by Katherine Bullimore, Record Assistant

Every record tells a story; the North Riding Quarter Sessions’ records tell many stories that can be embarrassing, shocking or tragic, and our online catalogue can be used to help discover some of these. Following on from previous posts about the North Riding Quarter Sessions, this blog explores further examples of offences committed and the penalties that were imposed.

“Opening the documents is like reading the story line of a modern ‘soap’ and over the years the rogues of the community emerge.” Quarter Sessions’ volunteer

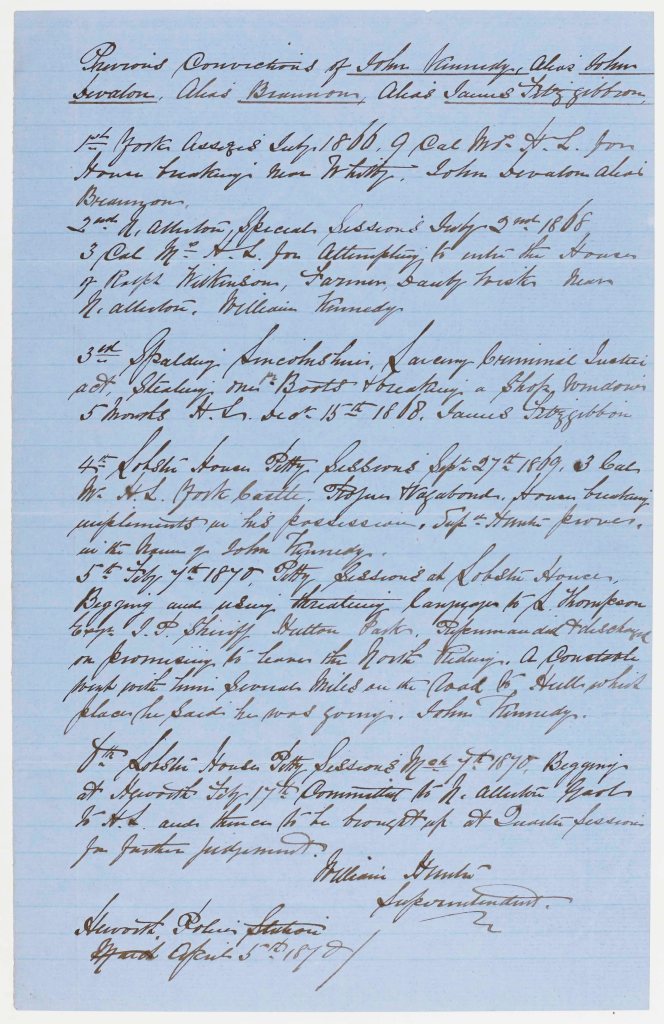

One such rogue was John Kennedy, described in North Riding Quarter Sessions’ documents as an ‘incorrigible’. He was arrested at Haxby in 1869 with housebreaking tools, threatened the magistrate who committed him to York Castle, and was later arrested again at Sheriff Hutton for trying to exhort money and threatening to blow the place up with gunpowder! He had several aliases and previous convictions for theft and house breaking at Whitby, Northallerton and Spalding in Lincolnshire [QSB 1870 2/9/3].

Notes dated 4 April 1870 relating to John Kennedy, ‘an incorrigible rogue‘ [QSB 1870 2/9/3]

While there are many cases of theft, housebreaking, assault and similar offences, the range of cases in the Quarter Sessions extends much more widely. Some cover actions that are no longer crimes, others reveal ongoing abuses in urgent need of reform, and some seem strikingly familiar, revealing ways in which the past resembles the present.

Old offences in the North Riding Quarter Sessions

Some North Riding Quarter Sessions’ indictments were for things we would not view as wrong at all today. For example, in the seventeenth century, church attendance was compulsory. The Quarter Sessions’ document below, written in Latin, dates from 1690 and indicts a large number of people aged 16 or older for not attending church within the last six months [QSB 1691 6/10].

Bill of indictment: various inhabitants of several parishes for not having attended their parish church within the last six months, offence committed on 24 August 1690 [QSB 1691 6/10]

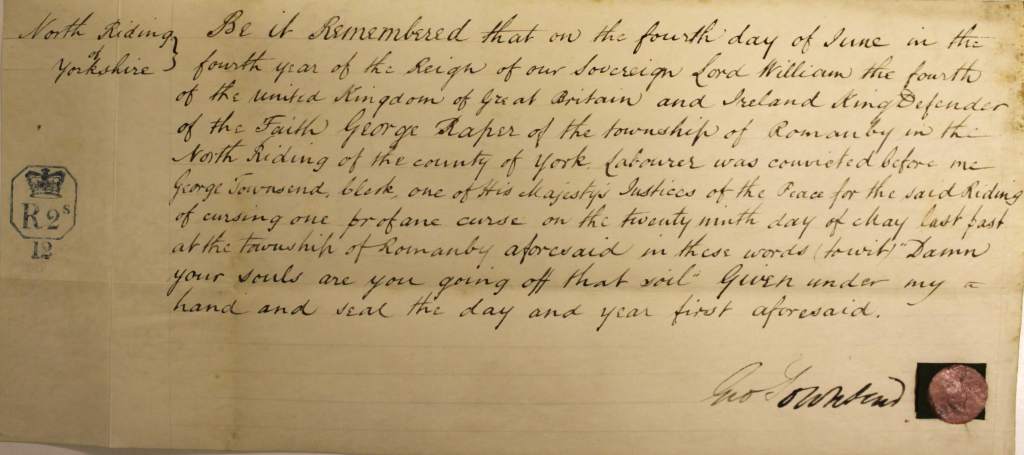

George Raper, labourer of Romanby, might well have been annoyed at his summary conviction in 1834 for using a ‘profane curse’ which is quoted as ‘Damn your souls, are you going off that soil’. He was ordered to keep the peace [QSB 1834 3/10/12].

Summary conviction of George Raper of Romanby for using a profane curse, saying ‘Damn your souls, are you going off that soil’, offence committed on 29 May 1834 [QSB 1834 3/10/12]

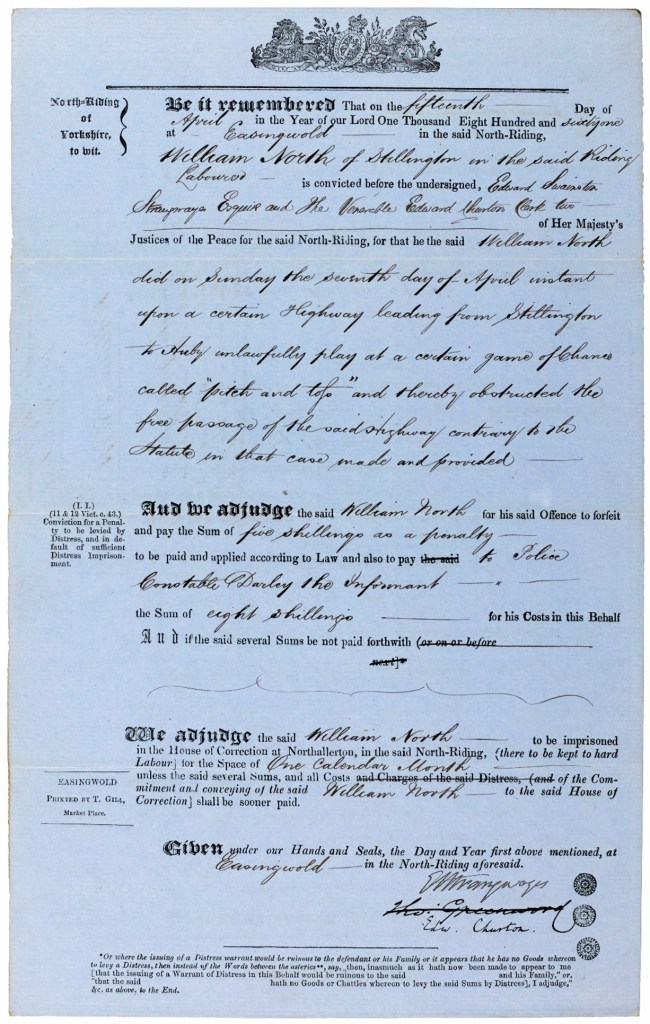

This summary conviction of William North of Stillington, in 1861, states that he had:

“upon a certain Highway leading from Stillington to Huby unlawfully play at a certain game of chance called “pitch and toss” and thereby obstructed the free passage of the said highway” [QSB 1861 3/10/4/16].

Summary conviction of William North of Stillington for obstructing the highway leading from Stillington to Huby by playing a game of chance called pitch and toss there, offence committed on Sunday 7 April 1861 [QSB 1861 3/10/4/16]

Four other men were convicted with him and each of them was given a fine of 5 shillings for the offence and 8 shillings in court costs. Pitch and toss is a game where you throw a coin and try to land as close as possible to a mark, the person who gets closest keeps the coins.

Child support in the North Riding Quarter Sessions

Discovering an illegitimate ancestor can be a dead end to those researching family history. However, parishes were often very concerned to establish who had fathered illegitimate children, so they could extract payment for them – child support in modern terms – and records of such cases can be found in the Quarter Sessions. If the father could not be found, the parish would usually have to pay for the support of the mother and baby, and parishes much preferred to make the father support his child.

John Plummer of Burton Leonard in the West Riding, weaver, was charged in 1809 with being the father of the unborn child of Mary Meggison of Osmotherley [QSB 1809 1/11/11].

Bastardy recognizance relating to the child of Mary Meggison of Osmotherley, 3 November 1808 [QSB 1809 1/11/11]

The Osmotherley parish register shows the baptism of Elizabeth, daughter of Mary Megginson on 30 April 1809, with no name given for the father, so the Quarter Sessions’ document above is the only evidence that she was said to be John Plummer’s daughter [PR/OSM 1/3].

Extract from the Osmotherley baptism and burial register, 1789-1812, recording the baptism of Elizabeth, daughter of Mary Megginson on 30 April 1809, with no name given for the father [PR/OSM 1/3]

These cases were so common that forms were printed which could be filled in by hand with details of names and dates. George Smailes of Cornborough, husbandman, here gives surety to appear at the next Quarter Sessions to answer a statement given by Frances Foster of Sheriff Hutton, singlewoman, that he is the father of her unborn child [QSB 1809 1/11/1].

Bastardy recognizance relating to the child of Frances Foster of Sheriff Hutton, 23 August 1808 [QSB 1809 1/11/1]

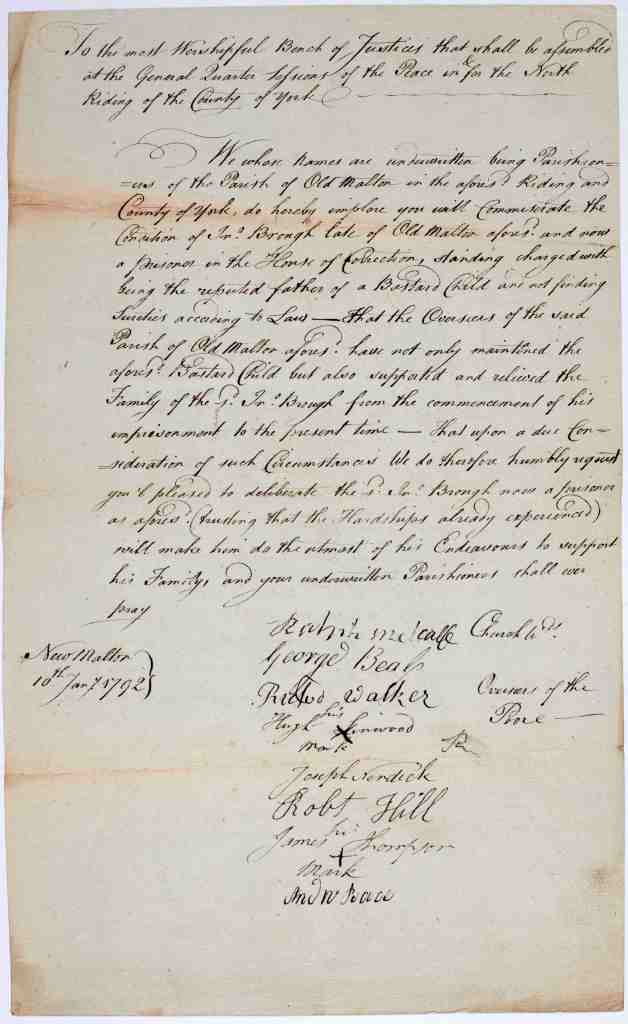

Failure to pay child support had stern penalties. In 1790, John Burgh or Brough was imprisoned in the House of Correction, Northallerton for ‘disobeying an order for the maintenance of the bastard child of Hannah Wardel of Old Malton’.

In 1791, George Watson, apparently a Malton official, stated he had no intention of freeing Brough:

“I don’t know one single circumstance in his favour … He is a person of whose course of life I have the worst opinion.”

Early in 1792, eight Old Malton parishioners wrote to ask for Brough’s release saying that since his imprisonment the parish had had to maintain Brough’s family. They hoped ‘that the hardships that he has experienced will make him do his best to support his family’ – in short, freeing him might save the parish money! This petition seems to have worked, as Brough is not found in later lists of Northallerton prisoners [QSB 1792 1/9/17].

Petition relating to John Brough, late of Old Malton, 10 January 1792 [QSB 1792 1/9/17]

Smallpox offenders in the Quarter Sessions

Late-19th-century Quarter Sessions’ records show determined attempts to combat the infectious disease of smallpox and legal penalties for those that failed to do so. Smallpox was deadly and much feared, about 30% of those who caught the disease died. There are parallels to be drawn with recent lockdown regulations introduced to combat COVID-19, and the penalties for those who broke them.

In 1852, a law was passed that all children should be vaccinated against smallpox within three months of their birth. Parents who failed to do this were fined. A number of such cases are recorded in the Quarter Sessions.

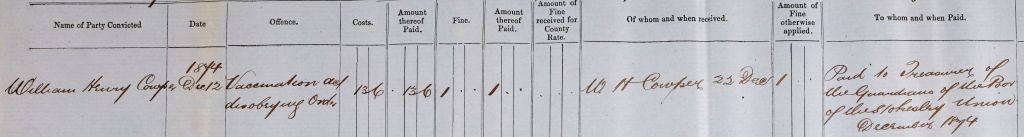

William Henry Cowper of Marton, secretary to the ironworks, was convicted for failing to have his son, Frederic William Cowper, vaccinated and ignoring a previous order to have him vaccinated. He was fined one pound, plus thirteen shillings and sixpence costs. The document below shows he paid the fine immediately [QSB 1875 2/10/9/4].

Summary conviction of William Henry Cowper of Marton for failing to have his son Frederic William Cowper vaccinated against smallpox, 12 December 1875 [QSB 1875 2/10/9/4]

The document below is a summary conviction of John Close of Middlesbrough, grocer, for failing to take proper precautions against the spread of smallpox on Northallerton railway station when he was in charge of William Ambrose Barnitt of Middlesbrough who was suffering from the disease [QSB 1871 3/10/1/4].

Summary conviction of John Close of of Middlesbrough for exposing William Barnitt, who was suffering from smallpox, on Northallerton railway station without proper precautions against spreading the disease, 13 April 1871 [QSB 1871 3/10/1/4]

We do not know why Close was in charge of Barnitt, but the penalty was a severe one. He was fined five pounds, plus one pound and nine shillings in costs, which was a substantial sum in those days and, if he did not pay, he was to be imprisoned for three months with hard labour.

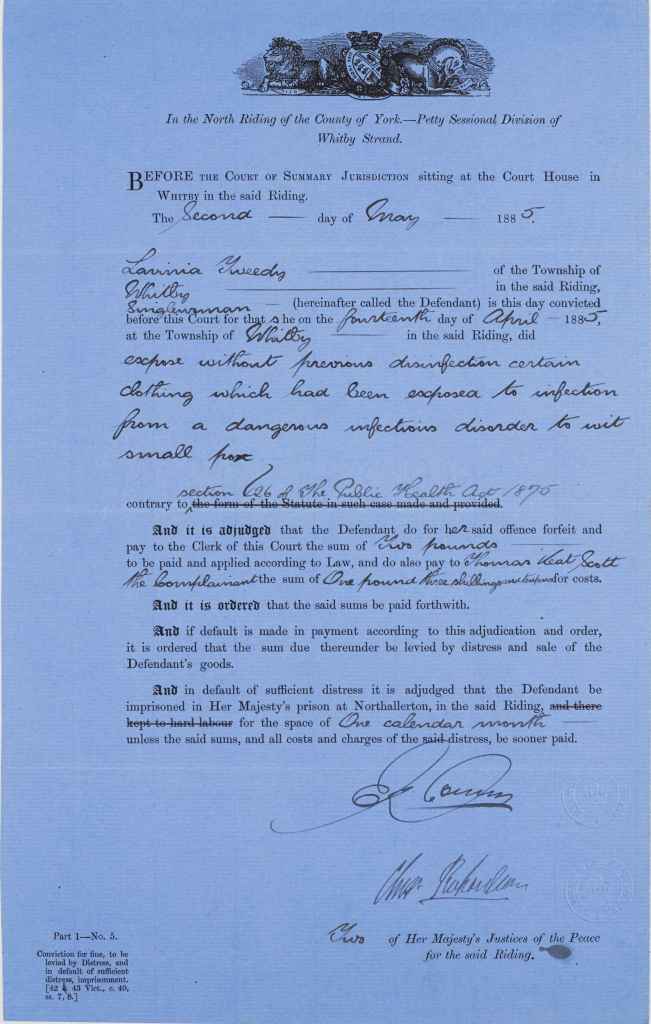

Even the handling of clothing which had been in contact with a smallpox sufferer was regulated. Lavinia Tweedy of Whitby, singlewoman, was convicted for exposing without disinfection clothing which had previously been exposed to infection by smallpox. She was fined two pounds plus costs, with the sum to be raised by seizure and sale of her possessions if she did not pay [QSB 1885 3/10/11/30].

Summary conviction of Lavinia Tweedy of the township of Whitby singlewoman for exposing without previous disinfection clothing which had been exposed to infection by smallpox, 2 May 1885 [QSB 1885 3/10/11/30]

The strict measures taken against smallpox were successful, not only in Britain but worldwide. The disease was declared extinct in 1980.

Dickens and ‘defamation’, Nicholas Nickleby foreshadowed in the Quarter Sessions

In 1809, a Bowes schoolmaster called John Adamthwaite indicted two labourers at the Quarter Sessions for making ‘defamatory’ poems about him, essentially a charge of slander. Astonishingly, the small village of Bowes and its surrounding area was home to as many as twenty boys’ boarding schools in the early nineteenth century. These private schools had very bad reputations, but the practice continued for decades. In 1838, Charles Dickens came to Bowes to investigate its schools, with the intention of drawing attention to the abuses which went on there by putting them in his third novel, Nicholas Nickleby. William Shaw, one of the Bowes schoolmasters of the time, is said to have been the model for Dickens’ villain Wackford Squeers, although Dickens himself wrote that Squeers is ‘the representative of a class, and not of an individual’, he also claimed his portrayal of school conditions in the novel was not invented. The building which once housed Shaw’s school is now known as Dotheboys Hall after the school in Dickens’ novel.

Photograph of ‘Dotheboys Hall’, Bowes taken by Bertram Unné, 2 January 1973 [BU03074]. This image was commissioned for the first ever Ilkley Book Festival.

By bringing indictments at the Quarter Sessions, John Adamthwaite left a record of what locals thought of him and his school, for both the poems are recorded in full.

The poem by Robert Lamb concentrates on conditions at the school [QSB/1809 2/6/10]:

“Two lodging rooms in Pompey’s house there are

Where boys are cramm’d up as the sick in war

A putrid smell our nose doe quick assail

Enow to give disease, make you bewail

The cursed time you saw these dungeons drear

Where boys condemn’d there shed many a tear

For beds they better lie on the boards

Or on the ground like savages in hordes

A ragged blanket and a tatter’d sheat

A quilt alas with lops it’s almost eat

Is all they have to keep them from the cold

Unhappy wretches to slavery you’re sold

In wintertime you almost naked go

And shiver in the piercing frost and snow

Hard is your lot for victuals they are scant

Your mournful theme is a perpetual want

Boys rise!! Revenge!! Beware you’re not too late

And hunch that rascal you so justly hate

His cunning words they glitter all without

But know within they’re filthy as the gout

Down with the tyrant and then you all may cry

Success brave boys you’ve gain’d your liberty!!!!“

Cover of the 1st edition of Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby [public domain via Wikimedia Commons]

The poem by William Bell is a personal attack on Adamthwaite and his wife [QSB 1809 2/6/11]:

“In Bowes there is a boarding school of great and mighty state-O

Kept by a pompous prideful king, its name is A[damthwai]te -O

I’m sure for shape with him Pompy* compare you can but very few-O

He has a hump upon his breast, on his back a bumping clew-O

His wife likewise a peevish elf who grins and scolds for ever-O

Is just composed of skin and bones, of flesh faith she had never-O

From noble blood perhaps he sprung, perhaps of mighty fame-O

His mother from the work house came to raise his might-O“

* ‘Pompey’ seems to have been a local nickname for John Adamthwaite.

A nineteenth-century illustration from Nicholas Nickleby: ‘The first class in English spelling and philosophy.’ [CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons]

Robert Lamb’s poem is particularly interesting because it gives a local description of a school in Bowes which is strikingly similar to the one Dickens would give years later. Defenders of Bowes Schools, at the time and later, have suggested the schools were not as bad as claimed, merely rather austere by middle-class London standards. Lamb’s poem shows it was not only outsiders who thought the schools were grim. Adamthwaite may have been unpopular with the locals for other reasons, but it is still revealing that a labourer like Lamb thought the conditions were shocking.

It is very unlikely that Dickens knew Lamb’s poem, but the last lines foreshadow the boys’ uprising that happens at the end of Nicholas Nickleby. In real life there was no uprising, but the public backlash that followed the publication of Nicholas Nickleby put an end to such schools. John Adamthwaite did not live to see it, having died in 1817.

Previous blog posts on the North Riding Quarter Sessions:

- Introducing the Quarter Sessions and those who attended: All Human Life: North Riding Quarter Sessions, 1660-1971

- The various types and subjects of the Records of the North Riding Quarter Sessions

- The Working papers of the North Riding Quarter Sessions

- Juvenile offenders in the North Riding Quarter Sessions

- Previous blogs on stories of criminal women who appear in North Riding Quarter Sessions’ records