Treasures from the Parish Chest: exploring North Yorkshire’s church history from archives to architecture

Catterick, St Anne, 1412 building contract

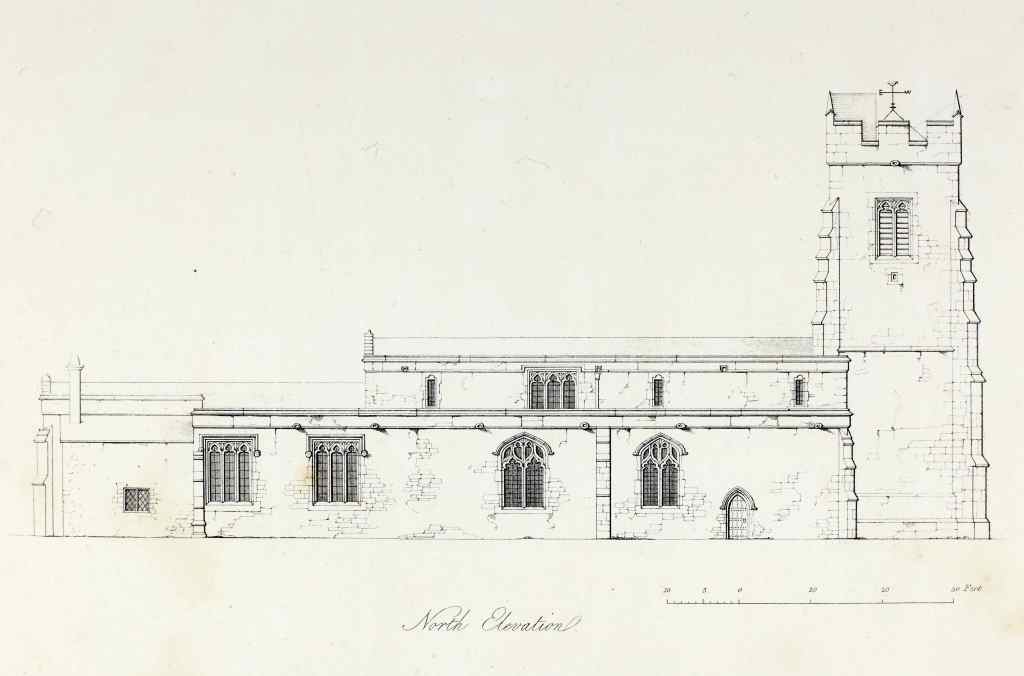

The earliest item on display in the exhibition is this early-15th century contract for the building of St Anne’s church, Catterick, from the Lawson family of Brough archive [ZRL 1/20].

This document is one of the oldest contractual documents written in English. It is an agreement between the benefactors of the church, Dame Katherine Burgh and her son William, and their stonemason, Richard of Crakehall. He undertakes to pull down the stonework of the old church and build a new one, supplying all the labour and any extra stone as required. His employers will provide the carriage for all materials and scaffolding.

The building is to be completed in three years, with an extra year to complete the parapets. His payment is 160 marks, with an extra 10 marks and a gown if he completes the job on time. The contract specifies the details of the new church. The quire (choir) shall be 55ft by 22ft, with walls 24 feet high; the nave 70ft in length with two aisles, 11ft wide and with four arches. The aisle walls shall be 16ft and the nave with clerestory shall be 26ft. At the west end he shall leave bonding stones for a tower, and to the north shall be a door for a vestry, for the future building of which he shall also leave bonding stones.

This contract is published as: Catterick church, in the county of York: a correct copy of the contract for its building, dated 1412 illustrated with remarks and notes by The Rev James Raine, M.A. librarian of Durham Cathedral, and with plates and views of elevations and details by Anthony Salvin F.S.A. architect. Published by J. Weale, London, 1834.

Stonegrave church book, 1678-1941

Stonegrave Minster is considered to be the oldest recorded minster church in England, appearing in documentary evidence of 757 AD. Inside the church, there is a collection of 10th century sculpture, comprising a fine cross shaft and other fragments, although little of the pre-Conquest structure survives.

Images in Stonegrave Minster (Holy Trinity) church book 1678-1941 [PR/STV 3]

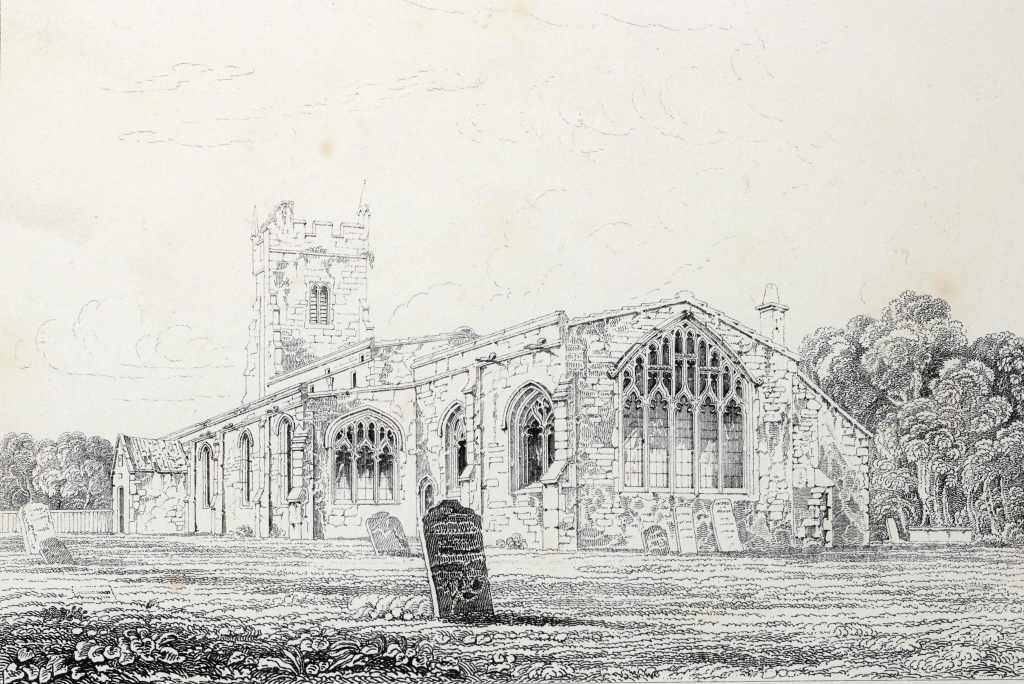

The church book contains some early images, dated April 1861, labelled ‘Old church of Stonegrave – exterior and interior previous to its restoration’. This restoration was subsequently carried out 1862-1863 by the architect George Fowler Jones of York.

As an example of how parish records can inform historical research, the above images from 1861 were used in a recent postgraduate research project at the University of York. Using a multi-disciplinary buildings archaeology approach, including archival research, stratigraphic and physical analysis, measured building survey, phased plans and sightline analysis, Elanor Pitt explored what the physical and documentary evidence for Stonegrave Minster could reveal about the form, fabric, use and experience of the Post-Medieval church. Her 2019 MA dissertation was titled: Not all those who wander are lost: Reconstructing the Post-Medieval Phase of Stonegrave Minster using a Buildings Archaeology Approach.

Additional information about church restoration and rebuilding in the Victorian period can be found on this page.

Faculties

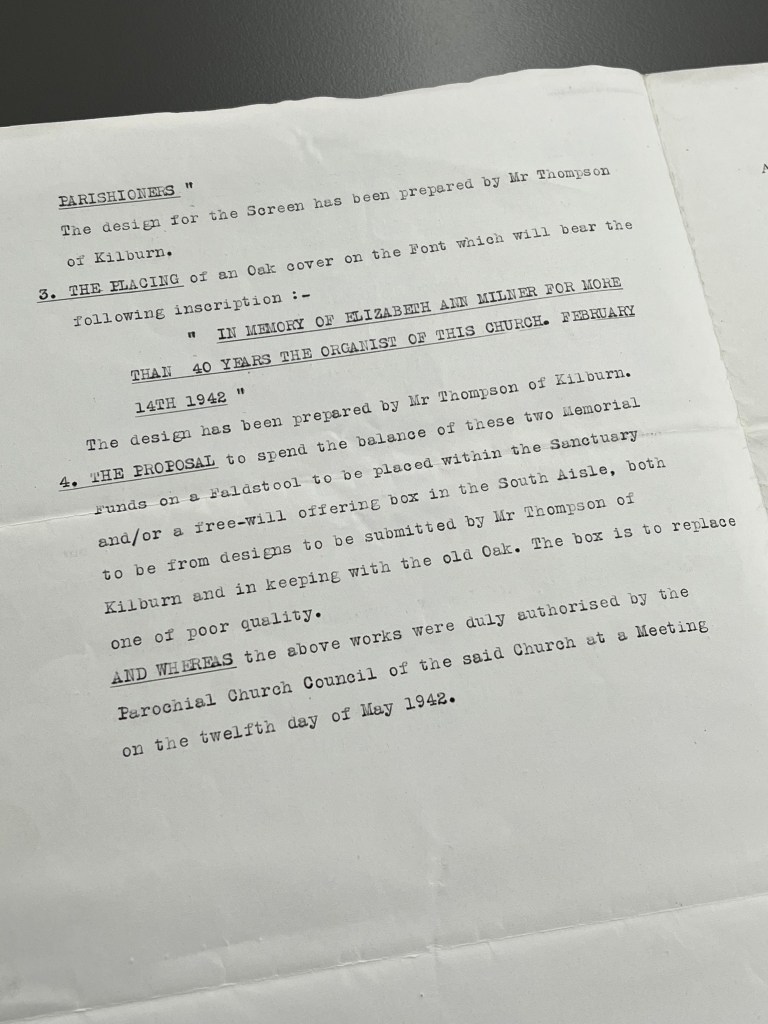

Through the Church of England’s own system of planning control, all works, alterations and additions to parish churches, their churchyards and contents require faculty approval. A faculty is a permissive right to undertake works to a church building or its contents. This is governed by canon law, ecclesiastical law and heritage law, in addition to any planning permission that might also be required.

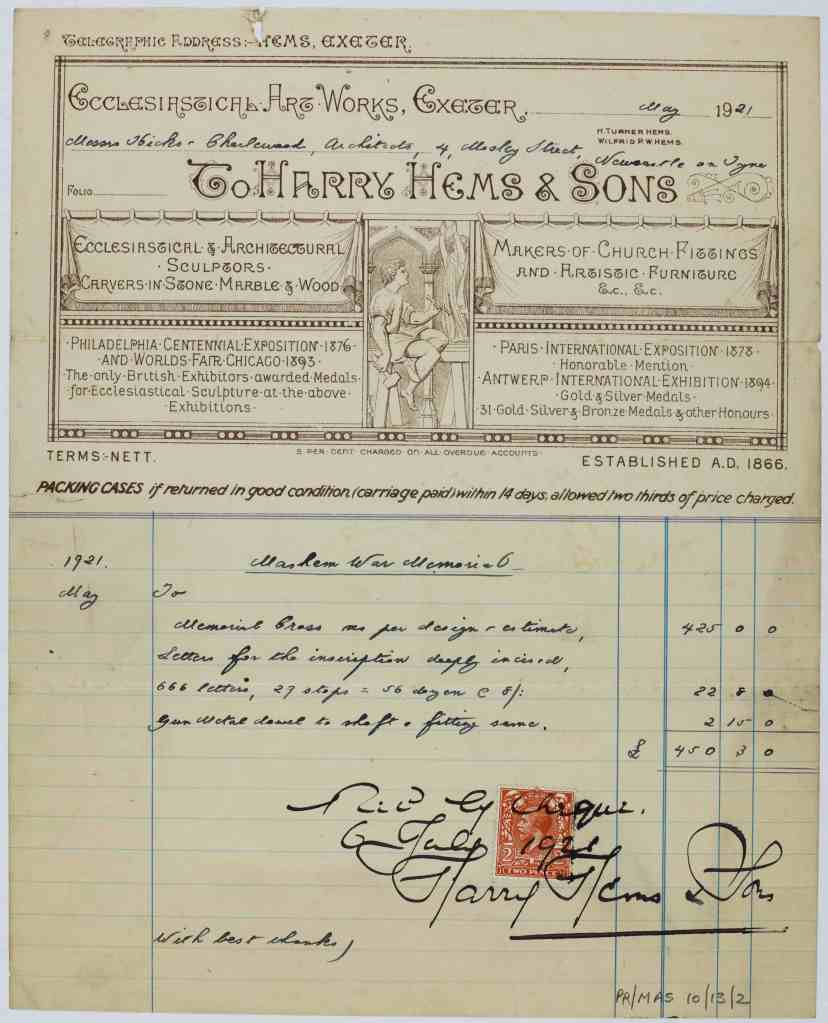

Many faculties can be found in parish record collections. The drawing of the interior of Masham, St Mary from 1969, below left, was made to accompany an application to the diocese for a faculty to change the position of the altar [PR/MAS 9/51]. Examples of other faculties can be seen for Kirkdale, St Gregory on this page, and for Masham churchyard war memorial further down this page.

The churchyard and burials

Every parishioner had a right to be buried within their parish. Whilst members of the nobility and gentry were often buried and commemorated on memorials within the church itself, the majority of the population were interred within the churchyard outside. Most surviving gravestones date from the 18th century or later, although not everyone could afford to pay for an engraved headstone and many graves would have originally had wooden markers, which have not survived.

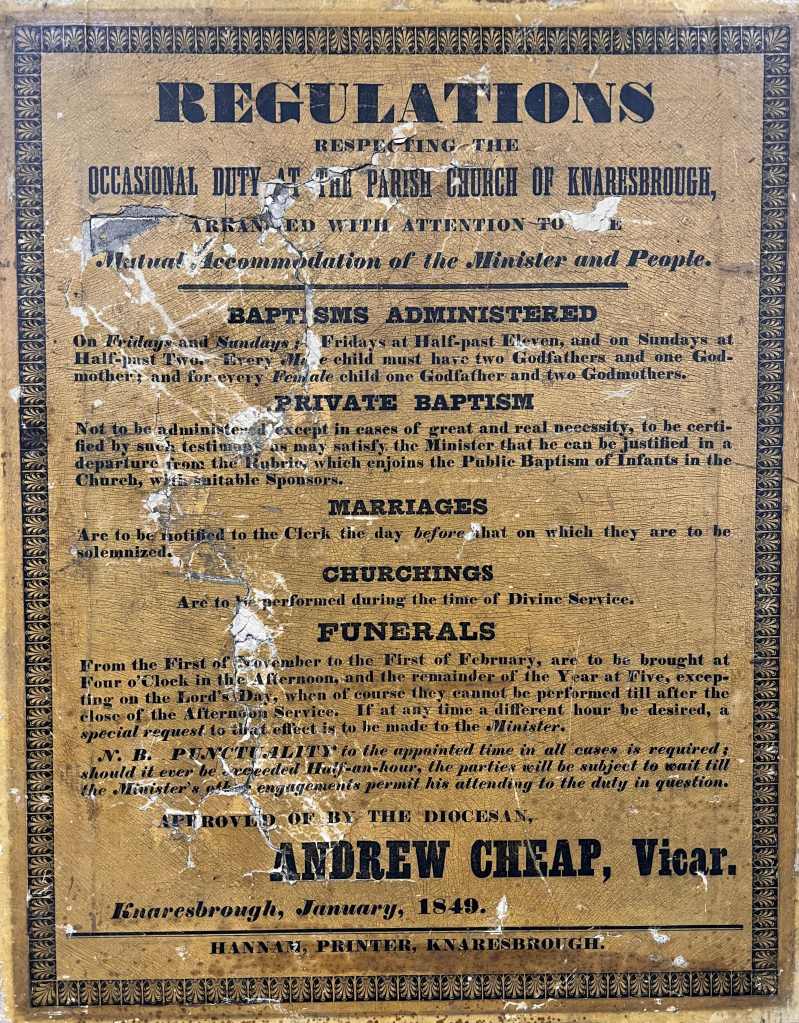

Each church had regulations for burials. In Knaresborough, in 1849, for example:

“Funerals from the first of November to the first of February, are to be brought at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, and the remainder of the year at 5, excepting on the Lord’s Day, when of course they cannot be performed until after the close of the afternoon service. If at any time a different hour be desired, a special request to that affect is to be made to the Minister.”

The church levied a fee for burials, as can be seen in the examples from Great Ayton and Kirkdale above. The Great Ayton sexton’s burial book includes a copy of a resolution passed at a meeting of the parish ratepayers on 3rd April 1861 [PR/AYG 7/3/4]. It was resolved that:

“As the value of money is greatly altered since the present fees were fixed, and the graves are now made much deeper, so that the fees are not now a proper remuneration for funerals. It is agreed by this meeting that the fee to the clerk for his attendance as clerk and for making the grave five feet deep be four shillings instead of two shillings as at-present and a shilling extra for one foot deeper.”

By the 19th century, many church burial grounds were becoming overcrowded. The Burial Act of 1853 enabled local authorities to administer their own cemeteries and thus relieve the problem of overcrowded churchyards. Where a cemetery was created, a Burial Board was appointed by the vestry meeting until 1894, when the duty passed to the District or Parish Council under the Local Government Act. The Local Government Act, 1972 abolished Burial Boards and their powers passed to district and parish councils. The Record Office holds some records of Burial Boards [search for ‘Burial board’ in our online catalogue to see a listing]

Churchyard plans

Where parish records include a churchyard plan, they rarely have an accompanying guide to identify the names associated with plots. That such a guide would have originally existed is suggested by the numbering of the grave plots, as in the examples below.

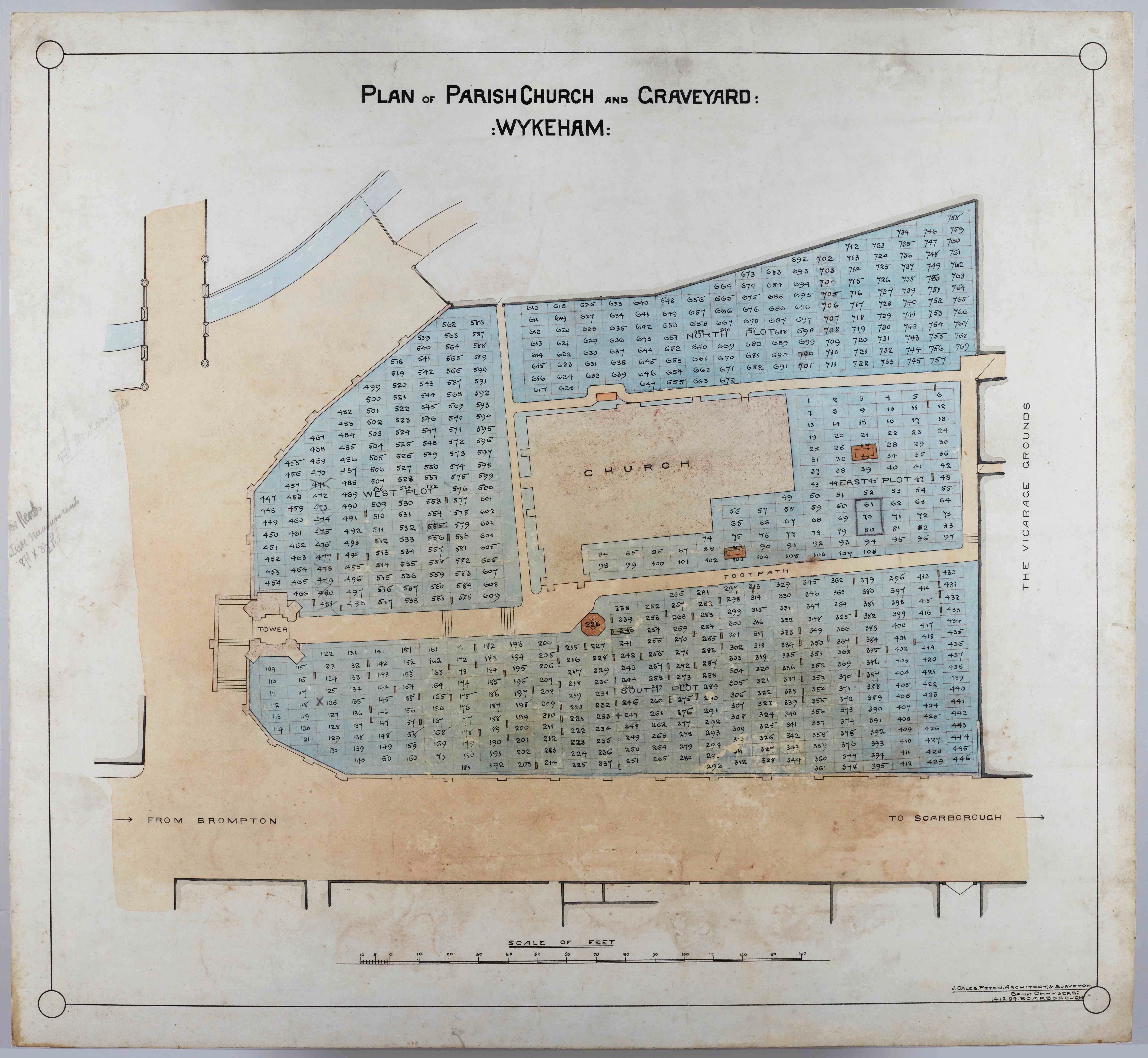

Plan of churchyard, Lastingham, St Mary surveyed and drawn by Richardson & Son, Lastingham, 1878 [PR/LAS 5/8] and Wykeham, St Helen’s & All Saints church and graveyard plan by J. Caleb Petch Architect & Surveyor, Scarborough, 14 December 894 [PR/WYK 10/1]

Plan of Richmond churchyard surveyed by William Legat, 1867

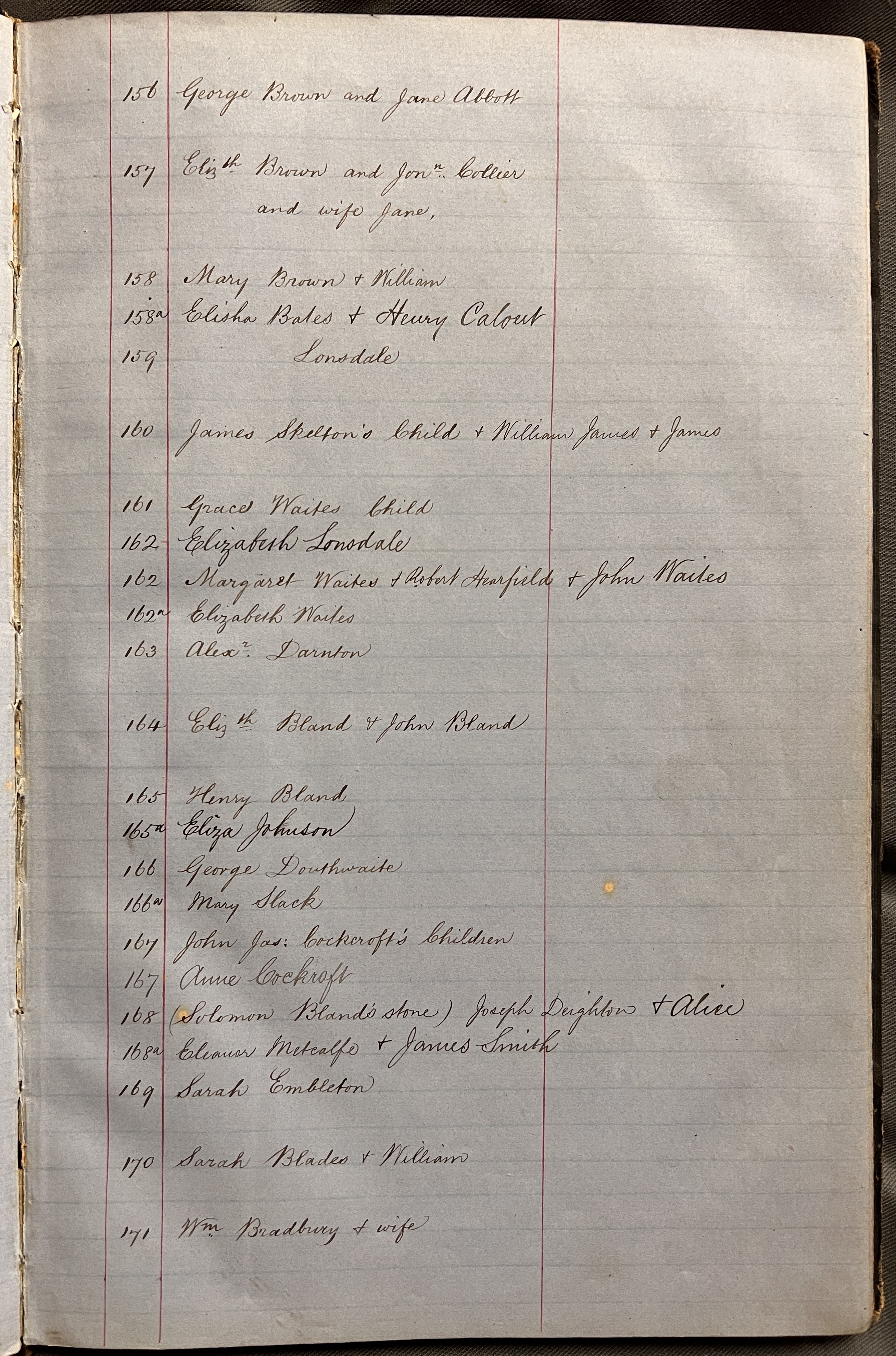

Due to lack of space in the churchyard at Richmond, St Mary, William Legat, a land surveyor, was employed by the Borough to survey the area to determine where they could place more grave plots [PR/RM 9/4/6]. He numbered the existing grave plots on the plan, and listed all the related names both alphabetically and by plot number in an associated reference book [PR/RM 9/4/5].

Map of the churchyard, Richmond, Yorkshire surveyed by William Legat, 1867 [PR/RM 9/4/6]

Foolscap-sized book containing ‘Reference to the map of Richmond churchyard, arranged numerically and alphabetically by William Legat, Richmond’, undated (c.1860s) [PR/RM 9/4/5]

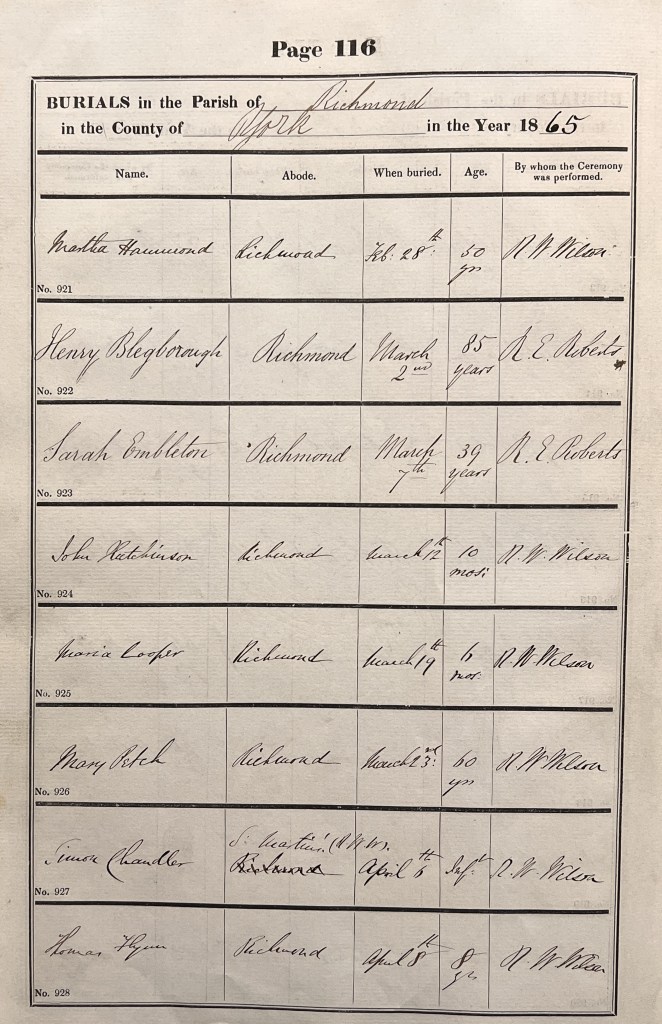

In the example of Sarah Embleton, whose interment was recorded in the parish burial register on 7 March 1865 (see below), a corresponding entry in the reference book to the churchyard plan (see above) tells us that she was buried in plot 169 (to the right of the south porch on the plan).

To have such a reference book within the parish record collection is unusual.

Postcard of Richmond, St Mary’s church [EF140/73]

The Cleveland Family History Society has transcribed the headstones within the churchyard of Richmond, St Mary and produced a list of these monumental inscriptions. This list can be viewed in our Record Office searchroom, or purchased in pdf format from the Society online.

Other records of burial

Great Ayton, All Saints: sexton’s notebook, 1846-1889 showing pages recording fees for setting gravestones &c, 1849 and descriptions of grave locations, 1878 [PR/AYG 7/34]

This simple note book shaped, rounded and polished from being kept in a pocket made from a rectangle of brown leather, covers folds of paper held in place with string. At one end, the sexton records marriage banns, when they were published and the date of the marriage. Turn it over and, from the other end, he records burials with the names, ages and cost of digging the grave. The sexton would have known all of the parishioners, and his descriptions of their burial positions show such respect and care:

- ‘South West of the steeple amongst friends’

- ‘Near the church gate feet to the hedge’

- ‘Betwixt his grandparents’

- ‘South of her husband close by’

- ‘Vault on top of his father’

Churchyard war memorials

Many parishes erected a war memorial to commemorate those who died in the First World War (1914-1918). These often took the form of a stone cross or obelisk bearing the names of those who died in the service of their country. Most of these memorials were erected by public subscription and some were placed in parish churchyards, such as the example from Masham below, which required a faculty authorisation to do so.

You can read more about war memorials in these related blogs.

Masham war memorial in the churchyard of St Mary’s church

Faculty authorising the placing of a stone crucifix as a war memorial in the churchyard attached to Masham church, 6 September 1920, listing the names of those to be remembered [PR/MAS 10/5]

Imperial War Museum webpage on the memorial at Masham, St Mary

Great Ouseburn war memorial in the churchyard of St Mary’s church

These images of Great Ouseburn, St Mary come from a collection of glass plate negatives from the early 1900s, taken by local photographer Louisa Krukenberg [EF 467]. You can read more about her photography in a related blog post.

Imperial War Museum webpage on the memorial at Great Ouseburn, St Mary

Further information

The Dunsforths Villages website provides a detailed history of the 1860s building programme of church (by Mallinson & Healey of Bradford), vicarage and school/school house in Lower Dunsforth, partly funded by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and partly by public subscription.

Borthwick guide to ‘Faculties and other records concerning the fabric of church buildings‘ (opens as pdf)