By Gail Falkingham, Record Assistant

Our previous blog on Victorian gardens mentioned developments in the 19th century which led to more efficient and more accessible glasshouses. The collections of the County Record Office include a number of sources which can tell us more about historic walled gardens and glasshouses in North Yorkshire. Many historic maps within our archives record the location of walled gardens and the buildings within and beside them. Plans and elevations show us how these glasshouses were designed and the variety of functions within them. Estate records and correspondence provide further insight into the types of flowers, fruit and vegetables that were grown. Some examples shown here include material from the archives relating to Swinton Park, Upsall Castle, Guisborough and Clifton Castle, near Masham.

Walled Gardens

In the past, nearly every cottage and country house would once have grown its own produce, varying in size from a small vegetable plot in the back garden, an orchard or an allotment, to a large, walled kitchen garden.

These larger kitchen gardens were surrounded by high brick walls, which provided protection from animals and created a micro-climate inside. They supplied food and flowers for the main house, as well as plants and herbs for medicinal use. Fruit trees were trained up south-facing walls, which retained the heat, and some were ‘hot walls’. These were built hollow, with flues and chimneys or vents, attached to boiler houses or furnaces to circulate hot air through them, not unlike the hypocaust heating systems of Roman times. Many walled gardens had glasshouses or hothouses, creating an artificial climate within, in which more exotic varieties could be grown in warmer temperatures, and where the growing season could be extended.

In the 18th century, the height of luxury and status was the pineapple, the most desirable, and yet most difficult, exotic fruit to grow. A great deal of time and effort was expended in growing this fruit and special pineries were built, where the pineapples were grown in pits filled with tanner’s oak bark and manure to keep them warm, and grape vines were often grown above.

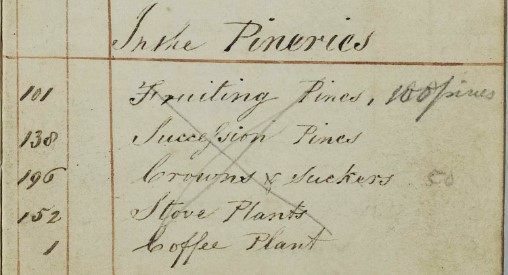

A garden inventory of 1833 from the Duncombe Park archive (ZEW XVI 4/4) lists the contents of the pineries as:

101 Fruiting Pines

138 Succession Pines

196 Crowns and Suckers

152 Stove Plants

1 Coffee Plant

Earlier walled gardens in the 17th century tended to be built close to the main house. By the later 18th and 19th centuries, they were placed further away, out of view. They are mainly rectangular in shape, although sometimes the south wall was curved, as at Kiplin Hall, so as to retain heat. A zig-zag or serpentine shape (sometimes known as ‘crinkle crankle’) served to trap the heat as well, but also saved the amount of bricks that were required (especially popular following the tax on bricks in 1784). Sometimes, the outer sides of the garden walls and the adjacent ground were taken advantage of. Hardier fruits and vegetables were grown here, in what are known as ‘slip gardens’.

Helmsley Walled Garden

A good example of a walled garden still in use today can be found at Helmsley, on the edge of the North York Moors National Park. The garden provided vegetables, fruit and flowers for Duncombe Park and glasshouses for growing exotic and tender plants and fruits were introduced in the 19th century.

Historic maps from the Feversham/Duncombe of Duncombe Park archive (ZEW) show the walled garden at some distance from the main house, lying adjacent to the castle moat. The garden has been in this position since about 1758, replacing the original garden which was located further down towards the River Rye and which was destroyed by a great flood in 1754. A plan of 1822 shows detail of some of the layout including the glasshouses (ZEW M 35).

Swinton Park Hot Houses

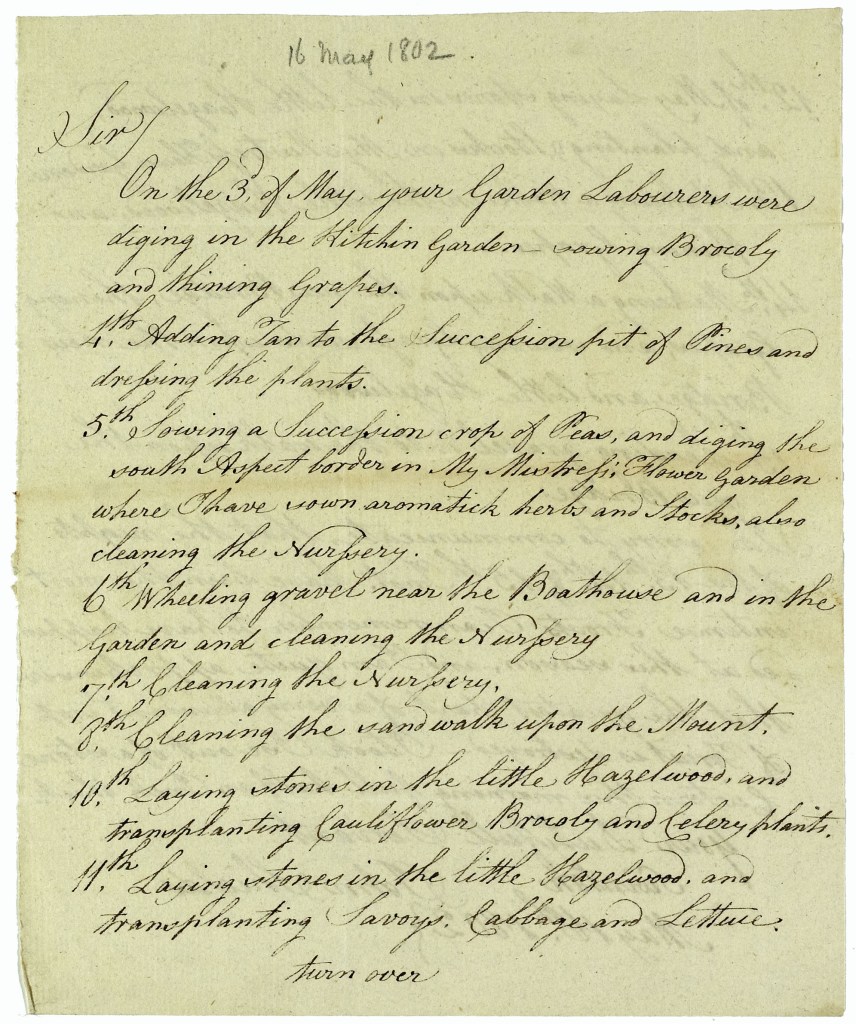

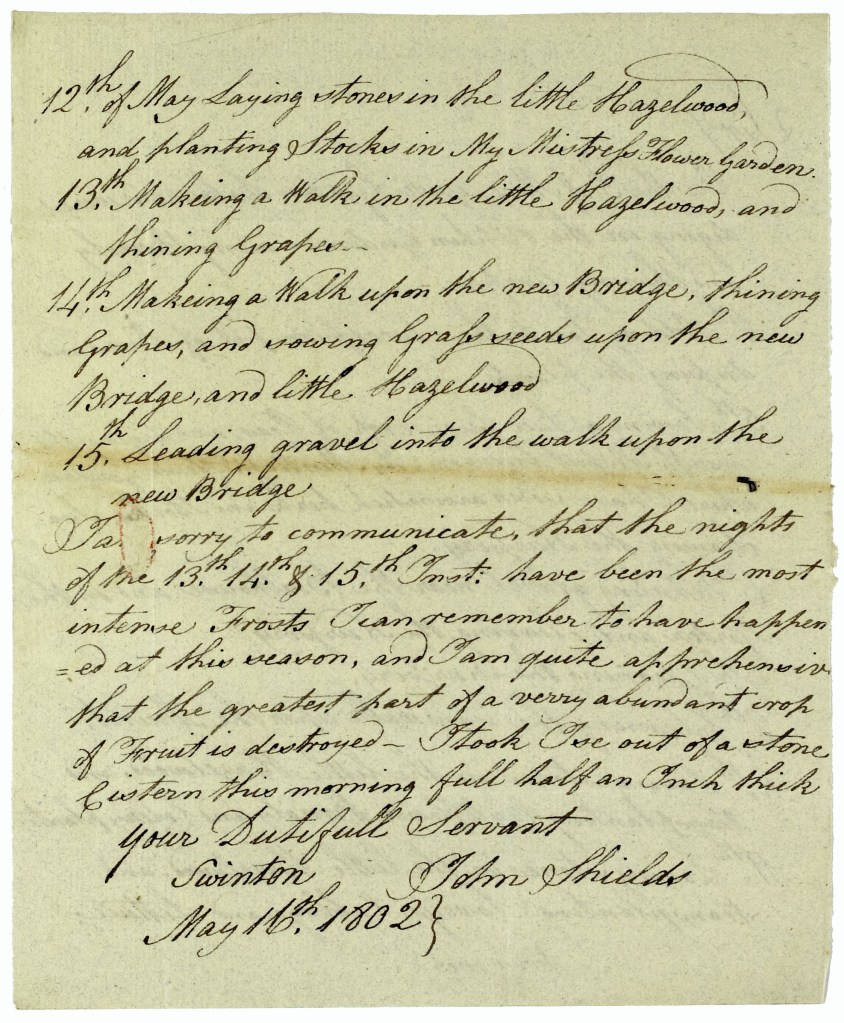

Copies of correspondence in the Swinton Park archive (ZS) provide a wonderful insight into the daily life of the garden in the early 1800s. John Shields, head gardener to William Danby, wrote fortnightly to his employer whilst he was away from Swinton to keep him fully informed of the work being undertaken.

These letters contain many mentions of the greenhouses and hot beds. A number of varieties of fruit were being grown, including figs, nectarines, apricots and peaches, as well as melons, grapes and pineapples.

In a letter dated 21 March 1802, written by John Shields to William Danby whilst he was away at his property in Devon he describes:

“General observations in the Hothouse part of the Pines have shewn fruit they are very fine ones but want a little tan, the Vines shew plenty of Grapes some of them in bloom. In the Peach house the fruit about the sise of Peas the crop as usual, figgs about the sise of Plumbs & more of them than I ever had before. Green house plants in good health, and plenty of Bloom upon the Walls in general part of the Apricots have a few expanded flowers upon them”.

In a letter two months later, dated 16 May 1802, John Shields recorded that he had been thinning grapes on 13 and 14 May. He also notes his concern that the unusually cold and frosty weather for the time of year would destroy ‘the greatest part of a very abundant crop of fruit’.

The extensive, 4 acre, walled garden at Swinton Park, can be seen on the above plan of the gardens, deer park and pleasure grounds of William Danby of 1820 (ZS). Two, large enclosed areas are labelled as no.9, ‘Kitchen Gardens’, with the nursery and orchard (no.30) beyond to the west (on the left).

Scampston Hall Glasshouses

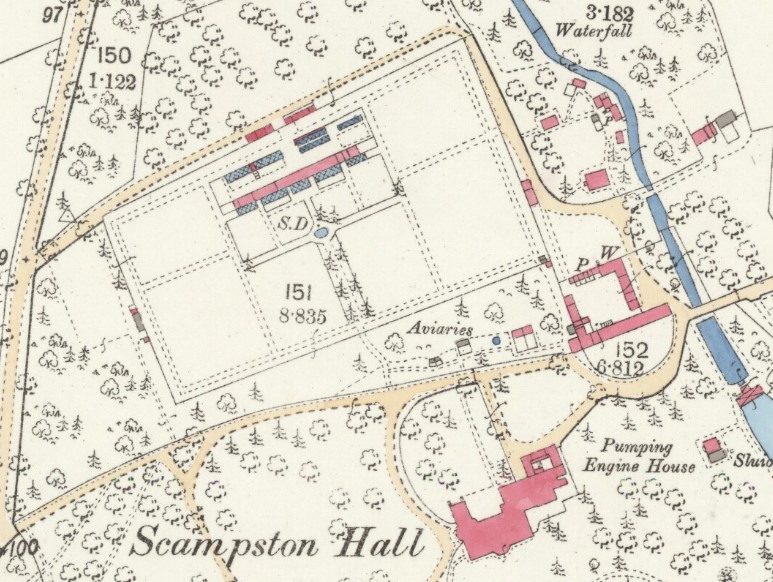

The large walled garden at Scampston Hall, shown on the first edition 25 inch to the mile Ordnance Survey map of 1891 (Yorkshire sheet CVIII.13, surveyed 1888)

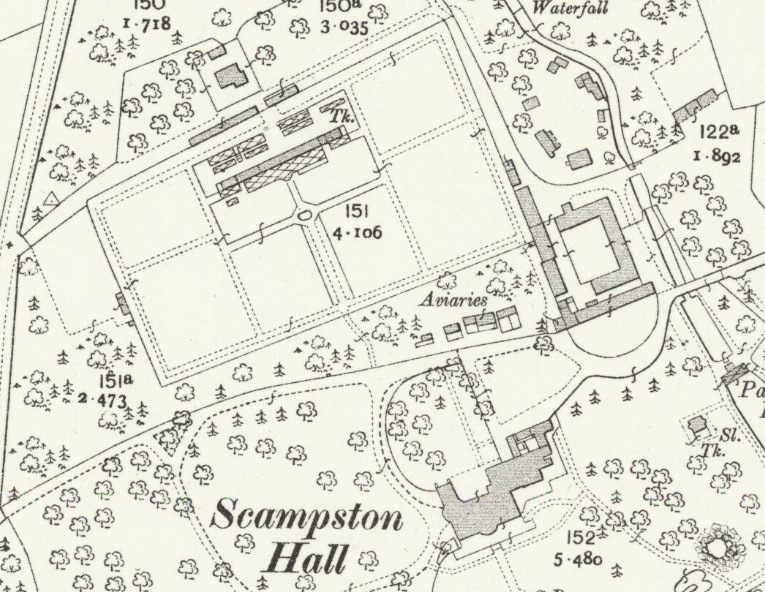

The new Richardson conservatory at Scampston Hall, shown on the second edition 25 inch to the mile Ordnance Survey map of 1911 (Yorkshire sheet CVIII.13, revised 1909)

A fine example of a restored William Richardson conservatory, originally built in the walled garden in 1894, can be seen at Scampston Hall in North Yorkshire. As can be seen by the differences between the first and second edition Ordnance Survey maps above, the new conservatory replaced five, earlier glasshouses.

It is easy to spot glasshouses on later Ordnance Survey maps, as they are shown with cross-hatching to denote the glass roof, and are also coloured in blue on the first edition 25” editions of the 1890s. There may also be a shallow dipping pond, which often took the overflow from the greenhouse rainwater tanks, and sometimes had a decorative fountain. This water was used by the gardeners and so named as they dipped in their watering cans.

Victorian Glasshouses, Hothouses and Conservatories

In the mid-19th century, following the abolition of the tax on glass in 1845, and the Great Exhibition held in 1851 in Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in London, greenhouses, conservatories and vineries gained even more popularity and were a common feature of Victorian gardens. Technological developments, such as James Hartley’s sheet glass process of 1847, and the introduction of prefabricated cast iron enabled the middle classes as well as the wealthy to have greenhouses. Exotic fruits, as well as tender plants, such as orchids, brought back from the overseas expeditions of Victorian plant hunters, could be grown in the artificially warm environments provided under glass.

W Richardson & Co. Glasshouses

W Richardson & Co. of Darlington were noted designers and suppliers of glasshouses in the 19th century, not only in Yorkshire, but all over Europe. Beginning as Richardson and Ross in the 1850s, they parted ways in the early 1860s. William Richardson was a Quaker, born at Langbaurgh Hall in Great Ayton, North Yorkshire. He went on to found the North of England Horticultural Works off Neasham Road in Darlington in 1874, and produced a range of greenhouses, hothouses, palm and orchid houses until his death in 1921. These were heated by hot water boilers and radiators, and made from Baltic pine sourced from Scandinavia and Russia.

Upsall Castle Hot Houses

The letter books of Edmund Henry Turton in the Turton of Upsall collection (ZT), provide a fascinating insight into the purchase and specification of a range of hot houses for the new kitchen garden at Upsall Castle. In letters dated March 1863, Turton appears to be negotiating with suppliers for the best price for the specification he requires. The range of hot house buildings were supplied by Ash & Company, Sheffield, and the heating system for these provided by J & C Ellis of the Norfolk Foundry, Sheffield.

In a letter from J & C Ellis, of the Norfolk Foundry in Sheffield, dated 4 March 1863, the heating specification is given as follows:

“Sir, we propose to furnish warming apparatus for your conservatory 30 x 16 [feet] to maintain a temperature of 45 deg [degrees Fahrenheit] in coldest weather. Also for (2) vineries 20 x 14 to maintain a temperature of 80 deg. Also for (2) peach houses 20 x 14 with a temperature of 60 deg with all necessary piping elbows, branches, stop valves so that they could be warmed separately or all together as circumstances required. Also 2 ~ 2 in [inch] pipes through Mushroom House. Also warming apparatus for Camillia House 18 x 16 temperature 50 deg. 2 in main pipe for ditto from Boiler. Also 2 ~ 3 in pipes for bottom heat in Cucumber bed & 2 ~ 3 in pipes for top heat with all necessary elbows, syphons, branches, air pipes, cement, Large improved Double conical boiler, double furnace doors & frame ~ soot doors, Boiler top plates, furnace bars, feed cisterns, expansion boxes. Mens time fixing & carriage of materials.

All these will be undertaken for the sum of one hundred & forty two pounds ten shillings (£142-10/). Ornamental grating for stonework 7 inches wide 2/6 per yard. 9 in wide 3/ per yard, 12 in wide 4/9 per yard”.

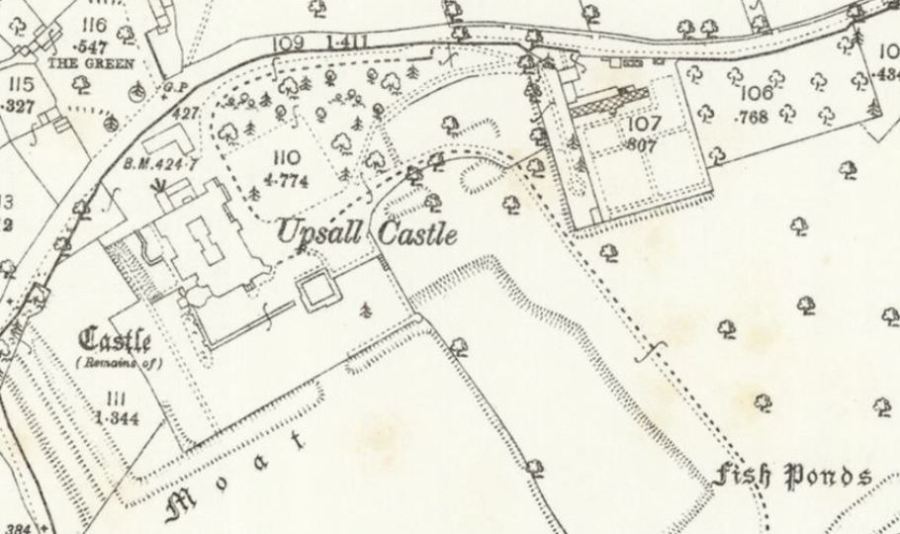

Whilst we do not have the plans which accompanied this quote, the first edition, 25 inch Ordnance Survey map of 1893 shows the kitchen garden with the glass houses located at its northern end, facing south. There is also an adjacent, enclosed orchard to the east.

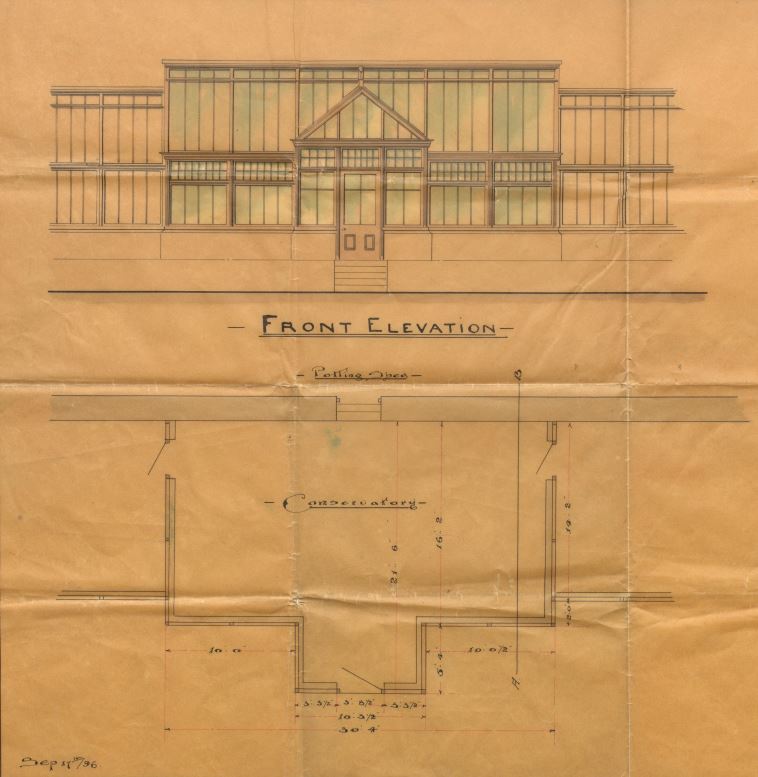

The Turton of Upsall archive also contains a Richardson & Co. conservatory plan for Upsall Castle, dated 17 September 1896 [ZT I 8/2], prepared shortly after the Ordnance Survey map was published. This plan was for Sir Edward Russborough Turton, who inherited Upsall in 1896 upon the death of his father, although it is not known if this was ever built.

Guisborough Glass Houses

The Manor of Guisborough collection (ZFM), contains a W Richardson & Co. coloured plan and front elevation drawing for ‘A Range of Glass Houses for Colonel Chaloner at Guisborough, Yorks’, dated 12 May 1902, ‘Scheme no. 3’.

This shows an elaborate complex over 92 feet long, including provision for a tomato house, boiler chamber and stove house with plant pit, a mushroom house, potting house and a central plant house projecting forward of the two wings. Internally, there are cisterns for water, iron staging and wires on the rear walls to support climbing plants and fruit.

The same collection contains a blue print by Richardson & Co. for Colonel Chaloner showing a number of glass house cross sections dated 1st April 1902. These show the tomato house, early and late vineries, peach house, melon house, stove, mushroom, plant and boiler houses.

Clifton Castle, near Masham

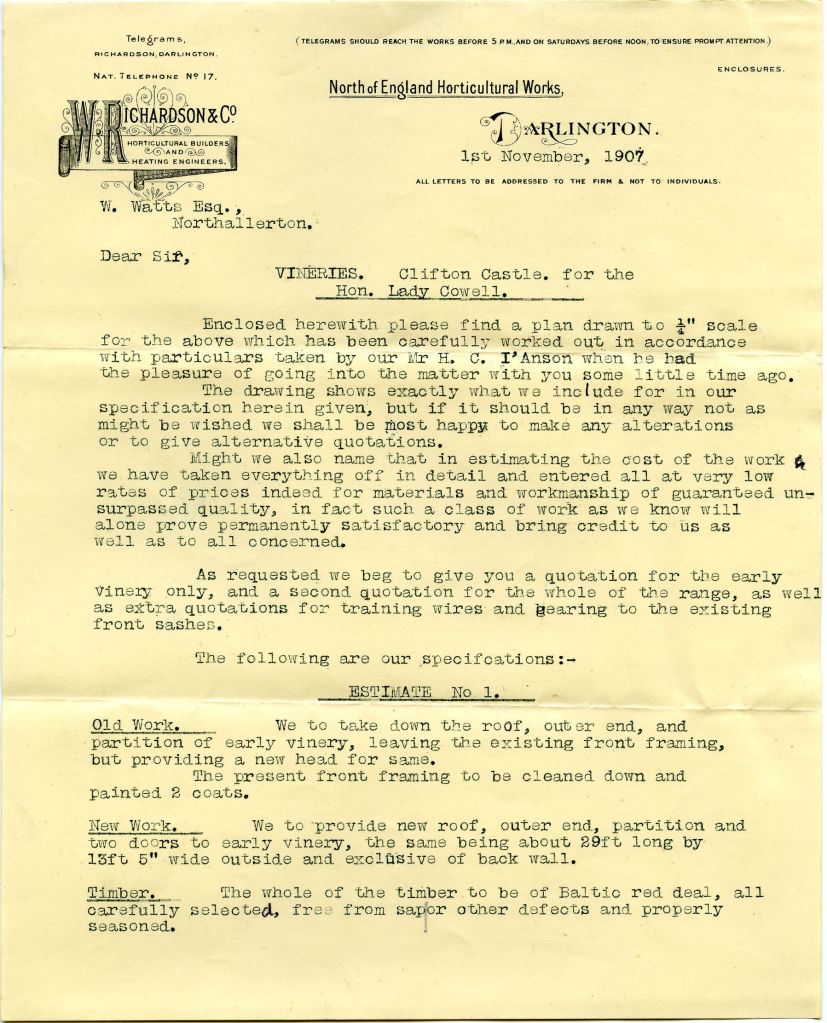

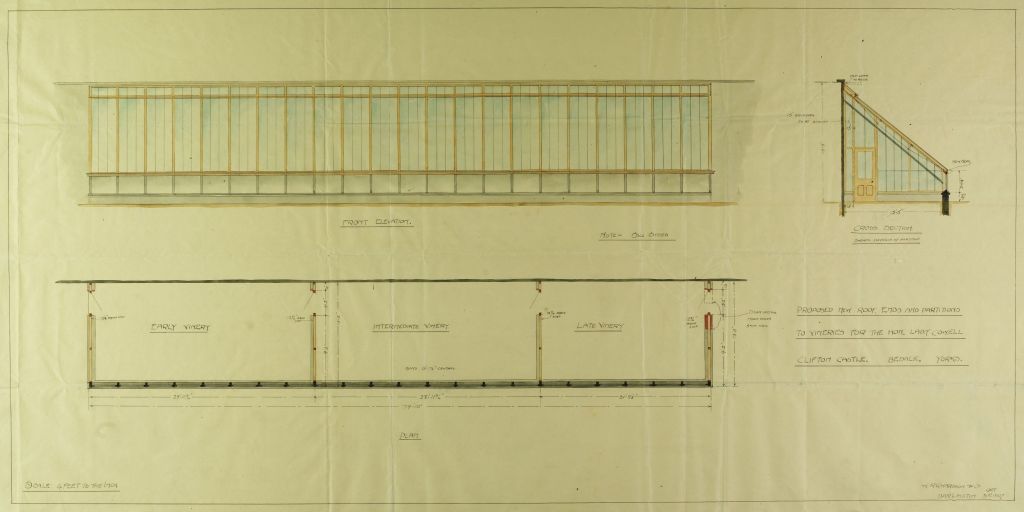

In the archive of Clifton Castle (ZAW), a Richardson plan of proposed renovations to the vineries at Clifton Castle for the Honorable Lady Cowell, dated 31 October 1907 is accompanied by the related estimate for the works.

This letter, dated 1 November 1907, details the provision of a new roof, doors and partition walls, as well as re-glazing. The timber is to be of Baltic red deal (pine), ‘the whole painted with three coats of best genuine white lead paint, manufactured by the Dutch Stack process, the wood work finished white inside, the ironwork pale green, and the spouts and down pipes dark brown’. Everything was clearly thought out to the last detail, even the glass roof panes were to be ‘cut with elliptical-shaped ends, so as to run the rain water down the centre of the glass and away from the glazing bars‘.

The ‘Dutch Stack’ process referred to is an historic means of producing paint which is thought to date back to Roman times. It involves placing coiled strips of lead in earthenware pots, exposing them to acetic acid (vinegar), moisture and carbon dioxide for approximately twelve weeks. Carbon dioxide and constant heat is provided by the slow fermentation of horse manure or tanner’s bark in which the pots are stacked. The lead strips are slowly transformed into lead carbonate, which flakes off as friable white pieces. These are then mixed with an oil, such as linseed, to make the paint. Nowadays, lead carbonate is no longer used as the main pigment in white paint as it is poisonous.

The three compartments shown on the plan are what is known as a succession vinery. This involved ‘forcing’ the grapes out of season by replicating the environmental conditions necessary for the grape vines to grow, providing different amounts of heat in each area at different times of the year.

Once forcing had started, a crop of ripe grapes could be expected five or six months later. A crop begun in November, would be ready to eat in April; at Christmas by May or June, and in February by the summer, hence the early, middle and late vineries shown on the plan.

Further reading

‘Glasshouses’ by Fiona Grant, 2013, Shire Publications Ltd

‘A History of Kitchen Gardening’ by Susan Campbell, 2016, Unicorn Publishing Group

Previous Garden History posts on the blog:

Sources for Researching Garden History

I live at Charlton Manor in Knaresborough. When I first moved here is 2006 the vinery wall which had been painted white was still in place as were the metal rings and wires to support the vines. I believe there are records that peaches and grapes were grown (not sure about pineapples!) and part of the orchard still bears hoards of apples each year.

Thank you very much, very interesting!

Sent from my iPad

>

Excellent piece and most interesting. Another source for finding glass houses, orangeries etc is in sale notices where even more modest houses advertised for sale had a glass house. The 1911 Valuation surveys also sometimes include this information.

What a wonderful Sunday afternoon read, and what fantastic archives you have. More garden history blogs like this please!

Excellent reading! We are personally interested in the Richardson & Co glasshouses as we have one of their orchid houses in our front garden albeit sadly without glass and only the framework and ironwork remaining. Even though it is slowly decaying its still fascinating to see how much effort and work had been put into it.