by Sarah Pearey, Record Assistant

Introduction

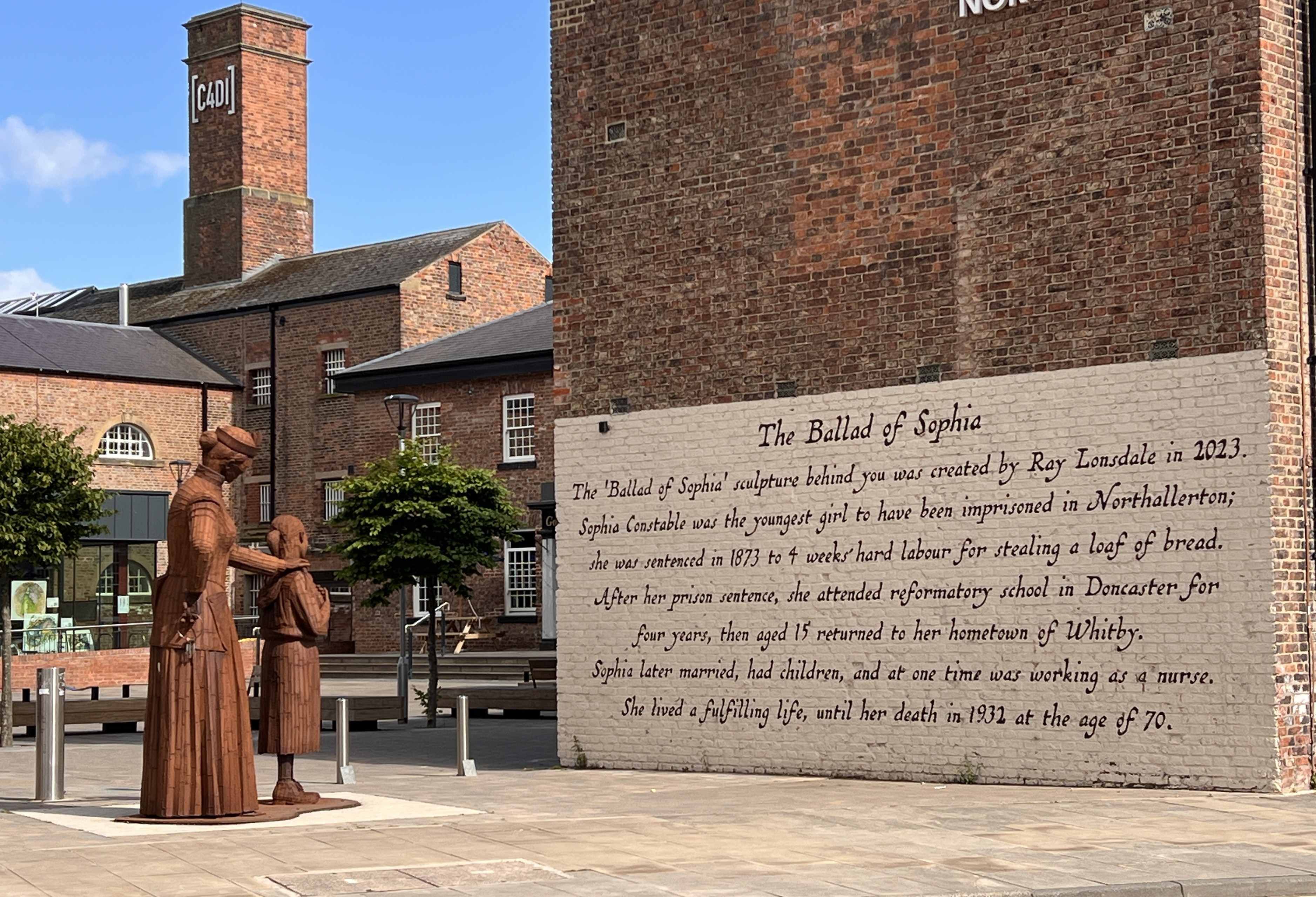

This article is the product of research into the North Riding Quarter Sessions records, as well as census and parish registers, by many at North Yorkshire Archives over the years, particularly to trace the lives of some of the younger faces that appear in the late-19th-century Police charge book of early mugshots [QP]. Sophia Constable, the youngest female recorded as an inmate at the old Northallerton Prison, has been of particular interest, and has recently been immortalised in a 1.5x life-size statue by Ray Lonsdale on the site of the old prison, now the Treadmills Development in Northallerton.

Ray Lonsdale’s 2023 steel sculpture ‘The Ballad of Sophia Constable’, commissioned for the new Treadmills Development on the site of the former Northallerton Prison, East Road, Northallerton. The sculpture depicts Sophia clutching a loaf of bread, with a prison warden placing a hand on her shoulder [photographs by Gail Falkingham, May 2025]

Sophia Constable… a sorry start

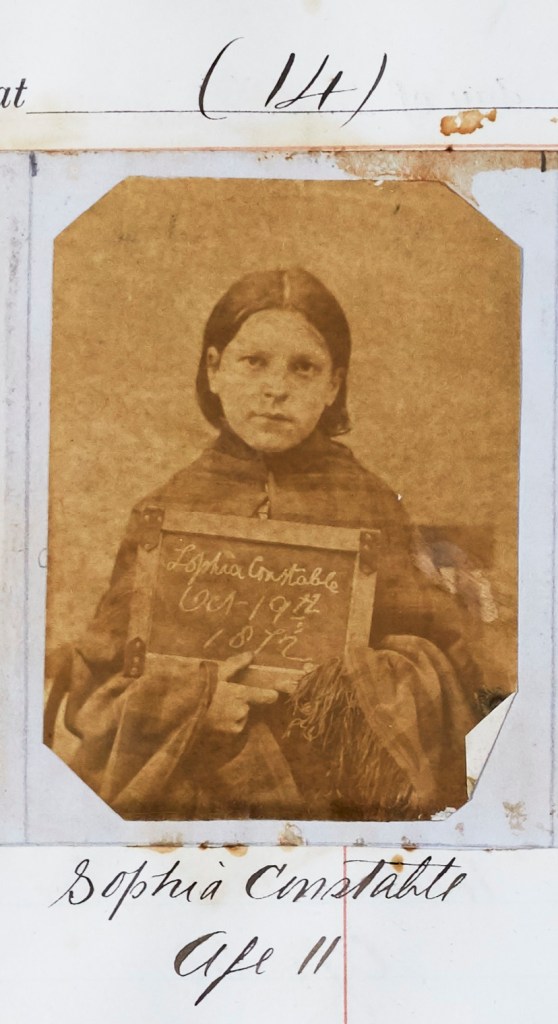

Photograph of Sophia Constable, age 11, in the Police charge book, 19 October 1872 [QP]

Sophia Constable was born in Whitby on 2 February 1862. On her birth certificate, her mother is listed as “Elizabeth Fox, formerly Constable,” and father as Thomas Fox. However, there is no evidence of Elizabeth having married a Thomas Fox. By the 1871 census, Sophia was living on New Way Ghaut, Whitby with her mother and brother, George. Her mother is recorded as a fish dealer and unmarried.

The next we hear of Sophia Constable relates to her offence committed on 12 October 1872. It is reported in the Whitby Gazette:

“Fanny Goodchild (20) and Sophia Constable (11) were charged with obtaining a loaf of bread from Francis Mackintosh, by false and fraudulent pretences, on the 12th inst. Mrs Macintosh said her husband keeps a provision shop in Church-street. On Saturday night the younger prisoner came for a cake, saying it was for Mrs John Gallilee, of Sandgate. Witness had not a cake, and she sent a three-penny loaf. Mrs Gallilee was in the habit of sending for bread, but she had up to this time sent the money, and she let the prisoner have it, thinking she was a fresh servant of Mrs Gallilee’s. When she left the shop she thought it strange the money was not sent as usual, and told her husband to see where prisoner went. -Thomas Macintosh said he saw Constable join another girl in Ellerby-lane. They went down the lane, and he lost sight of them in Sandgate. He went to Mrs Gallilee’s, and she said she had not sent anyone for a cake. Ann Gallilee deposed that she had never spoken to prisoners, and had consequently never authorised them to get any bread for her.” from the Whitby Gazette, Saturday, 26 October 1872

Sophia was apprehended by Superintendent Ryder near her home on the Friday afterwards; he later arrested Fanny Goodchild. They were committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions to be held in January 1873.

Prior to the trial, in a letter addressed to Captain Gardner, Justice of the Peace, arresting officer Superintendent John Ryder states that Sophia’s mother is a convicted thief and a prostitute. He describes their house as a “most wretched place,” with no furniture or beds, where all sleep on the floor, and nearly starve in winter.

Letter from Superintendent Ryder of Whitby to Governor Captain Gardner (Northallerton) regarding the home life of Sophia Constable [QSB 1873 1/9/1]

Ryder declares that:

“The best thing that can be done is to send the girl to the Reformatory School – if she is allowed to come back, there is nothing to save her from turning out to be a prostitute or a thief.”

At the Epiphany Quarter Sessions, January 1873, Sophia and Fanny are tried and convicted for felony. When asked to answer to the charges, Sophia had nothing to say, but Fanny responded:

“I shouldn’t have sent for the loaf if I hadn’t been hungered.”

Gaol and reformatory school

Sophia was sentenced to three weeks of hard labour at Northallerton Gaol, to be followed by 4 years at a Reformatory School.

Fanny Goodchild and Sophia Constable in the Calendar of Prisoners for Northallerton House of Correction, 1873 [QSB 1873 1/5]

Little is currently known about Sophia’s time at reformatory school, however, evidence has been found of her being at the West Riding Girls’ Reformatory in Doncaster, from the North Riding Quarter Sessions’ bills and vouchers [QFA(B)]. The North Riding did not have a girls’ reformatory in operation at that time.

An account of contributions payable towards the maintenance of girls sent from the North Riding to the West Riding Reformatory for Girls, Doncaster, quarter ending 30 September 1873. Third on the list is Sophia Constable [QFA(B)]

By the time of the 1881 census, Sophia was back at New Ghaut Way, living with her mother (now Elizabeth Mennell), her step-father, and three siblings. Sophia had also had a daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, in late 1879, to an unrecorded father.

In 1888, Sophia is married to John Leppington, both being listed as from New Way Ghaut. Sophia is able to sign her name on the marriage register very legibly – unusual for a woman of her standing at the time. She may have been taught to write during her time at the Reformatory.

Marriage entry for John Leppington and Sophia Constable, 1888 in the St Mary’s church, Whitby parish register. Interestingly, Sophia’s father is recorded as Thomas Constable, a horse-dealer. This is the only record with this name [PR/WHI 1/39]

In the 1891 census, John and Sophia are still living at New Ghaut Way, Whitby, a couple of doors down from Sophia’s mother. The 1891 census shows Sophia’s daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, residing at the Yorkshire Institution for the Education of Deaf and Dumb Children, Doncaster. Her entry on the admission register lists her mother, Sophia, as a nurse [admission registers from 1844-1905 are held at the City of Doncaster Archives].

In the 1901 census, Sophia and John still lived on New Way Ghaut, Whitby, now with Sarah Elizabeth, who was a dressmaker. In 1904, John and Sophia had a baby boy, named John George Leppington. In 1932, Sophia died and is buried in Whitby. There is no evidence to suggest Sophia was ever again in trouble with the law.

Northallerton House of Correction

Northallerton House of Correction may seem like a harsh place for a pre-teen, but whilst Sophia Constable may have been its youngest female prisoner, the gaol was not unused to the sight of juvenile offenders. Thrteen, fourteen and fifteen year olds regularly appear on its Calendars of Prisoners from the nineteenth century.

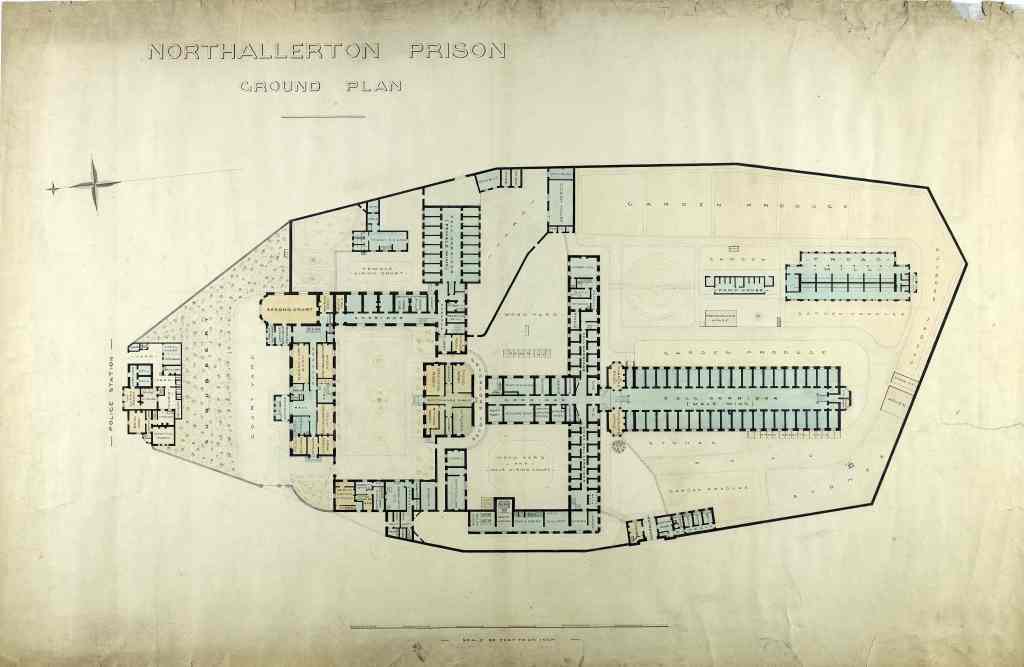

Northallerton House of Correction Gaoler Reports, and the ground plan from the mid-nineteenth century (see below), show that men and women were housed in separate wings, but there was no separate area for juveniles. The prison did employ a schoolmaster and had rooms for a schoolmistress.

Northallerton Prison ground plan, undated [c. mid-19th century [QAG]]

Convicts, including juveniles, could be sentenced to hard labour of the first class, consisting of work at the tread mill, crank or stone breaking. Hard labour of the second class included tasks like oakum picking, wood chopping, smiths’ and carpenters’ work. Second class for female prisoners included washing and ironing, sewing and knitting, and cleaning the yards of the female prison.

Other punishments commonly administered to children were solitary confinement and whipping. By the 1890s, at Northallerton, children were held separately from adults. Nationally, children could still be sent to adult prisons until 1899.

‘Children of the perishing and dangerous classes’ – Reformatory Schools

North Riding conviction records of juvenile offenders, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, frequently list their sentences as a short period at Northallerton prison with hard labour, followed by 4-5 years at a Reformatory School.

Before this period, no distinction was made between how adult and juvenile offenders were tried and sentenced. The early-nineteenth century saw an increase in recorded juvenile crime, leading some, especially Christian reformers, to worry about the spiritual health of the next generation.

The 1854 Youthful Offenders Act allowed courts to sentence children under 16 to a stint in a reformatory for between two and five years as an alternative to prison. However, they generally served an initial sentence of at least 14 days in an adult prison.

Conviction records from the North Riding Quarter Sessions rarely specify which reformatory a juvenile offender was to be sent to after completing their prison sentence. One that does occasionally pop up on our records is the Castle Howard Boys’ Reformatory School, in Welburn, near Malton. In the 1881 census, there are 73 boys living at this Reformatory, between the ages of 10 and 19. Some have been sent from as far afield as Manchester, but most are from the Yorkshire area.

Punishment or rehabilitation?

Mary Carpenter (1807-1877), a philanthropist and social reformer, was instrumental in the establishment of reformatory schools across the country. In 1851, she published Reformatory Schools for the Children of the Perishing and Dangerous Classes and for Juvenile Offenders, advocating for the necessity of a different approach to the punishment of child convicts. This alternative was intended to negate the injuries inflicted on a child by the Gaol, and reform, rather than simply deter children from reoffending.

Her idea of the Reformatory sounds somewhat idyllic: somewhere where “love must be the ruling sentiment,” and “no punishments of a degrading or revengeful nature will ever be employed.” Little archival material has been left behind by most reformatories, much less relating to the inmate’s experience. For some children, it did have the desired effect – for example, juvenile offenders like Sophia Constable never reappear in our conviction records.

In other cases, inmates of reformatories are reconvicted for assault, declared beyond the reach of reformatory treatment, or even enact riotous outbreaks, as at West Riding Reformatory for Girls’ in Doncaster, in July 1876. Reported in newspapers countrywide, the “mutiny” began with three girls’ disobedience, which sparked a revolt of more than a hundred girls. Several windows were smashed and police struggled to subdue the girls for some time and regain control. Four girls seen as the ringleaders were sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour the following week. (Sophia Constable also may still have been an inmate at the West Riding Reformatory at the time of this event)

Further still, many of the records we hold that mention the Castle Howard Boys’ Reformatory School, are reconviction records for its inmates. One example: George Arnold and Samuel Hill alias Cox. Both had multiple previous convictions and had caused disturbances at Reformatory Schools before Ishmael Fish, superintendent of Castle Howard Boys’ Reformatory School, declared them beyond the reach of reformatory treatment.

Notes on the previous convictions and misbehaviour of George Arnold and Samuel Hill alias Cox, inmates at the Castle Howard Reformatory – both are considered quite beyond the reach of reformatory treatment (left) & covering letter from Ishmael Fish at Castle Howard Reformatory School to Captain Gardner, 27 June 1864 (right) [QSB 1864 3/9/9]

Other juvenile offenders

John George Kershaw

Photograph of John George Kershaw, age 11, in the Police charge book, 7 August 1875 [QP]

John George Kershaw was born in 1864 in Tow Law, County Durham.

During the Michaelmas Quarter Sessions of 1875, John is convicted, aged only 11, for stealing a horse from farmer John Porritt at the township of Brotton. On 30 August 1875, whilst employed by Porritt to help with the harvest, Kershaw disappeared, having stolen one black cart horse, one pad and one bridle and conveying them to Stockton in County Durham.

Kershaw was apprehended the next day in a field near ‘Elton gate’ by Robert Harrison, Inspector of Police in the County of Durham, and the horse was found and identified by Kershaw in a field at Burnholm Farm (Elton, Stockton) – roughly 23 miles from Brotton. After being received into custody by James Cooke, Police Constable at Guisborough, Kershaw said he had put the saddle and bridle on the horse to take it to a “Mr Yeoman’s” at Stockton.

John George was convicted on 6 September 1875 and sentenced to one calendar month at Northallerton Gaol with hard labour, then five years in a Reformatory. Which reformatory John George was sent to has not been identified.

The next time John appears in the records is the 1881 census when he is 16, back in Brotton living with his mother and father. John’s profession is listed as Blacksmith.

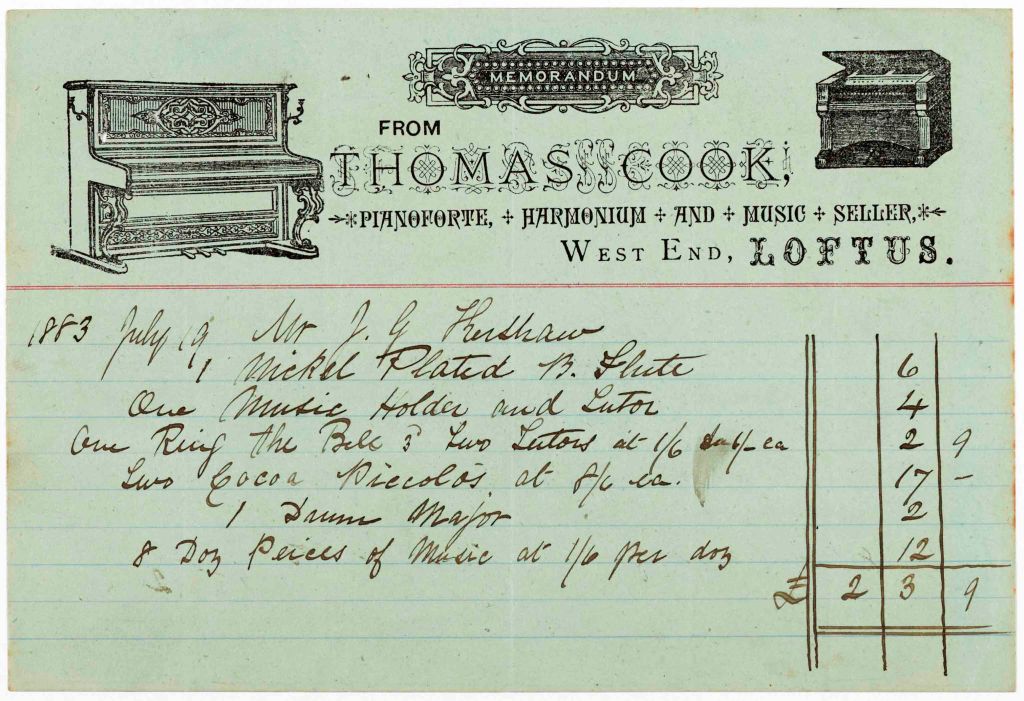

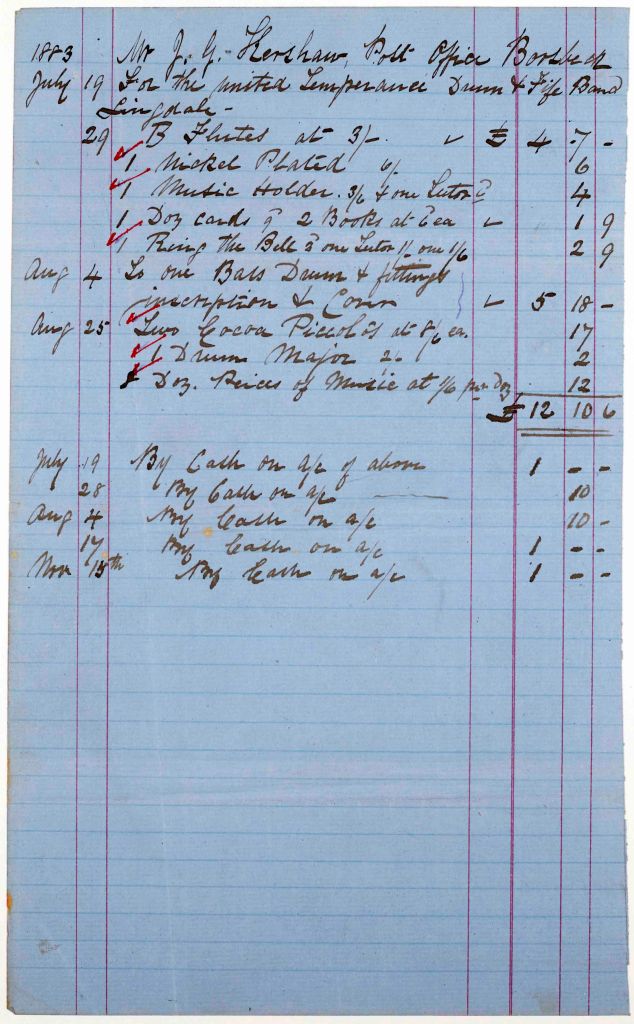

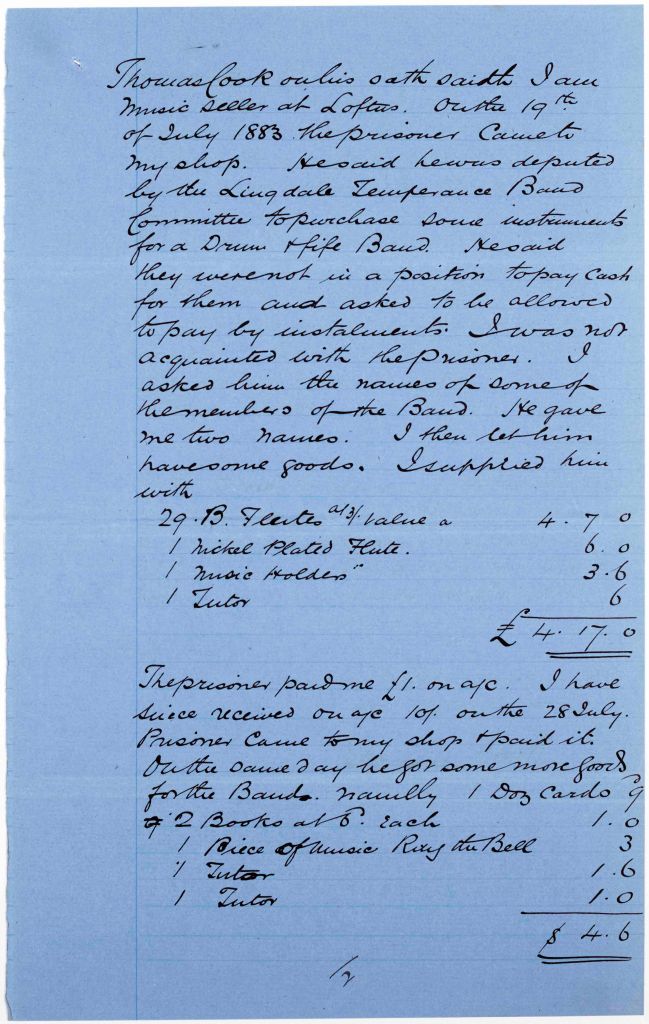

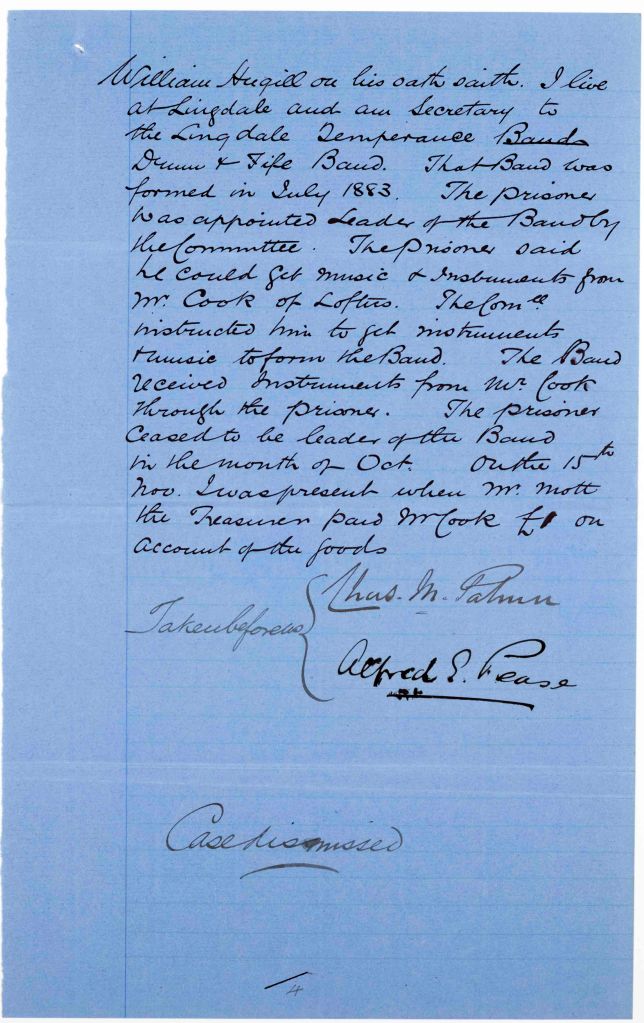

In December 1883, John joins the Yorkshire Regiment (notably stating he has no prior convictions). The same month, John reappears in the North Riding Quarter Sessions records – this time accused by Thomas Cook, music seller of Loftus, of stealing a flute, a music holder, two cocoa piccolos and a quantity of music. However, the case was dismissed, and a receipt for the goods, purchased by John on behalf of the United Temperance Drum and Fife Band of Lingdale, was produced.

Bill of Thomas Cook, pianoforte, harmonium and music seller at West End, Loftus for goods supplied to J.G. Kershaw on 19 July 1883 [QSB 1884 1/8/11]

Bill for musical goods supplied to John Kershaw at the Post Office at Boosbeck for the United Temperance Drum and Fife Band at Lingdale in July and August 1883, with payments made on account between July and November 1883 [QSB 1884 1/8/11]

Cover sheet, annotated ‘Dismissed case’ and 4 pages of depositions of Thomas Cook of Loftus, music seller, and William Hugill of Lingdale, witnesses in the case against John George Kershaw for obtaining a nickel plated flute, a music holder, two cocoa piccolos, and a quantity of music from Cook by false pretences, dated 14 December 1883 [QSB 1884 1/8/11]

In the 1891 census, John still lives with his father, and appears to be working as a Stationary Engine Man. In September 1891, John George marries Rebecca Faulkner. In September 1892, they have a son, Joseph Faulkner Kershaw who is baptised at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Castleford, West Yorkshire. By the 1901 census, John is living in Skelton with wife Rebecca and son Joseph.

John died in September 1906, aged only 42, in Lingdale. He is buried in Brotton cemetery.

Isabella Scales

Isabella Scales was born in 1857. She was baptised in 1857 in Pickering; her mother is listed as Elizabeth Scales, singlewoman. In the 1861 census, she is living in Pickering with her mother and her grandfather.

Photograph of Isabella Scales, age 15, in the Police charge book, 21 December 1870 [QP]

At the Christmas Quarter Sessions in January 1869, Isabella was first convicted at age 11 for causing grievous bodily harm by poisoning the family of John and Elizabeth Dodsworth, where she was servant. Information from the depositions of witnesses at her trial give a very detailed account of the crime.

On 13 December 1868, John Dodsworth was presented with a yellow pot of poison by a Mr Bruce, intended to be given daily to an unwell horse. He put it on a high ledge and instructed his wife and Isabella that it was poison and was to be kept from the children. On 21 December, Elizabeth, Isabella and the three children had coffee sweetened with sugar at breakfast – but, Elizabeth noted, Isabella abstained from taking sugar in her coffee, saying that she preferred treacle, although she had taken sugar previously. Elizabeth and the three children fell ill soon after.

John and two servant boys, William Barnes and John Myers, returned from work at 3 o’clock for a dinner of pig’s head, cold mutton and coffee. Elizabeth also had more coffee. All were sick (apart from Isabella) and a doctor was called at 11 o’clock when Elizabeth was still vomiting. The next day, Elizabeth brewed some camomile tea for the three children and Isabella, again sweetened with the sugar. This time Isabella drank the tea and was sick. Later, when Elizabeth tasted the sugar before adding it to the tea, it tasted “like alum.” She threw the contents of the sugar basin into the fire.

When Elizabeth accused Isabella of poisoning the sugar, Isabella first blamed the three-year-old son Tom, although claiming she had helped him to reach the yellow pot from its ledge. The same day, Isabella was charged with poisoning the sugar. The prisoner admitted to the crime. When asked how she did it, she replied “I took it into two fingers and mixed it up.” Upon being asked her reasoning for doing so, she said she had done it to poison the two boys (Barnes and Myers, presumably), stating:

“I shouldn’t have done it but the boys […] pushed me about.”

All recovered from their sickness, but Elizabeth was ill for several days, complaining to the surgeon of “heat in the stomach, pain in the bowels, nausea, thirst and great debility” [QSB 1869 1/8/27].

Isabella was sentenced to just one day’s imprisonment at the gaol.

Two years later, she was convicted again for obtaining under false pretences various goods from a shop belonging to Nawton Maw in the township of Rosedale East Side. She had claimed that the ten yards of cobourg, three yards of holland, a pair of boots, buttons, six yards of calico and a piece of velvet (with a total value of £1 6s 6d) were for a Mr Swainbank. The offence was committed on 27 August 1870, but she was not brought into custody until 19 December, when Christopher Swainbank and his wife Jane received the bill [QSB 1871 1/8/14].

A letter from John Watson of Pickering to T.T. Trevor, Clerk of the Peace, dated 27 December 1870, referring to her past conviction and present trial, states:

“The prisoner Isabella Scales you will I dare say remember was two years ago tried and convicted at Northallerton for poisoning a family […] She is really a bad girl and I am afraid will have to pass (unless she reforms) the greater part of her life in confinement” [QSB 1871 1/9/2, see below].

Letter from John Watson of Pickering to T.T. Trevor, Clerk of the Peace, dated 27 December 1870, referring to Isabella Scales’ past conviction and present trial [QSB 1871 1/9/2]

This time, she was sentenced to imprisonment for fourteen days at Northallerton followed by three years at a reformatory. Isabella has been traced to the Sunderland Reformatory School for Girls at Bishopwearmouth via the 1871 census.

No later trace of Isabella has, so far, been found within census, parish, or North Riding Quarter Sessions’ records.

Sources and further reading:

Other blog posts on the North Riding Quarter Sessions:

- Introducing the Quarter Sessions and those who attended: All Human Life: North Riding Quarter Sessions, 1660-1971

- The various types and subjects of the Records of the North Riding Quarter Sessions

- The Working papers of the North Riding Quarter Sessions

- Previous blogs on stories of criminal women who appear in North Riding Quarter Sessions’ records

- North Yorkshire Quarter Sessions’ scandals

Parish registers and local newspapers:

- Ancestry UK: UK Parish Baptism, Marriage and Burial Records search webpage

- Ancestry UK: UK Census records search webpage

- Find My Past: Yorkshire parish registers list webpage

- The British Newspaper Archive website

Free access to the Ancestry UK, Find My Past, and British Newspaper Archive subscription websites is available via computers in most North Yorkshire libraries as well as our Archives’ searchroom, by appointment.

Carpenter, Mary, 1851 Reformatory Schools for the Children of the Perishing and Dangerous Classes and for Juvenile Offenders

For more information on, and lists of, Reformatory schools and the whereabouts of their records, see the Children’s Homes webpage on Reformatory Schools

*Further records for Castle Howard Boys’ Reformatory are held at East Riding Archives, and those for West Riding Girls’ Reformatory are held at City of Doncaster Archives (annual reports for 1868-1869 only).

I always find the newsletter articles from North Yorkshire Archives fascinating, so thank you.

I was particularly interested in this one as my great aunt, in 1881, appears in the census of The Aismunderby cum Bondgate Indudtrial Home (Ripon). She was 10 years old. I have tried to delve further into this splendidly named establishment without success so I have very little idea why she was there, what the purpose of the place was and whether it was voluntary or not. Her mother had died the previous year so maybe the Industrial Home was some kind of orphanage? Have you any details of it in your archive?

Thank you for your time

Sally Neish

Hi Sally,

Thanks for getting in touch. We’re pleased that you enjoy the blog.

We think that the home may have been more commonly referred to as the Ripon Industrial Home for Girls, some information relating to it can be found here: https://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/RiponIH/. Unfortunately, we do not appear to hold any records from this home so we can’t help further on this occasion.

Thanks – North Yorkshire Archives