By Jo Faulkner, Record Assistant

‘Applying hair powder, circa 1750’: (Wellcome L0006483.jpg) licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence

The expression ‘big wig’ to describe a person of high status and wealth originated in the 18th century when it was fashionable for noblemen and noblewomen to wear large wigs, to signify their wealth or status in society. This fashion seems to have originated in France in the 17th century, where Louis XIII used wigs to cover his thinning hair. Wigs were very expensive to acquire and maintain. The practice of powdering the hair began to appear in England in the 17th century. Expensive wigs were crafted from human hair, though more often they were made from horse or goat hair. Those made from animal hair were hard to keep clean, had an unpleasant odour and attracted lice. Powders to apply to wigs were made from ground starch combined scented essences such as lavender or orange. The powder would be applied after a lotion or pomade, using small bellows.

Wigs were a major status symbol during the 18th century, but by 1800, they had fallen out of fashion and were replaced by natural hair.

The demise of the wig was partly connected to the introduction of an Act. During the late 18th century, all kinds of taxes were introduced to finance government programmes and crucially wars with France. They included tax on carriages, servants, windows, horses and coats of arms. The Duty on Hair Powder Act 1795 (35 Geo. III, c.49) levied a tax on hair powder.

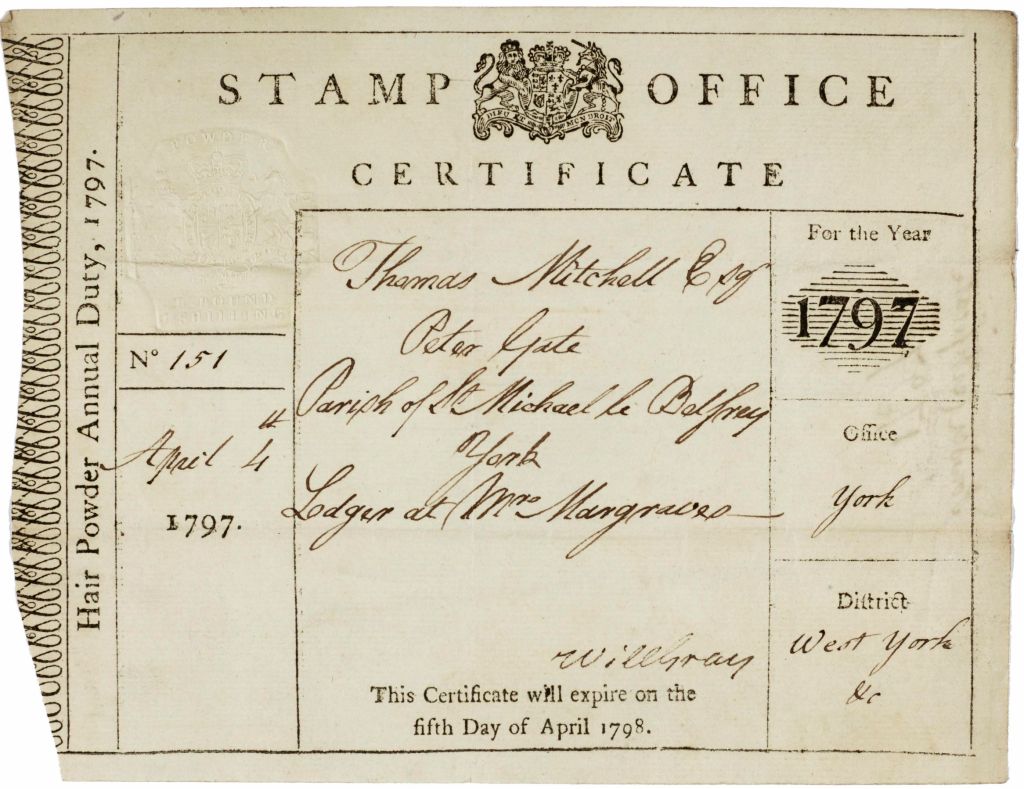

Those who used hair or wig powder were required to buy a certificate from the local Justice of the Peace at a cost of one guinea. The list of those that had paid was lodged with the local court of Quarter Sessions and a copy was displayed on the door of the parish church.

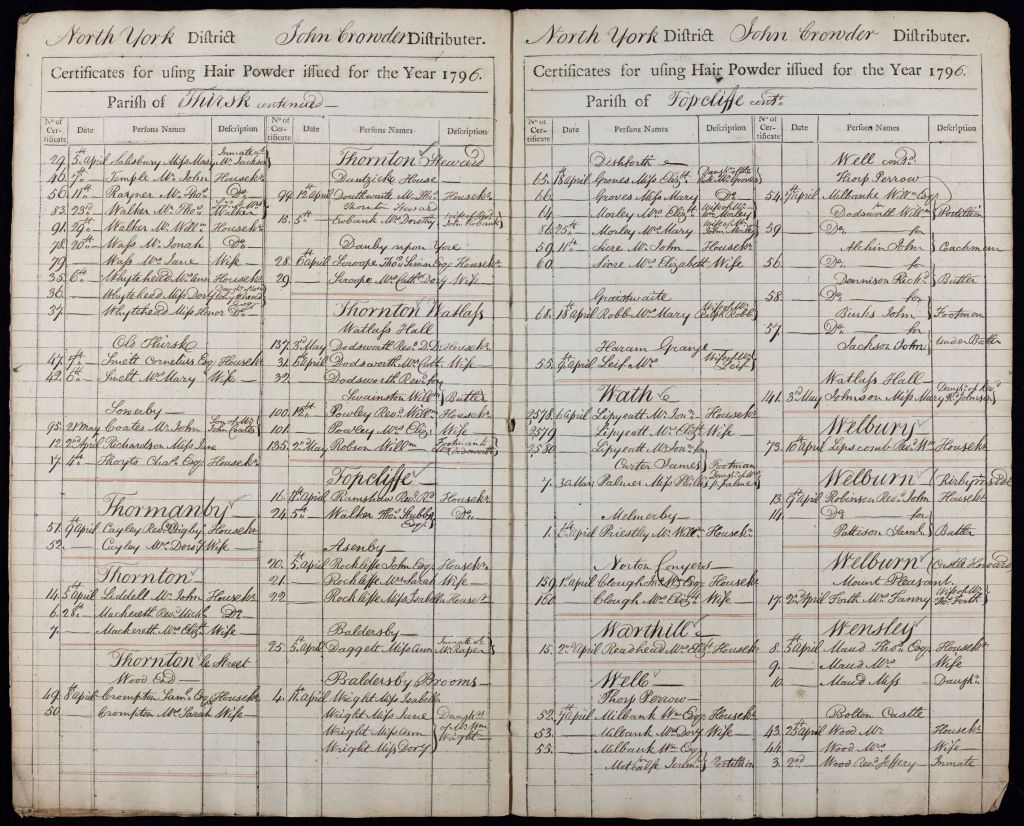

The information recorded in the register of hair powder certificates includes the date, parish and a list of names with a description such as the relationship to the head of the household or another role such as servant. These records can be useful in researching people who lived in the Georgian era, when parish records can sometimes offer limited details and a compete census had not yet been undertaken. The lists are obviously, limited in their use because most people were not of a status to wear wigs and use hair powder. There were also exemptions to the tax, such as most clergymen, non-commissioned officers, militia, mariners and low-ranking naval officers. A group of servants in one household was covered by one payment.

QDH register of hair powder tax certificates for Thirsk, 1796

Those who chose to pay the guinea hair powder tax, were nicknamed ‘guinea pigs’ by reformist Whigs who favoured very short hair. Their statement ‘French cut’ represented political allegiances and a solidarity with the French. Those who favoured this modern cut were satirized in the press as members of the ‘crop club’.

If you think your ancestor, or someone you are researching may have been a ‘big wig’ or ‘guinea pig’, it may be worth looking into registers of hair powder certificates. A register of hair powder certificates 1795-1797 (reference QDH) is available on microfilm at the North Yorkshire County Record Office. Occasionally some of the large family and estate collections contain related records, such as certificates for the payment of this duty.

As a footnote, it is interesting to consider that the demise in the fashion of the wig may not have been entirely due to the hair powder tax. Both baldness and wigs appear to have been subjects of some humour at beginning of the 19th century. This comedy was often politically motivated and satirical in nature, though sometimes more whimsical.

A verse in the hand of the Honourable Reverend Thomas Monson of Bedale (1764-1843), which seems to be based on a Scottish song ‘Shepherds I have Lost My Love’, provides a rare glimpse into the humour of a wealthy clergyman:

Shepherds I have lost my wig

Have you seen my caxon

Of auburn bright & not too big

To supersede my flaxen.

Tis true I saw it on the head

Of many a drunken varlet

Of Bob & Dick & Tom & Ned

& some turn’d up with Scarlet.

Oh! save me from the Quaffing tribe

& hide my head so bare

Not Wales nor Kendrie can supply

Another quite so fair.

ZBA 22/1/313 verse in the hand of Reverend Thomas Monson

References and further reading

Header images: North Yorkshire County Record Office ZBO IX 1/3, sketchbooks of Thomas Orde-Powlett

Dowell, Stephen (1888), A History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Year 1885. Volume III. Direct Taxes and Stamp Duties. London: Longmans, Green & Co

Festa, Lynne (Harvard University), Wigs and Possessive Individualism in the Long Eighteenth Century

Thanks you so very interesting