by Joanne Faulkner, Record Assistant

North Yorkshire Archives holds large collections of the estate and private records of some of the most significant and influential families in the United Kingdom. Many of these families are ancient and can trace their lineage to the medieval period.

In some collections, these genealogies are recorded in pedigrees. These hand-drawn, often coloured and sometimes illustrated records are undoubtedly treasures of these collections. They are some of the largest documents held at North Yorkshire Archives, the longest measuring over 5 metres in length.

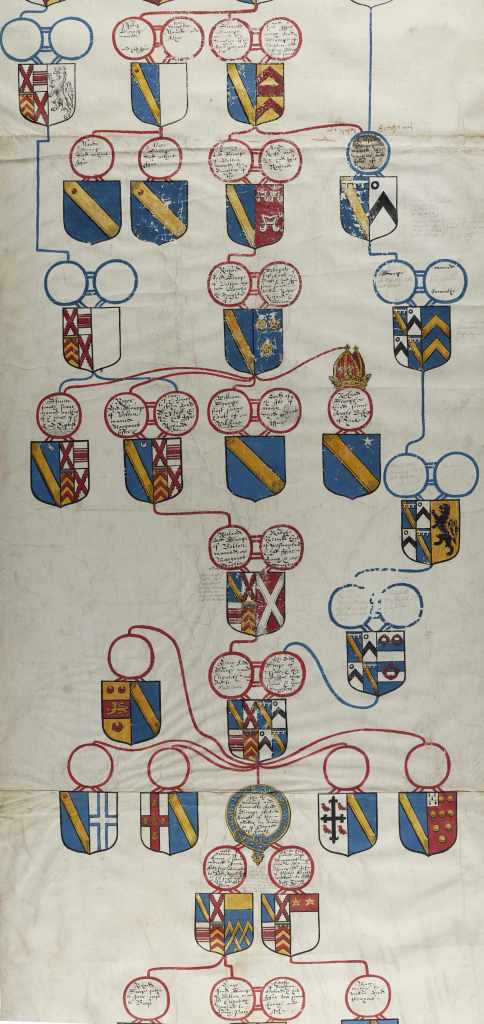

Pedigree from the Darley of Aldby archive (left), with detail of the upper part [ZDA/DAR FP3]

Section of the Scrope pedigree, c. 17th century, with later additions [ZPT 25/1]

The Scrope pedigree above shows an unbroken line from William the Conqueror to the 17th century, when it is thought that this pedigree was drawn. The name Scrope is Norman in origin. The family seat was originally at Bolton Castle in Wensleydale.

Having pedigrees drawn up would involve time, skill and expense. There were various reasons for commissioning them. One of the most common reasons for drawing up pedigrees was to determine right to inheritance of title or property. They were important family records throughout generations, and it is likely that this legal function is a major factor for the preservation and survival of these documents.

The roots of recorded genealogy through heraldry, can be traced to the establishment of the College of Arms. The Heralds originally recorded the arms displayed by knights at tournaments. After such tournaments declined the use of heraldry continued in civilian use. Throughout most of the 17th century Heralds examined gentleman’s claims to the right to bear arms and could verify or reject their claims. Pedigrees could be drawn as part of this process.

Illustrations from the Babington pedigree, part of the Clifton Castle archive [ZAW 17/6]

Recording pedigrees became particularly popular during the 19th century, when the growing middle classes and nouveau riche wished to prove links to established aristocracy. The right to a coat of arms may be confirmed by a senior Herald of the College or Arms (called a King of Arms) and a new grant of arms may be conferred by them under Crown authority. A private registration of arms does not create any legal right.

Heraldry and coats of arms

Though the rulers and warriors of various ancient societies adopted their own personal symbols, coats of arms as we recognise them have their origins in the world of medieval knights.

The identification of knights both on the battlefield and at tournaments required bold colours and symbols. An easy visual means of identification was necessary, particularly where the closed helmet was worn for protection.

Illustration from the Fairfax Pedigree [ZDV (F)]

The Fairfax pedigree shows the Fairfax family line from the early 13th century when the Family seat was at Walton in Ainsty. It includes the Maltby and Etton family lines. The Fairfax family is known for its close association with the English civil war. While many Yorkshire families sided with the King, Sir Thomas Lord Fairfax was a Parliamentarian and in 1645 was appointed Commander in Chief of the New Model Army.

When heraldry began, the bearer himself was part of the image. He carried his shield, painted in his colours, wore his crest on his helm and may have carried a surcoat decorated with symbols. The heralds who organised tournaments would advise on suitable designs. Over time, nobles ceased to employ heralds and only those of the royal household remained. Heralds became solely concerned with the granting and authentication of coats of arms under the authority of the Sovereign.

Heraldry is properly defined as the system by which coats of arms are devised, described, and regulated. Arms are described using very specific terminology for the colours, shapes, symbols and positioning of elements of the design.

Coats of arms are used in pedigrees to show descent through families. Arms are hereditary and pass from the armiger (one who has been given the right to bear a coat of arms) on their death, to their heir in the male line. While the armiger lives all sons must add differences to their arms so that they are distinct. Unmarried women and widows bear arms in a diamond shaped lozenge, without any military or masculine features.

Grant of arms: Maynard – Grant of 1785 allowing Sarah Lax, widow of John Lax of Eryholme, and her heirs, to take the name and bear the arms of Maynard. Sarah was a descendent of John Maynard of Kirklevington. This design features the lozenge shape typically found in female arms [Z.26/1]

Grants of arms were presented and kept in bespoke tooled leather cases, indicative of the importance and authority of the document within. The case above is shaped in the form of the deed and seals. It is lined with handmade paper. The wax seals are protected inside painted tin enclosures.

Grant of arms: Darley – Grant to Richard Darley of Buttercrambe in the parish of Bossall, dated 10 April 1583 [ZDA/DAR FP5]

Darley was one of the gentlemen of the North Riding declared fit to lend the queen £25 in the Armada year of 1588.

Detail from grant of arms: Rowland Lee – illustration of arms from a certificate by Thomas Benolt, Clarencieux, granted to Rowland Lee, Bishop elect of Coventry and Lichfield [ZDV XI 1533]

Rowland Lee held considerable power, serving as ‘Lord President of the Marches’. He is believed to have performed the marriage ceremony of Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn.

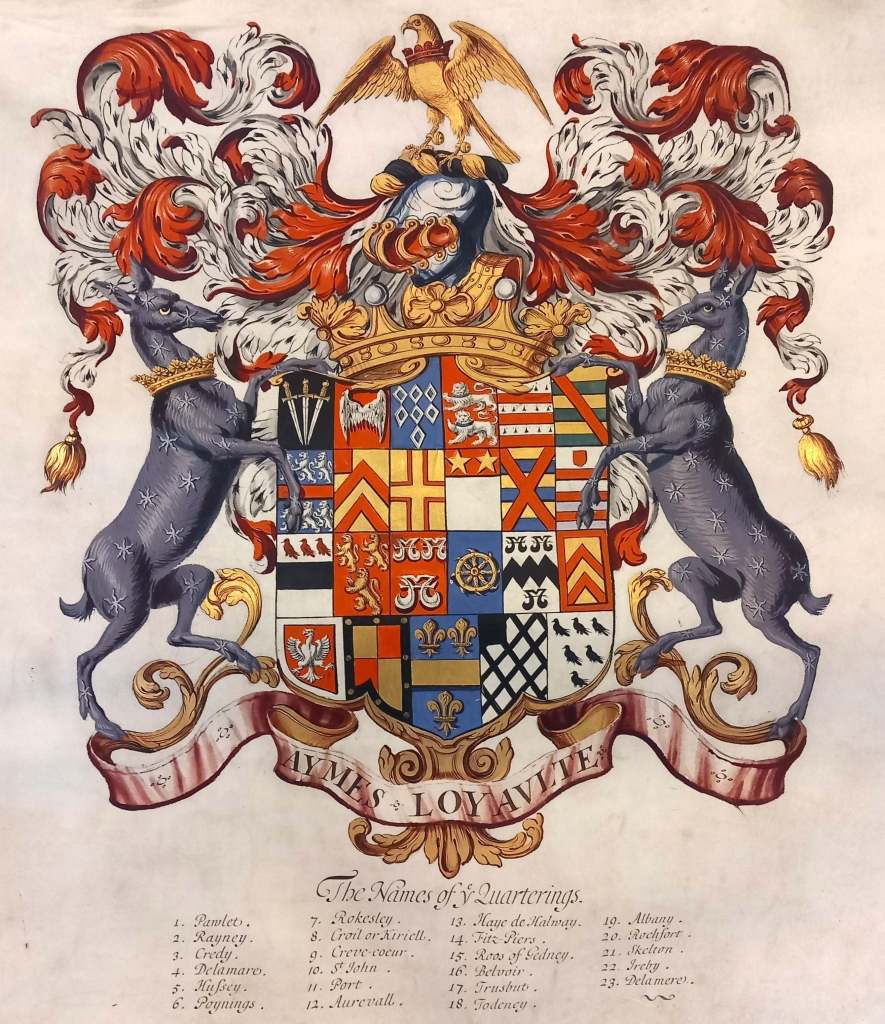

The full display of all devices to which the armiger is entitled is called an ‘achievement of arms’. This often features at the bottom of a pedigree.

‘Achievement’ from the Pawlett pedigree: the pedigree of the Pawlett/Paulet family, believed to have been drawn by the College of Heralds [ZBO]