by Gwyneth Endersby, Archives Assistant

Introduction

December is the perfect time to look at some of the historic recipes we hold for an ever popular Christmas treat – mince pies. We’ll explore the origins of these pies and the kinds of ingredients used by bakers over time.

Within some of the collections we hold are several recipe books and loose recipe sheets (also known as receipts or receipt books). The majority are 18th- and 19th-century in date and, as may be expected, recipes for Christmas fare feature including plum puddings, Christmas cakes and mince pies.

Handwritten domestic receipt books are quintessentially personal, family items. Entries in different handwriting suggest that books were contributed to by different people over time, and the names of owners (with dates) might even be inscribed on the frontispieces. The recipes themselves might have annotated dates and the names of the source written alongside, whereas others might have no supporting information whatsoever. Handwritten recipe books can include heirloom recipes and those from friends and acquaintances, as well as popular dishes of the time copied from published cookery books.

Domestic receipt books

One small private collection [ZSQ] comprises six 18th– and 19th-century receipt books containing culinary, medicinal, and household recipes, as well as two inventories for Hornby Castle, and an account book. These items were owned (and possibly collected separately) by a physician with a particular interest in historical remedies and diets, and who apparently frequented an antique shop in Yarm in search of useful sources of information.

The collection of six 18th– and 19th-century receipt books containing culinary, medicinal, and household recipes, plus the marbled front cover of the book containing the mincemeat recipe [ZSQ]

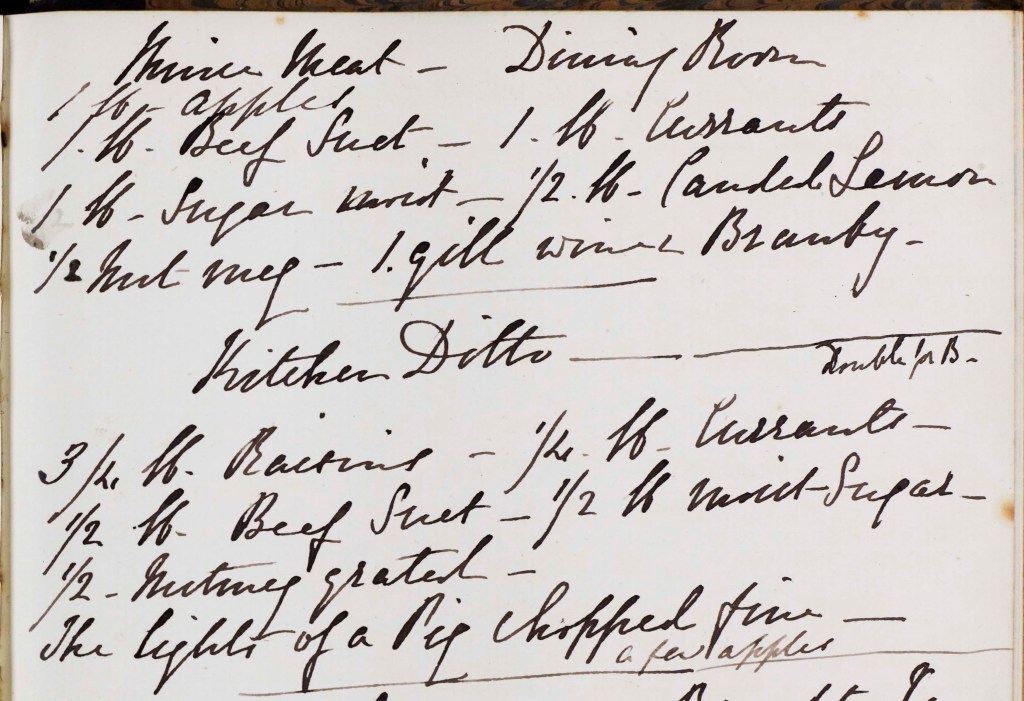

In one of the recipe books [ZSQ 8], the last recipe to appear is for mincemeat (see image below). It is itself undated but follows on from some soup kitchen recipes which are annotated 1862 and 1863, and a recipe title for treacle cake (but with no ingredients listed), dated ‘Nov. [18]67’. We’ve chosen to highlight it here as in fact two variations of mincemeat are given: an ‘upstairs’ dining room version – including lots of apples, candied citrus peel and plenty of brandy, and a ‘downstairs’ kitchen version – containing no alcohol or citrus peel, just a few apples and notably the chopped ‘lights’ of a pig. ‘Lights’ is another name for an animal’s lungs – a form of offal.

The kitchen version is very traditional, listing ingredients popular for centuries, whereas the dining room version illustrates the shift occurring in the mid to late nineteenth century towards making meat-free mince pie fillings.

Recipe for dining room and kitchen versions of mincemeat, from a personal recipe book (undated, but containing mid-19th century recipes) [ZSQ 8]

Below is a transcription of the recipe:

Mince Meat – Dining Room

- 1 lb Apples

- 1 lb Beef suet

- 1 lb Currants

- 1 lb Moist sugar

- ½ lb Candied lemon

- ½ Nutmeg

- 1 gill of wine brandy (¼ pint, or 150 ml)

Kitchen Ditto

- ¾ lb Raisins

- ¼ lb Currants

- ½ lb Beef suet

- ½ lb Moist sugar

- ½ Nutmeg, grated

- The lights [lungs] of a pig chopped fine

- A few apples

A brief history of mincemeat pies

Mincemeat pies in Britain can be traced back to at least the medieval period when spices and Middle Eastern cooking methods were reputedly brought into the country by returning crusaders. Mincemeat pies were in fact a variation of ‘sweet’ pies in general, whereby large cuts of meat or offal, beef suet, sugar, fresh and dried fruits, spices, and fortified wines or brandy were combined and baked in pastry cases. Minced pies, as the name suggests, required the meat to be chopped very finely. By the early 20th century, meat and offal had largely been replaced by apples and beef suet, and the sugar quantity was increased – a recipe more akin to the mincemeat we know today.

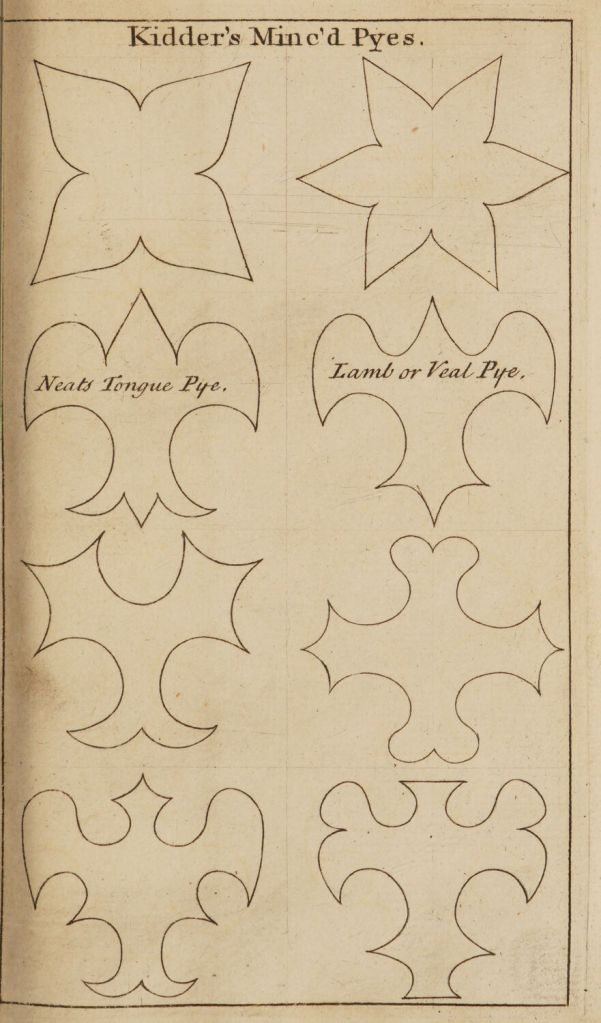

Originally minced pies were large showstoppers, baked in very elaborate shapes and with detailed pastry decoration. There are seventeenth- and eighteenth-century published cookery books which include drawings of pie designs to be used as templates.

Elaborate pie designs from Robert May’s receipt book: “The Accomplisht Cook, or the art and mystery of cookery” (1678), folded between pages 224 & 225. Images reproduced under Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Specific pie shapes or top decoration could be employed to denote a pie’s meat content (for example, neat’s [ox] tongue, duck, deer). Robert May 1588-c.1664) was a professional cook with over 50 years’ experience of catering for elite households.

Pie designs from Edward Kidder’s “Receipts of Pastry and Cookery, for the use of his scholars” (c.1720). J. Edward Kidder (1666-1739) was a writer and cookery teacher at his school in London during the 1720s to mid-1730s. Images reproduced under Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

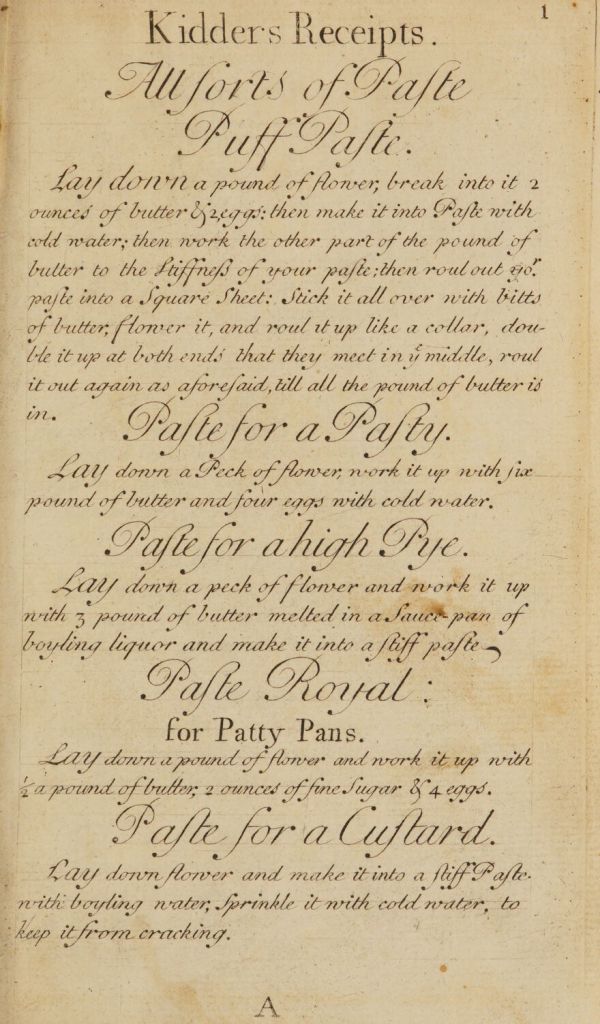

Different kinds of pastry were also employed, depending on the style and type of pie. Edward Kidder offers recipes for different kinds of ‘paste’ – pastry.

Kidder’s receipts for all sorts of pastry, and for sweet pies – including minced pies from “Receipts of Pastry and Cookery, for the use of his scholars” (c. 1720, pages 1 & 4). Images reproduced under Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Minced pies have long been associated with the Christmas period. Robert May’s book (1678) includes “Bills of Fare for Every Season”, listing minced pies as part of the first course in the extravagant menus for All Saints Day (Nov 1st)), Christmas Day and New Year’s Day, yet not at any other time of year.

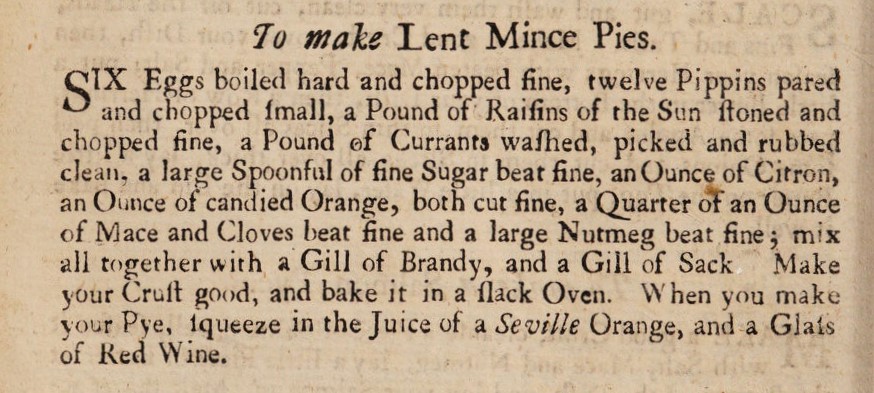

Hannah Glasse, however, in “The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy” (1751), does offer a recipe for Lent Minced Pies – laced with brandy, sack (sherry) and red wine, and with finely chopped hard-boiled eggs substituting the meat. Glasse (1708-1770) aimed her very popular book at the domestic staff of households.

Recipe for Lent Mince Pies, in “The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy: which far exceeds any thing of the kind ever yet published” (1751), detail from page 228. Image reproduced under Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Alongside home-made concoctions, commercial preparations of mincemeat were introduced by the Victorians, leading to increased popularity of mincemeat pies during the festive period.

Further reading:

“The Accomplisht Cook, or the Art and Mystery of Cookery. Wherein the whole Art is revealed in a most easie and perfect method, then hath been publish in any language.” By Robert May (1678 edition).

“E. Kidder’s Receipts of Pastry and Cookery, For the Use of his Scholars” (c. 1720 edition).

“The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy; which far exceeds any thing of the kind ever yet published” By a Lady [Hannah Glasse] (1751 edition).

Wikipedia webpage on Mince Pie

Wikipedia webpage on Mincemeat