By Gail Falkingham, Record Assistant

Part 1 of this blog contained an overview of the Copperthwaite papers, with Part 2 looking at the notebook and plans kept by Copperthwaite and the archaeological information on the Prehistoric finds. This post will focus on the Roman discoveries within the collection, selecting examples from the contents of the notebook and plans.

The Illustrated Notebook

One of the notebooks contains a number of sketches of artefacts, mainly Roman in date, but also some prehistoric and some medieval, from Malton, Norton and surrounding areas [ZUN 2]. These illustrations include pottery, items of jewellery, inscriptions and there are descriptions of over 200 coins.

Roman discoveries

The majority of the finds illustrated in the Copperthwaite notebook date from the Roman period, during the first four centuries AD. There are a number of drawings of different types and forms of pottery, including an amphora, mortarium, jugs and bowls. Some are complete vessels, others broken sherds; several drawings of the latter are of decorated samian ware. Also known as terra sigillata (‘clay bearing little images’), this type of pottery was mass produced in Gaul (France) and Germany for the Roman provinces and is commonly found on Roman sites. It was made in moulds to produce relief decoration, usually in a classical style, and then covered in a fine, glossy orange red clay slip. It was made in a wide variety of forms and exported to Roman Britain from the mid 1st to mid 3rd century AD. Used as fine table ware, it was the Roman equivalent of our modern day Wedgwood dinner service.

Image courtesy of York Museums Trust :: https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk :: CC BY-SA 4.0

Another, far more unusual, pottery item is this head- or face pot, which was

“Found at Norton in 1822, made of bluish clay. Appears to have been the head or upper portion of a pitcher, representing Roma. Some small coins much decayed were found with it”.

It is drawn at its exact size, 10cm tall and a similar width across the top. The specific use of these pots is uncertain. Examples have been found containing cremation burials, others may have been used for storage, or for wine. This Norton pot appears to have been broken off at its base; there is, however, no mention of it containing the remains of a cremation burial, although there were coins. Its current whereabouts are unknown, and it will be interesting to see if it can be located within the collections of one of our local museums.

Images courtesy of York Museums Trust :: https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk :: CC BY-SA 4.0

Cremation urns fashioned into a human head, or face, were a particular tradition of the later 3rd and 4th centuries AD in Yorkshire. Examples can be seen on display in the Yorkshire Museum and two similar pots from the collections are illustrated here. One, although in a more fragmentary condition, and made of a different clay fabric and depicting a male face, shows a comparable vessel form in profile and is a similar size and shape to the Norton example. A second, complete example is shown face on, depicting a male head and face, with hair and beard.

Another wonderful drawing records the location of a crouched human burial found during excavations for a new wing of the workhouse in September 1848. We know from historic maps and plans that the Malton Union Workhouse was located off Sheepfoot Hill, at the bottom of Orchard Field. It was one of the laws of ancient Rome that burial should not take place within the city. As a result, the vast majority of people were buried outside the settlements in which they lived, commonly grouped along the roads leading from them. We know that there was a Roman road leading down from the south gate of the fort to the River Derwent, which passed through this area of burials.

The notes indicate that the skeleton was found beneath a floor of cement and small broken brick, close to a bronze coin of the Emperor Trajan (an X marks the spot). Also depicted is a “curious cyst full of burnt ashes, covered with stones having somewhat the arrangement of rude arching.”

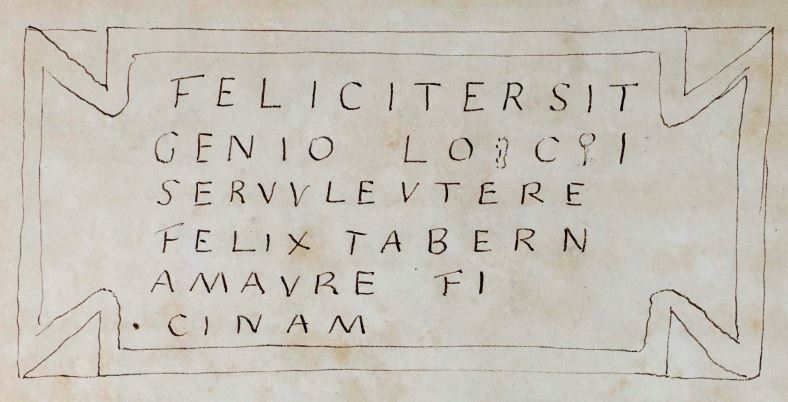

Three Latin inscriptions are recorded in the notebook, all of which are known from other sources and recorded in the Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB) catalogue. The two smaller illustrations are a tombstone (RIB 714) found in 1753 in the Pye Pits (bottom left), the whereabouts of which was unknown even in the mid 19th century. The other, (bottom right) is a dedication to the god Mars Rigas (RIB 711), and is held by Malton Museum, which also has a replica of the larger inscription (RIB 712), which is a dedication stone for a goldsmith’s shop. This is the only one of its kind so far discovered in Roman Britain and dates to the late 3rd to early 4th century (c. AD 275-325).

(Photo: Gail Falkingham)

The notebook records that “this inscribed stone was found at Norton when the Old Church Yard wall was being renewed”. The translation of the inscription reads: “Good luck to the genius of this place! Good luck to you, young slave, in running this goldsmith’s shop”. The original dedication stone is on display in the Yorkshire Museum, York. Its museum label notes that “the slave must have been in a position of authority to be referred to specifically. It seems he was better cared for and better off than many free citizens working in Roman Britain”. In Roman mythology, the genius loci is the protective spirit of a place, and is often mentioned in Roman dedications.

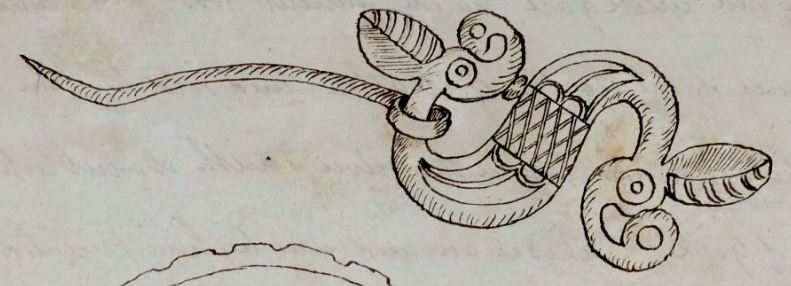

The facing page to the inscriptions contains drawings of a number of items of jewellery. These include a distinctive, dragonesque brooch (looking like a dragon), of the later 1st century AD. This is one of a relatively small group known from Roman Britain. Copperthwaite describes the discovery of the brooch at Norton in 1844 in digging the foundations of Williamson’s Cottages. It was found along with a quantity of human bone, at a few feet distance from the rings of jet and brass (which are also illustrated).

This ‘S’-shaped brooch type (Hull Type 200), is found mainly in the North of England where they are presumed to have been made as a native product. Usually made from copper alloy (bronze or gunmetal), each end (terminal) of the brooch represents a head, with a sunken, circular eye, large ears and a snout (Bayley and Butcher 2004, 171; 259). The brooch pin, shown here extended out to the left, is attached around one neck, and would have swung round the back to fasten to a catch behind the other. The central plate displays a band of diamond-shaped cells between semi-circular and curvilinear cells of enamelled decoration, Copperthwaite records that “this brooch is enamelled with a yellow and blue vitreous paste”.

Similar examples of this type of brooch can be found in the collections of the Yorkshire Museum, York. Originally, the metal would have been bright and shiny, as would the coloured enamel decoration. The metal has corroded and the enamel has faded over the centuries, but you can still make out the blue and yellow enamel, and tiny areas of red.

Images courtesy of York Museums Trust :: https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk :: CC BY-SA 4.0

Towards the end of the notebook, there are several pages recording the details of over 200 Roman coins. The names of the Roman emperors who issued the coins are listed, along with the Latin inscriptions around the edge. There are descriptions of the images on the obverse and reverse (front and back) and notes on whether the coins are made of gold, silver or bronze. This is surely of interest to numismatists (coin specialists) and may assist in the identification of coins in local museum collections and provide evidence of their provenance.

As can be seen from the examples described above, the Copperthwaite notebook contains a wealth of interesting archaeological information. I hope that publicising this collection of material in these blog posts will raise awareness of its existence, stimulating interest in, and discussion about, the contents, as well as promoting further research which will help us to better understand the history and archaeology of the town of Malton and surrounding area.

Next time in The Papers of William Charles Copperthwaite Part 4 we will focus on the medieval and later content within the Copperthwaite papers.

To find out more

The Yorkshire Museum, York and its online collections

Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB)

Further reading

‘Roman Brooches in Britain: A Technological and Typological Study based on the Richborough Collection’ by J Bayley & S Butcher, 2004. London: The Society of Antiquaries of London.

‘Romano-British Face Pots and Head Pots’ by G Braithwaite, 1984, in Britannia, Vol. 15, pp.99-131. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

‘Roman Yorkshire, People, Culture and Landscape’ by Patrick Ottaway, 2013. Pickering: Blackthorn Press.

Very interesting. Thanks for posting.

The vessel spout is similar to others from York in the Yorkshire Museum collections. They are late Roman but the Malton one is hard to date without seeing it. I think it probably represents an empress wearing a diadem, probably studded with pearls. A diadem would not usually have been worn by other women.