by Gwyneth Endersby, Record Assistant

Summary

As part of our celebration of 75 years of the archive service in North Yorkshire, we have been highlighting different aspects of the collections in our care. This blog explores the range of Medieval documents we hold, taking a closer look at three especially notable examples.

Introduction

Manuscripts from the Middle Ages (AD475-AD1500) here at North Yorkshire Archives date from the first half of the 12th-century. Potentially, earlier deeds might exist, as not all documents are datable in a way we would recognise today. It was common, for instance, to date Medieval deeds according to a day of the week or nearest religious feast day, plus the year of a reigning monarch.

- Left: West Heslerton deed (No. 1), c.1165, and possibly earlier, from the Fairfax of Gilling archive [ZDV(F)]. It is believed to be the oldest datable deed held at North Yorkshire Archives.

- Right: Grant by Robert de Bruce, Lord of Annandale, to John of Romanby of a salt marsh at Hart, County Durham with pasture for two horses in the warren there, c.1270-1290. From the Mauleverer of Ingleby Arncliffe archive [ZFL 48]

Most Medieval manuscripts we hold are charters, granting land or privileges, and many retain their detailed wax pendant seals which were used to authenticate legal documents from the late-11th century to the end of the Middle Ages.

Other examples of Medieval documents include legal agreements (such as marriage settlements), personal official documents (such as wills and testaments within family archives), manor court rolls or books, account rolls, and royal and ecclesiastical documents.

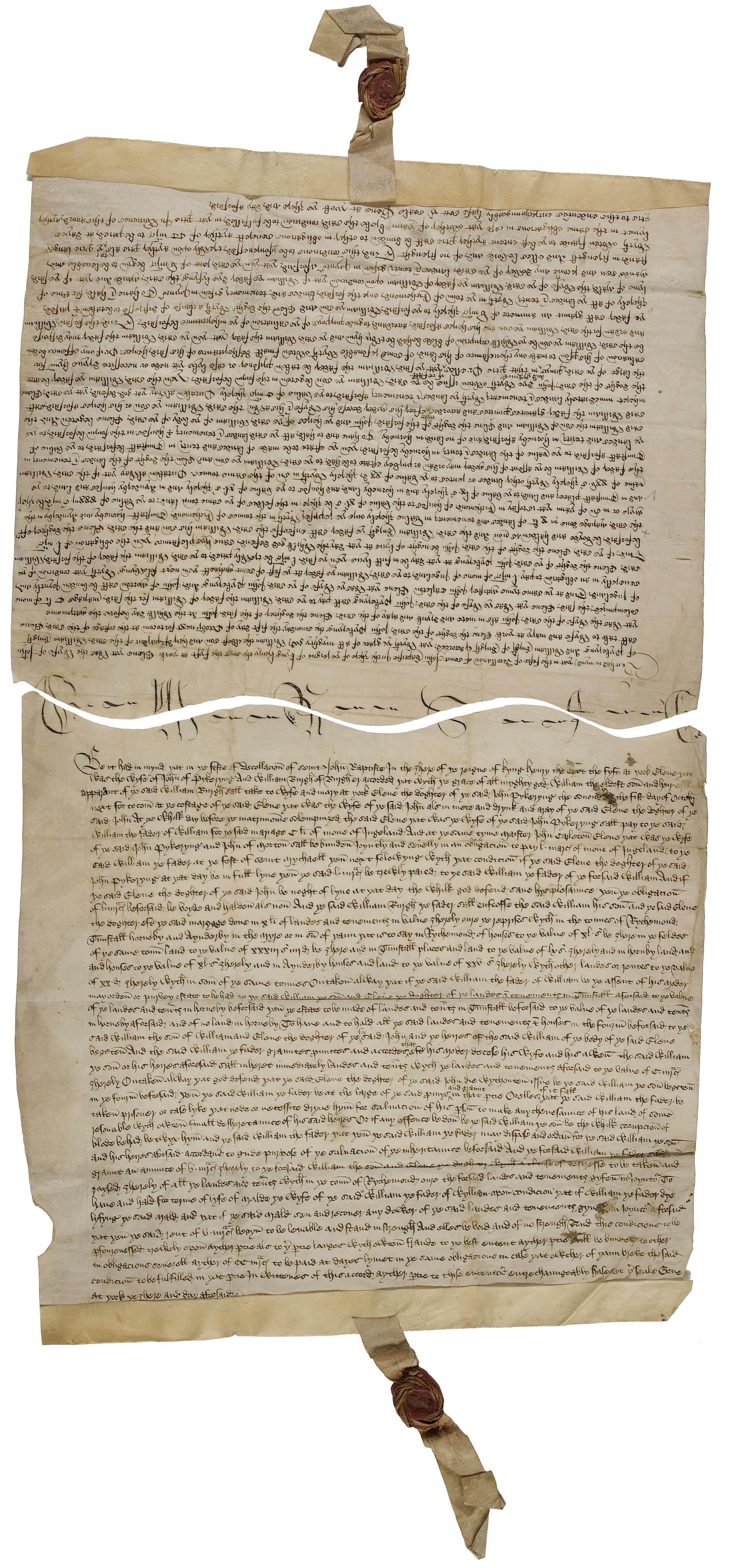

- Left: Page from Bedale Manor Court roll, 1482 [ZBA 17/1/1 folio 2, recto]

- Middle: Marriage settlement, 1427, from the Lawson family of Brough archive [ZRL 1/24]

- Right: 14th-century Medieval music manuscript used as the cover of a court book, 1582-1608, from the Jervaulx Abbey estate archive [ZJX 3/19/110]

Scribes and scripts

Medieval scribes (women and men) worked long hours preparing and copying official and literary manuscripts. They wrote with quills fashioned from goose feathers and used iron-gall ink. Most Medieval documents are written on parchment, or higher quality vellum, produced from animal skin. Paper was not readily available until the 14th century.

Medieval deeds usually followed set formats, using stock phrases, and were largely written in Latin – though could be in Middle English or Norman-French. Scripts merged and evolved throughout the Middle Ages but can be broadly categorised into three main styles – Textura, cursive and court hands:

Example of Textura script

Textura: (also known as Gothic Book Hand or Black Letter) was a formal script used widely from the 12th to 16th centuries, especially in literary documents. Heavy pen-strokes characterised individually formed letters

Detail from Prince Henry’s Book, c.14th century [ZFM 349].

Example of cursive script

Cursive: Anglicana was a freer handwriting style which emerged in England during the mid-13th century, allowing scribes to work quickly and to use abbreviation – useful when copying lengthy official documents. Elements later merged with Secretary hand in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Detail from a marriage settlement, 1427 [ZRL 1/24]

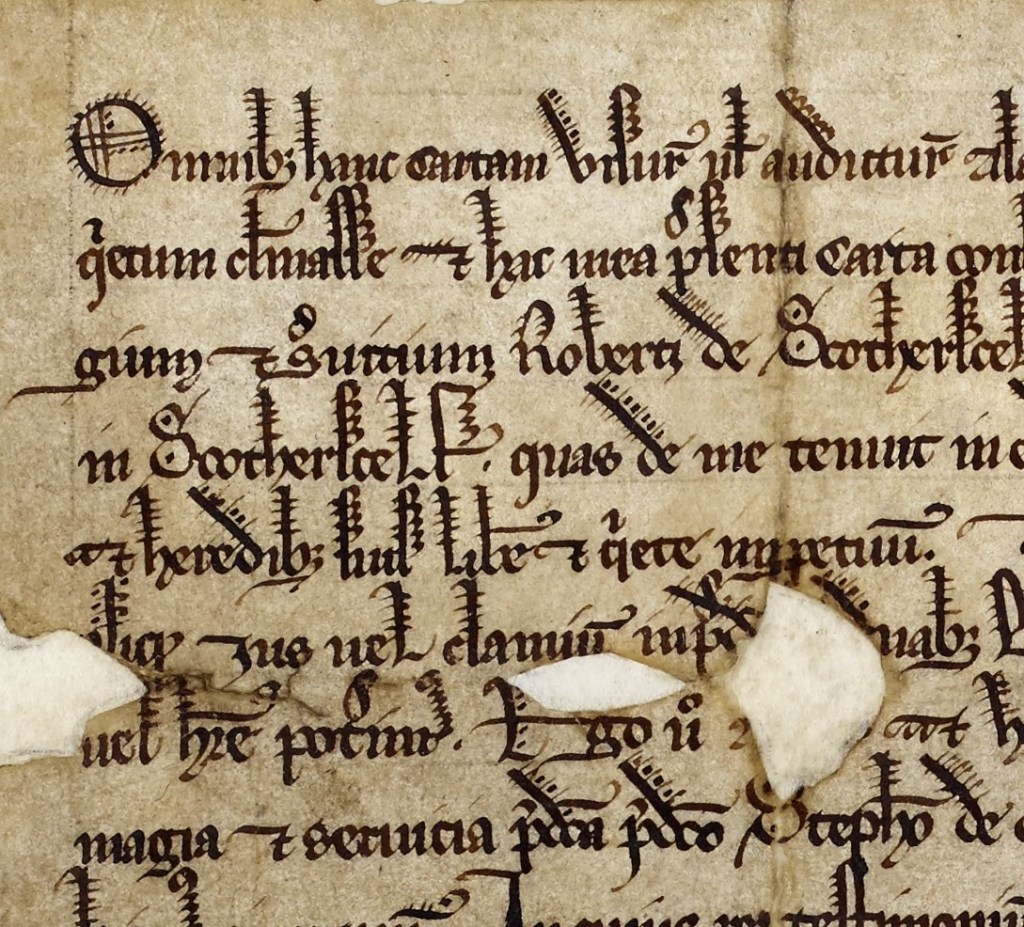

Example of court hand

Court hands: these stylised, spikey scripts were employed by law courts and government departments – some having their own signature styles: ‘Exchequer hand’ or ‘Chancery hand’. Many Medieval charters and other legal agreements are written in a form of court hand.

Detail from the Skutterskelf deed c.1200 [ZFM 20]

Decoration and illumination

Decorations on Medieval manuscripts range from simple to elaborate. Such flourishes on initials and in margins – often using different coloured inks – can indicate important points, thereby helping the reader navigate the text. Manicules (from the Latin ‘little hand’) were commonly used to highlight new sections or noteworthy points – and even numbered whimsical birds and faces were employed by certain scribes working on the Clervaux Cartulary!

Examples of manicules and birds from various deeds in the Clervaux Cartulary (pages 146, 148, 151 and 153) [ZQH 1]

Illumination is the highest form of decoration, using a range of brightly coloured pigment paints embellished and highlighted with gold or silver leaf. Such documents were expensive to produce, so are usually royal or ecclesiastical in nature – like Prince Henry’s Book (next section below) or Letters of Confraternity, which confirmed links between persons or institutions and a religious house, in return for support.

Letter of Confraternity, 1472: Thomas, Provincial Prior of the Augustinian friars in England, to Edmund Mauleverer and Eleanor his wife [ZFL 184]

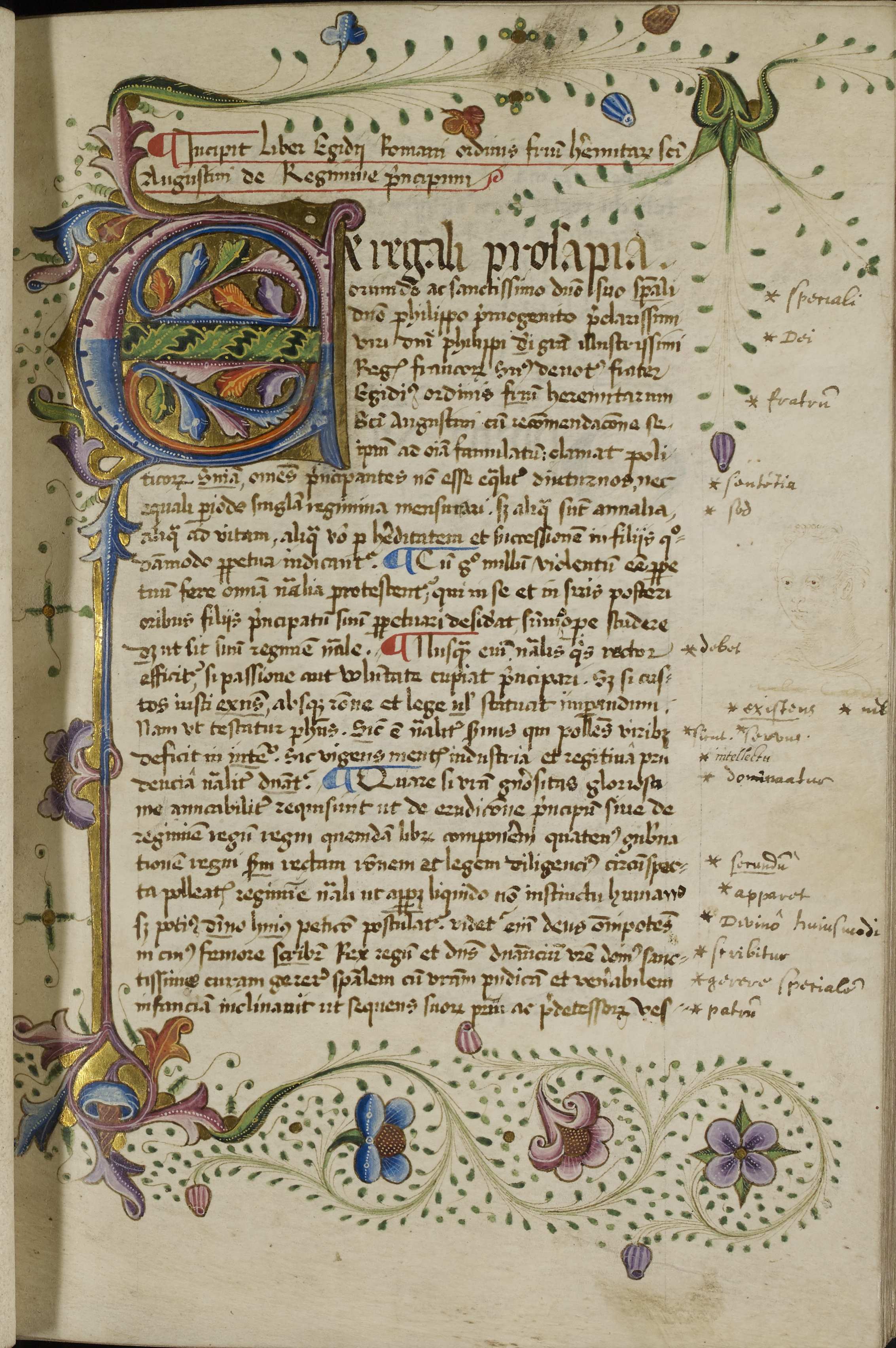

Prince Henry’s Book, from the Chaloner of Guisborough archive

Within the Chaloner of Guisborough archive [collection reference ZFM] is a beautifully illuminated reproduction of De Regimine Principium (The Rule of Princes) [ZFM 349]. Giles Colonna of Rome completed the original in 1279, for Philip the Fair of France (Philip IV). Several copies were subsequently produced, including this version gifted to Henry Frederick, son of King James I.

The main text in this copy appears to be late-14th century yet incorporates a dedication at the start by John Bridges (Bishop of Oxford 1604-1618) on his giving the book to Prince Henry, sometime after he became Prince of Wales in 1610.

Prince Henry is believed to have subsequently presented the book to Sir Thomas Chaloner, on his being awarded the position of Chamberlain in the royal household – thus explaining its presence in the Chaloner family archive. Before he could become king, however, Prince Henry died of Typhoid fever in 1612 aged just eighteen, and his younger brother Charles acceded to the throne instead.

Essentially an instruction manual, a small section shown below of The Rule of Princes has been translated from Latin, to give the reader an indication of the kind of advice imparted:

Detail from Prince Henry’s Book, imparting advice relating to war [ZFM 349]

“Third part of the 3rd book of the rule of princes treating of warlike work and the rule of cities and of the kingdom in time of war.

First chapter. What is the army and for what instituted and what every warlike operation contains.

2nd. Which are the regions in which are the best warriors and from what kinds are tobe chosen warlike men.

3rd. At what age are assigned young men to warlike work and by what signs can be known warlike men.

4th. Which and how many warlike men to have indentured that they might fight well and that it may happen that they make war strenuously.

5th. There are good warriors in cities and noble ones among cultivators and rural people.

6th. Why in time of war it greatly is worth the exercise with arms in that it gradually initiates the warriors in running and jumping.

7th. Why that exercise of the warriors does not suffice if many other things are lacking.

8th. Why it is useful in the army to make ditches and construct castles and in what way the castles are to be constructed and who are to attend to the construction of them.

9th. What and how many things are to be considered in war if a public fight should be committed to.

10th. Why it is useful to carry banners in war and on the appointment of leaders and corporals and of what kind should be those who in the army carry banners before horse and foot.“

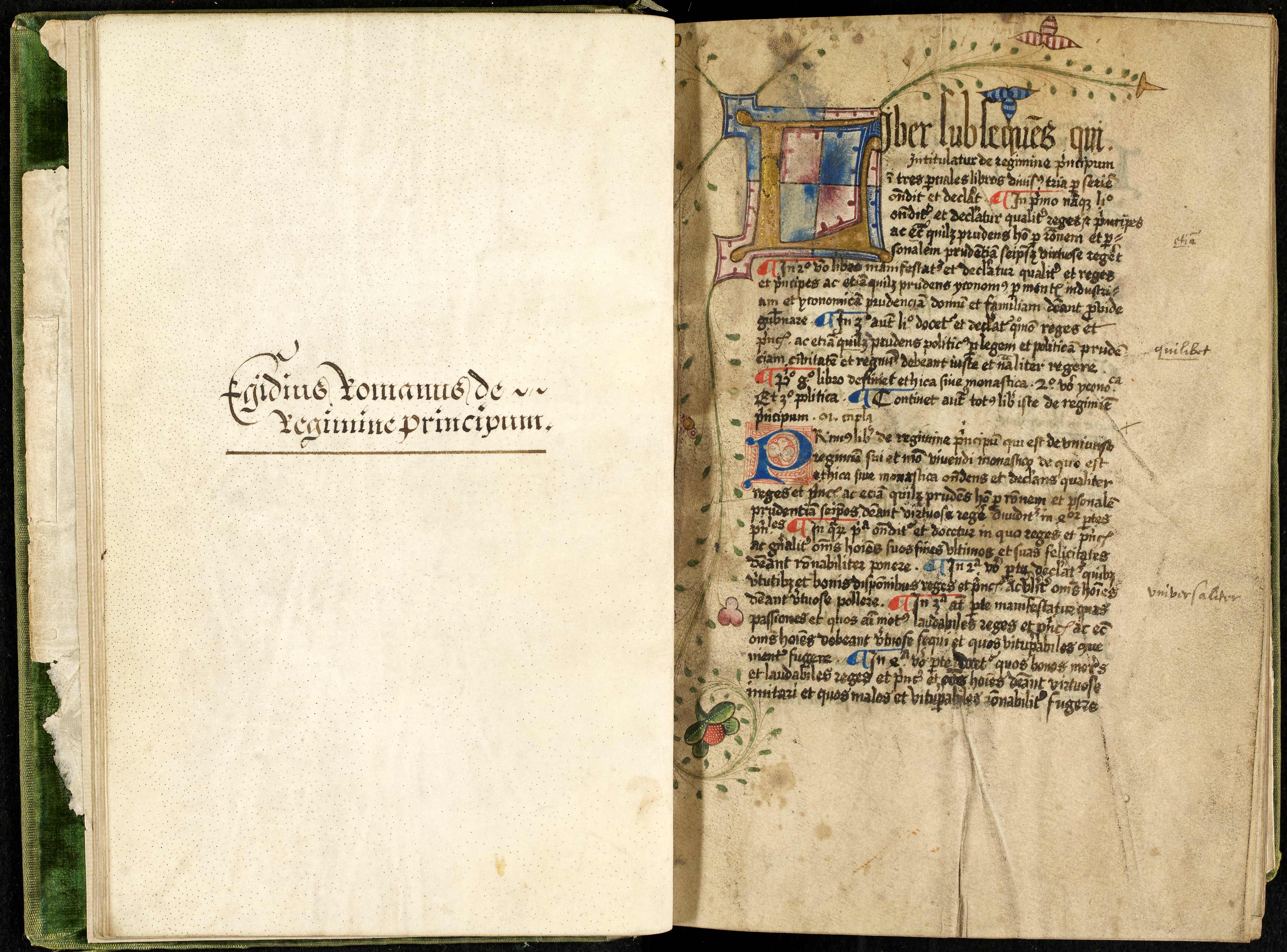

The Clervaux Cartulary, from the Chaytor of Croft archive

A cartulary is a collection of charters and title deeds, usually bound, relating to a particular family or religious institution.

Contained within the Chaytor of Croft archive [collection reference ZQH], the Clervaux family cartulary [ZQH 1] was compiled for Richard Clervaux in the 15th-century and includes deeds stretching back to at least the 13th century.

The Clervaux Cartulary, pages 146 & 148 [ZQH 1]

It contains acquisitions and leases of land, along with personal family documents – including wills, disputes, and marriage settlements. There are even grants of red wine, for life, to Richard Clervaux from Richard III and Henry VII, rewarding his good service!

The deeds are in Latin, with an occasional item in English, and are not arranged in apparent chronological order. A short verse names Cressi as the scribe who compiled the main body of the work in 1450-51. Thereafter, other hands suggest up to eight other scribes may have contributed. At a later point in time the pages are numbered in a 16th-century hand.

Sibthorpe Chronicle, from the Fauconberg (Belasyse) of Newburgh Priory archive

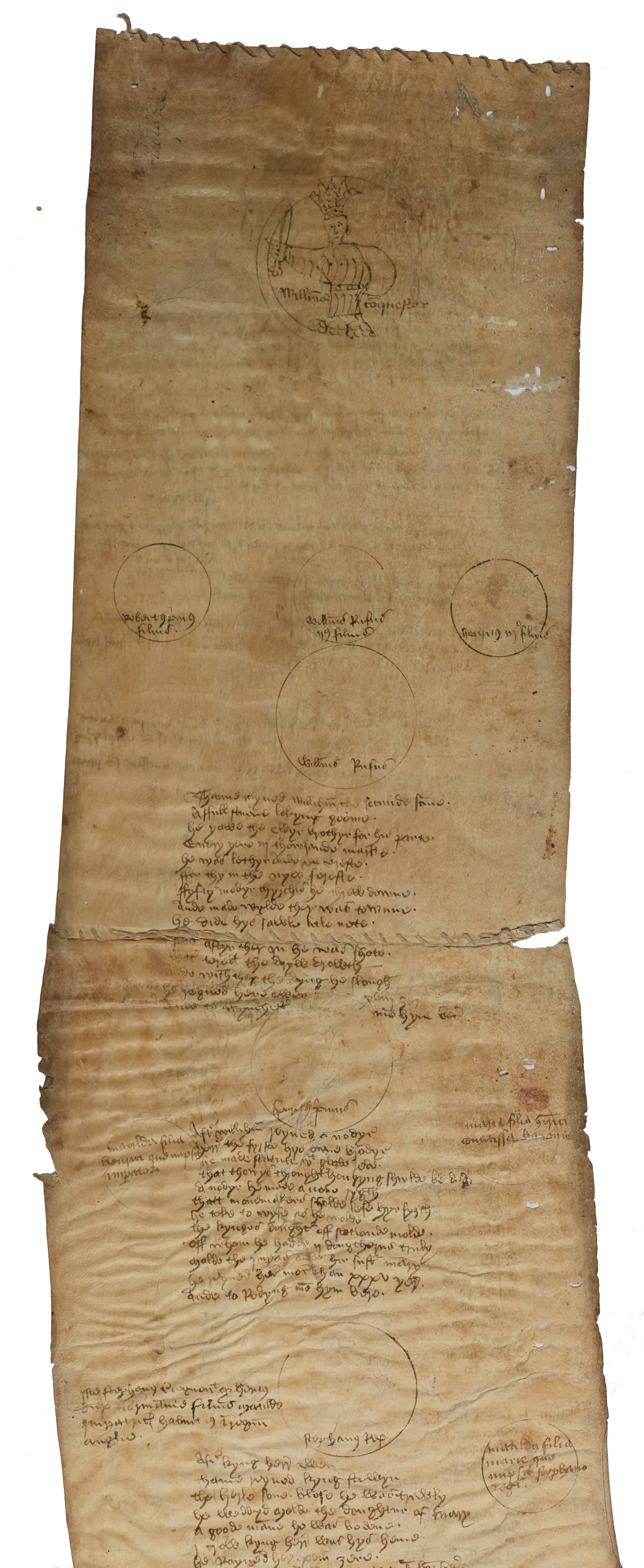

Detail from the Sibthorpe chronicle, showing a depiction of William Conqueror, c. 1429 [ZDV V 55]

The Fauconberg (Belasyse) of Newburgh Priory archive [collection reference ZDV] contains some Medieval deeds relating to places outside of North Yorkshire, including an account roll of Sibthorpe Chantry/College in Nottinghamshire (1410-1411) [ZDV V 55]. Composed on the reverse, and spanning four sections of parchment sewn together end-to-end, is a rhyming mini chronicle of the Kings of England! Thought to have been employed in the instruction of children, it is composed in Middle English, with some Latin, and only William I has been depicted (the circles below are incomplete). Whilst the account roll itself is dated, the chronicle – added later – is not, though is likely to have been compiled shortly after the coronation of Henry VI in 1429.

The four sections of the Sibthorpe account roll, showing the chronicle of the Kings of England on the reverse, c.1429 [ZDV V 55]

Acknowledgments and further reading

Grateful thanks to John Henderson for kindly translating part of Prince Henry’s book from Latin to English [ZFM 349].

Giles of Rome Wikipedia page

Illuminated Manuscript Wikipedia page

The Humour of Medieval Scribes website

Medieval handwriting styles – University of Nottingham webpage

See also the previous blog by Gwyneth on Medieval music: examples of manuscript fragments from our collections