800-1825), which describe their journey through Sicily between the 8th and 19th February 1825 en route from London to Malta [ZCM]. Part one covers the initial stage of their journey to Sicily by sea from Naples on the west coast of Italy, to Messina on the north-east coast of Sicily, and thence southwards down the east coast to Catania via Taormina, describing the Greek and Roman remains they visited. Part two covers the southernmost leg of their journey, picking up their itinerary in Nicolosi from where they climbed Mount Etna and then travelled further south to Syracuse to see the ancient sites, before setting sail for Malta.

A note on the illustrations: these travel journals contain text only, extracts from which are cited below. To illustrate the ancient sites they describe, images of late-18th-century paintings and drawings have been reproduced under licence from a number of public collections to whom we are most grateful.

Sicily in the long eighteenth century

“To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is not to have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything”.

J.W. von Goethe, Italian Journey, 13 April 1787

Contrary to the above quotation from Goethe, who travelled through Italy and Sicily in 1787, for most of the 18th century, Sicily was considered a remote and unknown island visited by relatively few tourists. Its popularity grew in the latter part of the century following the publication of several guidebooks and travel journals, which raised awareness of the well-preserved remains of ancient Greek civilisation on the island. The intellectual and scientific curiosity of the Enlightenment, new archaeological discoveries and the neoclassical ideas of art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann encouraged a growing interest in, and admiration for, Greek art and architecture. This, it was realised, was an earlier and thus purer form of art than the later Roman art and architecture it had influenced.

Temple at Segesta, Sicily by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-T-00-494-61), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

Scholars, writers, artists and architects were drawn to the former areas of Greek settlement in southern Italy and Sicily, known as Magna Graecia, to visit the ancient sites. Here, they were more accessible than those in mainland Greece itself, which was at that time part of the Ottoman Empire. Sicily preserves some of the oldest and most complete Greek temples of the ancient world, dating from the seventh to fifth centuries BC, as well as numerous Roman sites from its time as a Roman province following the Punic Wars with Carthage in the third century BC.

The sea crossing to Sicily from Naples or Rome was a journey that could take several days, depending upon wind and weather conditions and the type of sailing vessel. In the 19th century, steam ships made the journey quicker and less dangerous than by sail. Once there, travel over land was difficult, slow and uncomfortable due to the poor condition of the roads, many of which were suitable only for mules rather than carriages, so travellers had to ride or walk on foot. There were also threats from brigands and wild animals. Outside of the main towns, accommodation was limited and there were relatively few inns and places to obtain food and refreshment.

Nevertheless, travellers would endure these discomforts, not only to visit the ancient sites, but also to see the other attractions of the island such as the volcanic activity of Mount Etna, the opera, religious festivals and firework displays.

The crater of Mount Etna by Willem Carel Dierkens, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-64), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

Notable later-18th-century travellers to Sicily include Goethe, the German writer and poet, who visited in 1787 and published his Italian Journey in 1816. A few years before, in 1810, Goethe had also published the travel diary of artist Richard Payne Knight, who visited Sicily a decade before him in 1777 and wrote about the ancient sites he saw. Antiquarian Sir Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead’s account of his travels through Italy and Sicily in 1789-1790 appeared as his Classical Tour in 1819. We know that Joshua was familiar with this work as he records in his journal on 24th February 1825 whilst in Malta:

“Dr Wilson this morning having been so kind as to offer me his library, I took Sir Colt Hoare’s Travels in Sicily, and Malta, and found them as far as I have seen the country very accurate.”

Joshua Samuel Crompton (1799-1881)

One of nine children, Joshua Samuel Crompton was born into a wealthy Derbyshire banking family, who developed their business in Yorkshire and owned Esholt Hall, near Bradford as well as property in York and the North Riding. Joshua had a classical education, studying at Harrow and Cambridge, and was familiar with the writings of Homer and Cicero. He inherited Sion Hill, near Thirsk from his father in 1832, as well as estates at Azerley and Sutton Grange near Ripon. He was a Liberal MP for Ripon from 1832-1834, and married Mary Alexander in 1834.

His elder brother, William Rookes Crompton, had travelled in Italy before him, visiting Rome and Naples, from where he wrote to their sister Henrietta Matilda in early March 1818: “… I know not whether I shall afford to see Sicily, Greece I am afraid which I most long to see is out of the question…” From his later correspondence, we know that Rookes travelled south to visit the Greek temples at Paestum, and was back in Rome by mid-April 1818, but we have no record of him having visited Sicily.

Joshua Samuel Crompton’s travel journal

At the age of 26, in December 1824, Joshua set out from London for what was to be an almost year-long trip through France and Italy, to Sicily and Malta, through Egypt and Syria and on to Constantinople (now Istanbul in Turkey). For part of the journey, he was accompanied by William Blane (1800-1825) of Winkfield, Berkshire, and Blane’s cousin, referred to in the journals as ‘Captain’.

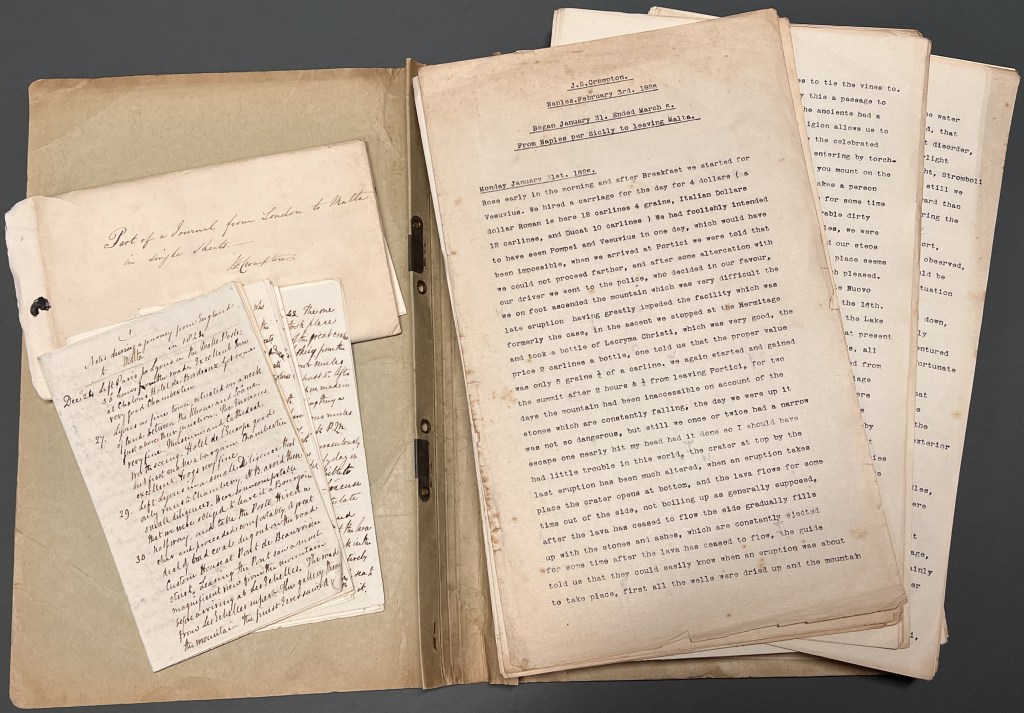

ZCM Typescript of the travel journal of Joshua Samuel Crompton ‘from Naples per Sicily to leaving Malta, 31 Jan to end Mar 1825’, with handwritten diary pages of William Blane from ‘part of a journal from London to Malta in single sheets‘

The collection of Azerley Chase Records in the custody of the Record Office [ZCM] contains a typescript of Joshua’s travel journal and other handwritten notes made by William Blane. They are arranged chronologically, providing daily accounts of where they went, stayed, how they travelled, what they saw, ate, and who they met.

Leaving Naples by sea for the port of Messina on 8th February 1825, they arrived in Sicily two days later. The three men spent nine days travelling south down the east coast of the island, to Taormina, Catania and Syracuse visiting ancient sites and museum collections as well as climbing Mount Etna en route. They did not, however, journey further westwards to Palermo, or to see the Greek temple sites at Agrigento, Selinunte or Segesta; this would have taken them several more weeks to do so. Their travels through Sicily ended on 20th February, when they sailed from Noto for Malta in a speronara boat.

Satellite view of Sicily showing its position relative to Naples and Malta and the east coast towns visited by Crompton. Imagery © 2023 TerraMetrics, map data © 2023 Google.

February 8th 1825 – by sea from Naples to Messina

Their journey from Naples to Sicily started badly as they were detained by custom house officials and, unfortunately, missed the steam boat they had intended to board, which they were unable to flag down once it had set sail:

“…we were much hindered, and when we arrived at the port we found that it was past ten, we put all our luggage and selves in two boats and rowed out as quick as possible, as we saw that the Boat was already waiting off the pier, but by the Custom House offices we were again detained, and what was our mortification when we found when we had cleared the port, that the steam vessel had already started, and was more than half a mile out at sea, the number of boats full of all persons could not allow them to distinguish the handkerchiefs which we waved, as a signal for them to lay to, which they would have done if they had seen it, as 3 passengers 27 ducats each make a material difference to the trip.”

They returned to the harbour and were fortunate to find a merchant ship, the ‘William of Liverpool’, willing to take them that day as passengers to Messina.

“I say at half past 12 we left the harbour, and at 10 past one left the anchorage just outside, we had a lovely day and a beautiful breeze, and the surrounding country looked lovely!”

Three ships: two spéronares of Scilla and a tartanes, Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-35A), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

However, the merchant ship had limited accommodation and their passage was not uneventful, Crompton wrote of it:

“Mr Blane was sick from the first, and Captain felt very squeamish, so that I was the only one who did not suffer. When night came on as there were only two berths and they were in them sick, I found a bed on the boards close to the Rudder, and covering myself with my coat and cloak fell fast asleep. The breeze kept increasing, and about 12 at night we were obliged to take nearly all our sails, as when we were passing off the celebrated Promontary of Palinurus we had a tremendous breeze.“

They sailed past the Lipari Islands, Stromboli and the island of Capri, the latter of which:

“…as seen from our vessel did not seem that enchanted spot which we had been led to suppose it was by the description of the ancients, and by its being the scene of the luxury and debauch of the Roman Emperors. Nevertheless the exterior is very fine.”

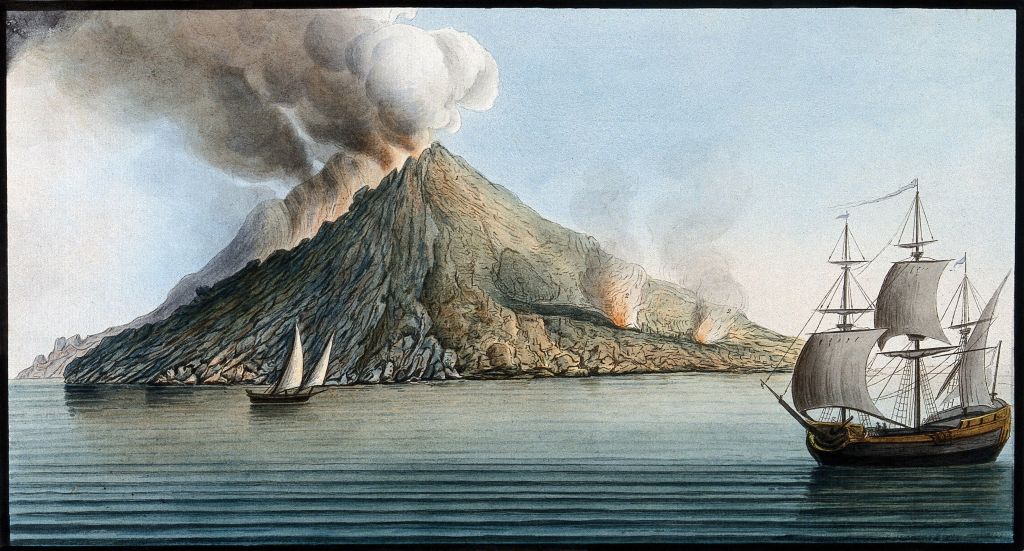

The volcanic activity of Stromboli, however, was of greater interest:

“Stromboli never ceases to vomit, at the time we passed it it was busy smoking and during the night of the 9th constantly we saw the red top of the mountain blazing in a beautiful manner, the reflection on the sea, particularly as it was much agitated, was fine, and of course to me novel as also to the whole of our crew, who were entirely guided by charts having never been in the Mediterranean before.”

The island of Stromboli, smoke erupting from its peak by Pietro Fabris (fl.1756-1784), 1776 © Wellcome Collection (43676i), shared under a public domain mark 1.0 universal licence

February 9th – adrift at sea

A brisk wind blew their ship off course, further west of their original route. Once the wind dropped, they drifted back and forth and did not pick up speed again until the evening, after which the wind blew all night. Crompton wrote:

“I to avoid the wet, went into the hold, and made a tolerable bed on some sails, the wind during the night was violent … the rocking of the vessel, discomposed my two companions wonderfully, during the night Stromboli was very beautiful, constantly sending forth fire, and smoke, which in the night looked beautiful, when daylight appeared the morning looked very promising and for a short time we had rather a brisk and favourable wind, but about 8 this again dropped and we were drifting about on all sides, on account of the currents, the islands form them in every direction.”

February 10th – arrival at the port of Messina

View of the port of Messina and the mountains of Calabria from the quay, Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-18A), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

Having had a long and tiring journey, they finally arrived in Sicily at the port of Messina, but faced more delays before going to their hotel, spending the evening at the opera and having an early night:

“Arrived at Messina at about 12 in the afternoon but could not go on shore as we, coming in a merchant vessel, could not land till we had been at the health office and that was not open, as from 12 till two in all parts of Italy all public places are shut, even the post-office, that is the time allowed for persons to take their siesta. When that time had expired we all repaired to the office, our Passports were well smoked in a fire, and examined, and after a little trouble we were allowed to enter the Town, Mr. Power the merchant our Captain was to meet, was particularly kind, he shewed us the Inn, we went to the Gran Bretagne, and found it very comfortable, a clean House, and not exorbitant in its charges. Went out to look at the town, but as it was soon dark could see but little, went to the opera, ‘Barbiere di Siviglia’, went to bed early.”

ZCM Passport of Joshua Samuel Crompton issued in London, 14 Dec 1824, written in French

February 11th – by mule en route to Catania via Taormina

To reach Catania, 60 miles away to the south, they faced a long and tiring two-day journey by mule, resting overnight at Il Gardino, near Taormina:

“Rose very early and having bargained with a muleteer for the animals that were to carry ourselves, and luggage started for Catania early. We were to pay for each mule 30 taris, a Tari = a carline, 12 to a crown, 10 to a Ducat. We had 2 for our luggage, and 3 for selves, to go to Catania in 2 days, distance 60 miles…”

Ancient ruins near Messina, Sicily by Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond, 1842 © National Gallery of Art, Washington (2004.166.32), shared under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) licence

There are several detailed descriptions in Crompton’s journal of the local landscape, including a lengthy discussion about the prickly pear cactus, an example of which can be seen in the painting above. Frequent references are also made to the poor quality of the roads:

“… indeed the roads are now so bad, that though the one to Catania is considered one of the best in the Island, yet it is the most miserable mountain track that never was passed over, it is called the Rejia Strada.”

“Arrived at Il Gardino, a small place on the seashore, just under Taormina, where we slept…went as early to bed as possible, all the Party a good deal tired.”

February 12th – visiting the ancient sites of Taormina before breakfast, then on to Catania

Before re-commencing their journey to Catania, Crompton and his party rose early for a guided tour of the ancient sites of Taormina. The Greek settlement of Tauromenion was founded in the 4th century BC and preserves the remains of the second largest Greek theatre in Sicily, cut into the hillside overlooking the sea. This theatre was later extended by the Romans, who built a number of other monuments, including a smaller theatre, or ‘odeon’.

Crompton described the sites they visited:

“Started early for to mount the hill, on which the modern town of Taormina stands, two or three of us procured donkeys, the rest walked, the ascent is by a winding path as bad and miserable as any person can imagine, after about 3 quarters of an hour’s steep ascent you enter the town, our guide who presented himself in full costume having heard of our intention overnight, now began to give free scope to his tongue, much information he gave us, some of course exaggerated… “

Exterior facade of the Taormina theatre at the level of the stage on the sea coast, by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-46), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

“… the 1st ruin was the theatre, a most splendid remain, the form quite perfect it is the largest in the world, its size seems to give you the idea of the impossibility of any person situated at a distance from the stage to hear any part of the performance, this we told to the guide, who desired us to mount the farthest part while he stood on the stage and recited something, this was done in good style, a compliment to strangers English, and we distinctly heard every word, notwithstanding its ruined state, we fired a gun from the stage but it produced no effect.”

Blane wrote of the theatre of Taormina:

“Taormina the ancient Tauromenium is built on the side of the mountains overlooking the sea and commands a magnificent view of Etna. The ruins of the theatre are very fine and perfect, a great part of the Scena being still remaining erect. What a strange passion all the ancient Greeks and the Romans their imitators, appear to have had for theatrical representations. To have built so large a theatre would seem to prove that Taormina was once a very populous city; yet its situation decries this.”

The Greek theatre at Taormina with a view of Mount Etna by Jean-Pierre Houël, c.1776-1779, via Wikipedia Commons, public domain

Crompton said of the view from the hill of Taormina:

“The view from here is quite beautiful, looking over the country we passed through yesterday, and in the opposite direction the fine, bold, strong regions of Mt. Etna quite enchanted, and astonished us, Etna from here, on account of the great size of its base, and its innumerable craters on all sides, loses much of its height, but the nearer you approach it the more majestic its summit appears, the very top is quite bare of snow on account of the great quantity of smoke every moment issuing from the crater…”

From the theatre, they went to see the ancient reservoir and the Naumachia (a large, monumental brick wall built in the 2nd century BC incorrectly thought to have been part of an amphitheatre where reconstructions of naval battles were held). They then returned for breakfast, after which they rode south for two or three miles heading towards Catania:

“… You now come on the territory of Etna, everything is volcanic, the walls composed of lava, and scoria, the ground torn and rent in every fantastic form, and every here, and there, a younger stream of lava carries destruction with it till its progress is arrested by the sea…”

From Taormina to Catania is a distance of 33 miles, a journey which takes under an hour by car nowadays. By mule, with breaks en route for rest and refreshment, it took them the rest of the day. On arrival Crompton wrote:

“ The entrance into Catania was rather favourable, as it was the grand festival of Santa Agata, who is the Lady patroness of the town, in the grand square before we left our mules, we saw the fireworks, which were lighted on the return of the people from the Cathedral, which is situated in the same place, they were well-managed and seemed to excite great admiration; we stopped at the Elephant, an hotel kept by an old Etna guide, he speaks good English, and is as yet very civil, he has numerous recommendations from persons who have been in his house, he has mounted the crater 394 times, and told us of the practicability of the undertaking, which all others before doubted.”

The annual Festival of Sant’Agata, the patron saint of Catania, is one which still takes place every February.

February 13th – a morning visiting the archaeological sites and museum in Catania, then on to Nicolosi

Despite being advised by locals of the madness of their intent to climb Mount Etna, they arranged for mules to take them that afternoon to Nicolosi, twelve miles to the north-west of Catania in preparation for their ascent of the smoking volcano the following day:

“This morning, we engaged mules to ascend Etna, we were to start early in the afternoon about 2, and got to a small village called Nicoloso where we were to sleep, and early the next day mount the Crater… a person who was so kind as to show us the Antiquities told us of the perfect impossibility of the undertaking, that at this season of the year such a step would be madness. Even where we were going to sleep, it would be so cold, as to make us perfectly miserable, but as we determined to make the attempt we settled our plans for so doing. In the meantime we went to see some of the splendid remains of this celebrated city…

They spent the morning in Catania on a tour of the archaeological remains before visiting the museum collection of Ignazio Paternò-Castello, 5th Prince of Biscari.

Exterior view of the old small theatre, or Odeon in Catania by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-51), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

“… The whole of this city has been destroyed perfectly 6 times, 4 by earthquakes, and 2 by lava, in the first place which we went to see, which was the theatre for actors, and the Odeon the theatre for music, we saw quite sufficient to justify these reports, even this ancient and celebrated theatre, much older than any in Rome, is built on the remains of another ruin, which from the recent excavations shew it to have been a very fine edifice, the stones are hewn quite square, they are lava and made to fit without mortar, on this as I said before the ancient theatre and Odeon stand, these are now quite covered with lava, and ashes, many yards deep, this was occasioned by the eruption from Monte Rosso, which destroyed the whole city, greatly altering the shape of the harbour, as it drove back the sea some distance, the date 1699, we were much delighted with this ruin. From being covered, and only passing through the arched excavations by torchlight, we had not the same perfect view as at Taormina, only having seen that perfect we had a good idea of this, all the Grecian theatres being after the same plan.“

A view of the harbour at Catania by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-50), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

“From this place we went to the museum, which is an assemblage of all the curiosities of the neighbourhood, ancient armour, statues, natural curiosities, Roman and Egyptian remains, and many other things which occupy a large space, 7 or 8 rooms. If I may venture to give an opinion they have no celebrated statue, they seem all to be copies of the ancient statues themselves, as Apollo Belvedere, Venus, Hercules etc. the collection of ancient weapons perhaps the best worth observation.“

These artefacts now form part of the collections of the Ursino Castle Civic Museum in Catania.

“From this place we went to the excavations of the ancient Warm Baths, which are situated near the sea, they are fine remains, formerly they were cased with marble of a very large grain, an inch thick, this by the lava flowing in has nearly been all destroyed, leaving only the brick, and lava, of which the arches were formed. From here to the excavation of the ancient wall, this certainly pleased me as much, if not more, than anything I had yet seen.”

Basement of the amphitheatre of Catania by Louis Ducros, 1778 © Rijksmuseum (RP-T-00-493-52), shared under a public domain (CC0 1.0) licence

They then went to see the cold bath, and the amphitheatre, “which must have been an immense building if we may judge from the part at present discovered… and you are enabled only by torchlight only to see a small part at once…”

“All these excavations were made by Ignazius Paternus, Prince of Biscari, who at his own expense made all these great additions to the curiosity of the travellers who visit Sicily, he wrote a description of the island, and also one of Malta, which perhaps is the very best guide you can procure for this country, we found it very useful, the descriptions tolerably correct, and not exaggerated by Ignazio Paternò, Principe di Biscari.”

Crompton included advice on a few items he considered necessary when travelling through Sicily:

“Having viewed all these antiquities, we returned to our inn to get dinner and prepare for our Etnean trip, we did so, taking provisions, and a change of clothing, also a kettle and some tea, this I would recommend to all travellers, as glasses are always to be procured, and eggs for the substitute of cream, which when well beaten form capital cream. The kettle is the pot and kettle, and makes a good beverage, sugar, and tea are the only requisites to be taken with you, at Palermo or Messina you procure these, which you may carry round the Island, as the ware you get in travelling is execrable, and if you manage to procure rum, which is the only spirit, and that very difficult to procure, when you have obtained your object that is bad in quality. Tea, sugar, and if possible a small canteen I strongly recommend to all travellers in Sicily. Your baggage mules will take a quantity of luggage, and this is the most necessary part, to persons who are affected by sour bread, biscuits are mighty desirable, and you get good ones at Naples, (and I should also imagine at Palermo, and Messina).”

Crompton described their afternoon journey to Nicolosi as:

“… a most delightful ride of 3 hours’… Soon after we arrived there it became dark, so we only took a short walk, and returned to our inn, which though miserable, was clean and the host obliging. We had tea and went to bed, previously having engaged guides, and settled we were to be called at three in the morning.”

Part two to follow…

Part two of this blog, to follow, will pick up our travellers’ journey on 14th February 1825 from Nicolosi to Mount Etna. Their ascent of Mount Etna will be covered, as will their journey further south to the city of Syracuse and the ancient sites they saw there, before sailing for Malta on 20th February.

Further reading:

Ashcroft, M.Y. (ed.) (1994) Letters and Papers of Henrietta Matilda Crompton and her family. Northallerton: North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Bedin, C. (2017) ‘The Neoclassical Grand Tour of Sicily and Goethe’s Italienische Reise’, Studien zur deutschen Sprache und Literatur, 1(37), pp. 31-52. (accessed: 11 January 2024).

Black, J. (2003) The British Abroad: The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Limited.

Booms, D. & Higgs, P. (2016) Sicily: Culture and Conquest. London: British Museum Press.

Chaney, E. (1998) The Evolution of the Grand Tour. London: Frank Cass.

Goethe, J.W. Von (1970) Italian Journey. London: Penguin Books.

Holloway, R.R. (2000) The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge.

Paternò, I. (1781) Viaggio per tutte le antichita della Sicilia. Naples. (accessed: 11 January 2024).

Retzleff, G. (1989) ‘The British Discovery of Sicily: Western Greeks and Liberty’, Man and Nature, 8, pp.119–128. (accessed: 11 January 2024).

Stumpf, C. (ed.) (1986) Richard Payne Knight: Expedition into Sicily. London: British Museum Publications.

Treuherz, J. (2023) Art and Architecture of Sicily. London: Lund Humphries.

What a wonderful blog. Clearly, it is the result of detailed research, and is beautifully presented, with well sourced, contemporary images. This work also brings alive the physicality and perils of travel in the late eighteenth century, as well as the awe and wonder of discovering the ancient sites of Magna Graecia. While the travels of Goethe are well documented, those of Crompton have hitherto not been widely known – until now, that is – this is a great addition to scholarship in the field. I look forward with great interest to viewing the second instalment.