by Sarah Pearey, Archives Assistant

This blog post explores documents issued from the royal Chancery held by North Yorkshire Archives. Documents issued from the Chancery, under the Great Seal of England, can generally be categorised into charters, letters patent, and letters close.

Charters, letters patent and letters close were issued to groups, individuals and communities across the country, whilst a record of each instrument was enrolled in the charter rolls, patent rolls and close rolls. These rolls are held by The National Archives, but all have been calendared and many made available online.

Charters

Royal charters were detailed legal documents that record a variety of grants in perpetuity (forever), including lands, honours and privileges. Charters may have been issued to make grants of lands and rights to lands; establish liberties to hold town markets; bestow peerages; create private corporations including towns and cities. Language used is very solemn, and the Great Seal will be attached at the foot of the document (pendent).

Charters were originally enrolled in the charter rolls from 1199. However, the charter rolls were abolished during the reign of Henry VIII, in 1517 – after that, documents that would be considered ‘charters’ are enrolled within the patent rolls.

The Giggleswick School charter, 1553

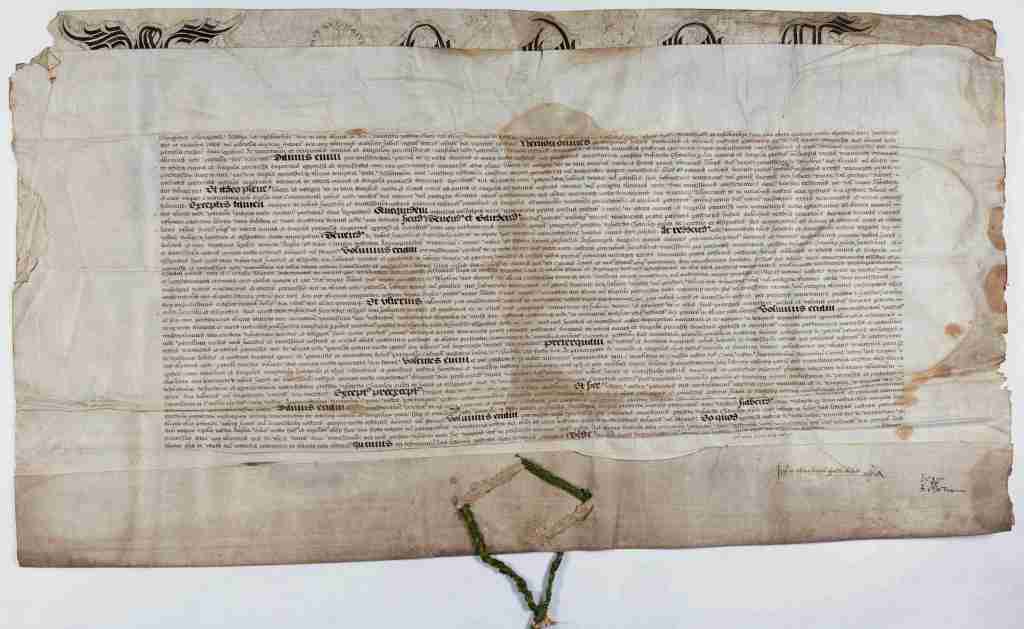

Giggleswick School charter, 1553 [S/GGW]

Giggleswick School was founded in 1499 but received its royal charter from King Edward VI in 1553, at the petition of John Nowell, vicar, Henry Tennant, gentleman, and other inhabitants of the town and parish. The charter granted land to the school and endowed it with the name The Free Grammar School of King Edward the VI of Giggleswick. It is one of around 80 schools in the country to have received a royal charter. Details of lands, rents and privileges granted to the school are recorded within the Patent rolls of Edward VI.

Letters patent

Letters patent often dealt with grants of land or rights from the monarch to a private individual, as well as conferring titles, appointments to office, licences, pardons, and protections. They were issued ‘open’, and the Great Seal was attached pendent at the foot.

Letters patent: licence to crenellate Bolton Castle

Licences to crenellate were grants issued for a building to be fortified. In medieval England, they were seen as a symbolic representation of lordly status – castellation could be considered the ‘architectural expression of noble rank.’

Letters patent granting license to Richard le Scrop’, the Chancellor, to crenellate his manor of Bolton in Wencelowedale (modern Wensleydale) or a place within it with a stone and mortar wall [ZBO I MC 55]

The contract for the building work at Bolton Castle (Castle Bolton, near Leyburn), 1378, between Sir Richard Lescrop and John Lewyn, mason, also survives [ZBO I MD 1]. It contains details of the embattled towers and chambers to be constructed.

Early charters and letters patent were generally plain and devoid of ornament, apart from in some cases where they were embellished with designs and even illuminated in gold and colour. This was done at the cost of the beneficiaries. Illumination was a practice that picked up in frequency from the fourteenth century.

These two letters patent, both issued under the reign of Richard II (1377-1399), illustrate the possible variety in decoration. The licence to crenellate is extremely neat, but the flourishes on the headline text are left empty [ZBO I MC 55, see above] – unlike in the letters patent, granting pardon to Elizabeth and John Dawnay, which features an emblem of a saint, and images of dogs, a snake, and a man in the headline text [ZDS II 1/1, see below & page header image].

Letters patent of Richard II granting pardon to Elizabeth Dawnay, née Newton, John Dawnay and others on account of their trespass of alienating without licence one third of the Soke of Snaith. Incorporating settlement on Elizabeth and heirs by Thomas Dawnay, 12 February 1391 [ZDS II 1/1]

This document is granting pardon to Elizabeth Dawnay and others – it appears that they sold land on the Soke of Snaith without receiving a licence to alienate (another form of letters patent which allowed owners of manors to sell them).

Over time, extravagantly decorated letters patent became more common. By the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547), initial portraits of the monarch became commonplace (though completed in varying detail and skill). Margins may also feature heraldic insignia, scroll work, foliage and other decoration in ink. This was largely dependent on how much the beneficiary was willing to spend.

Letters patent of King Henry VIII granting to Richard Cholmley the manors of Eskdaleside and Ugglebarnby, formerly in the possession of Whitby Abbey, 1 March 1546 [ZCG I]

Many later letters patent of Henry VIII grant lands formerly in the possession of monasteries, which had been confiscated under the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Letters patent creating Charles Powlett, Marquess of Winchester, Duke of Bolton, 8 April 1689 [ZBO VIII]

In this letters patent, Charles Powlett, Marquess of Winchester, is made Duke of Bolton by King William after having supported the claim of William and Mary to the throne – and appears to have gone to considerable expense to have the document decorated with heraldry, gilt lions and foliage, and a painted initial portrait of King William [ZBO VIII].

Below is a selection of four initial portraits of monarchs from letters patent in our collections:

Letters close

Whilst letters patent were public proclamations of a grant, pardon, licence, etc, letters close gave orders and instructions to individuals. The information was not necessarily confidential, but the original letter was sealed and folded – closed – unlike letters patent, which were issued ‘open’. Letters close issued under each monarch were recorded in the close rolls from 1204.

The original letters are much rarer in archive collections today than are letters patent, and they usually don’t retain their seals.

Letters close from Queen Elizabeth I to Sir William Fairfax, formerly Sheriff of Yorkshire to deliver his charge to the new Sheriff, 17 November 1578 [ZQG(F) 2/1]

The Great Seal

What charters, letters patent and letters close all have in common, is that they were issued under the Great Seal. The Great Seal attached to these documents was the essential means of authenticating acts of the monarch and their government. From the time of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), the custodian of the Great Seal was the Chancellor. Under the Chancellor was a large staff of clerks who made up the English royal Chancery and prepared the instruments (documents) which were to issue under the Great Seal.

All Great Seals of English monarchs were derived from that of Edward the Confessor – circular and double-sided, with a diameter of about three inches. William the Conqueror’s seal (1066-1087) had a majesty (royal) side, enthroned, and an equestrian (baronial) side. This design was retained by successors until it was replaced by the Commonwealth in 1649 with a map of Britain and depiction of the Commons in session. Charles II (1649-1685) reintroduced the traditional majesty/equestrian imagery in his Great Seal. Several examples of Great Seals in our collections are illustrated below.

Sources and further reading:

Pierre Chaplais, English Royal Documents, King John – Henry VI, 1199-1461, 1971, Clarendon Press.

Philip Davis ‘English Licences to Crenellate 1199-1567’, in The Castle Studies Group Journal, No 20 (2006-7)

Sir H.C. Maxwell-Lyte, Historical notes on the uses of the Great Seal of England, 1926, HMSO.

The National Archives research guide webpage: How to look for records of…Royal grants in letters patent and charters from 1199

The University of Nottingham webpage: Letters patent