by Mia Cox, Archivist

Parish registers were introduced in 1538, when Thomas Cromwell ordered that each parish of the Church of England keep registers of all baptisms, marriages, and burials. Cromwell’s injunction was met with strong resistance. A penalty of 3s 4d was imposed (£73.55 today according to the National Archives Currency Converter 2017), going to the repair of the Church for failure to fill out the register. Cromwell’s instruction was reissued in 1547, and again in 1559, the penalty now divided between the repair of the Church and for the benefit of the poor.

In 1597 the Convocation of Canterbury ordered the registers to be written on parchment or vellum, to stop deterioration, and that the older registers be transcribed. Bishop transcripts were also introduced to prevent fraudulent entries and ensure the registers were being maintained.

During the English Civil War (1642-1651), parish records were poorly kept, and many went missing. For a brief period in 1651, Parliament confusingly appointed the position of ‘The Parish Register’, who oversaw civil records of births, marriages, and deaths. Marriages cost 12d (£5.18) to record, births and burials cost 4d (£1.73) and baptisms were free. In 1660 (the restoration), parish registers were restored and returned to the clergy.

An Act of Parliament was passed in 1694 during the reign of William III to raise money to fund the war against France. Marriages increased to 2s 6d (£14.98), burials to 4s (£23.97) and births to 2s (£11.98). Nobility was subject to higher costs – a Duke’s marriage being £50 (£5,991.70) to enter in the Parish register and the birth of his first son cost £30 (£3,595.02).

These taxes were further enforced in 1696, when parents were ordered to register the birth of every child for 6d (£3), with a fine of 40s (£239.67) for failure to register within 5 days of the birth. The clergy were also fined if they failed to keep records of those born and not baptised. This left some clergy liable to an increase in fines and in 1705 an act of indemnity was passed to aid those who had neglected to fill out the registers.

Early examples of a parish register: Topcliffe baptisms, 1577 (left) and Topcliffe burials, 1607 (right) [PR/TOP 1/1]

Early registers of baptisms, marriages and burials were recorded together in the same book in chronological order, normally in Latin. Baptisms and burials also had to be written in within seven days of the event.

To begin with there were no rules for the wording of entries, it was up to the clergyman to decide what to record. In 1733 the use of Latin was abolished, though many had stopped using Latin prior to this date. In this Wensley register you can see where Latin was used up until 1725 and English was picked up at the top of the right page. In addition, the Marriage Act of 1753 aided a more systematic recording of marriage entries.

Wensley register, 1724-1725 showing when the use of Latin stops, and English begins [PR/WEN 1/1]

Under the Stamp Duties Act of 1783, a cost of 3d (£1.08) was imposed on each entry to raise money to pay for the American War of Independence. Paupers were exempt and marked as such on the register. The tax was largely unpopular and was repealed in 1794. You may find your ancestor avoided paying the tax and got baptised later in life, after the Act was abolished!

In 1777, Dade registers were introduced throughout Yorkshire. Developed by William Dade, a Yorkshire clergyman, Dade registers contain significantly more information than previous registers. Dade wrote in 1770 – “This scheme if properly put in execution will afford much clearer intelligence to the researches of posterity…”

However, many resented the extra work needed for the Dade registers and refused to follow the new rules – thus when the archbishop indicated there would be no punishment for failure to comply, the registers were eventually superseded by Rose’s Act, introduced in 1812.

Scruton Dade Register, 1798-1799 [PR/SCR 1/4]

George Rose’s Act of 1813 meant separate registers were introduced for baptisms, marriages, and burials.

Rose thought it was “highly desirable [that parish registers] should be regularly entered and safely deposited.” The Act meant more information was recorded than previous registers, but less than suggested by Dade. Each parish was supplied with printed books with uniform sections to record information. The clergy therefore only needed to fill each entry with the correct information, and whilst some followed these rules exactly, others preferred to make good use of the extra space and large margins…

John Hayton, Curate of Arkengarthdale, writes alongside the required name, abode, date and age that Mary Colling was “killed by lightning – verdict: departed this life by the visitation of God” – a visitation from God meant the death was likely to have been sudden or for a reason they did not have a medical explanation for at the time.

Arkengarthdale burial register, 1833 [PR/ARK 1/6]

R.F. Dent, Vicar of Coverham, provides context to the death of a young boy in 1868 – “this boy and his horse were killed by lightening when on the road from Middleham High Moor on Saturday June 20, 1868.”

Coverham burial register, 1868 [PR/COV 1/7]

Ralph Prowde, Vicar of Kilburn, writes alongside the death entry, a short description of Job Skelton:

“eccentric and well-known character (son of eccentric mother) – remarkable for profuse growth of his hair worn in plaits. Found dead in bed – inquest. Died by himself – since wife’s death in 1875. On charity and sale of his photograph.”

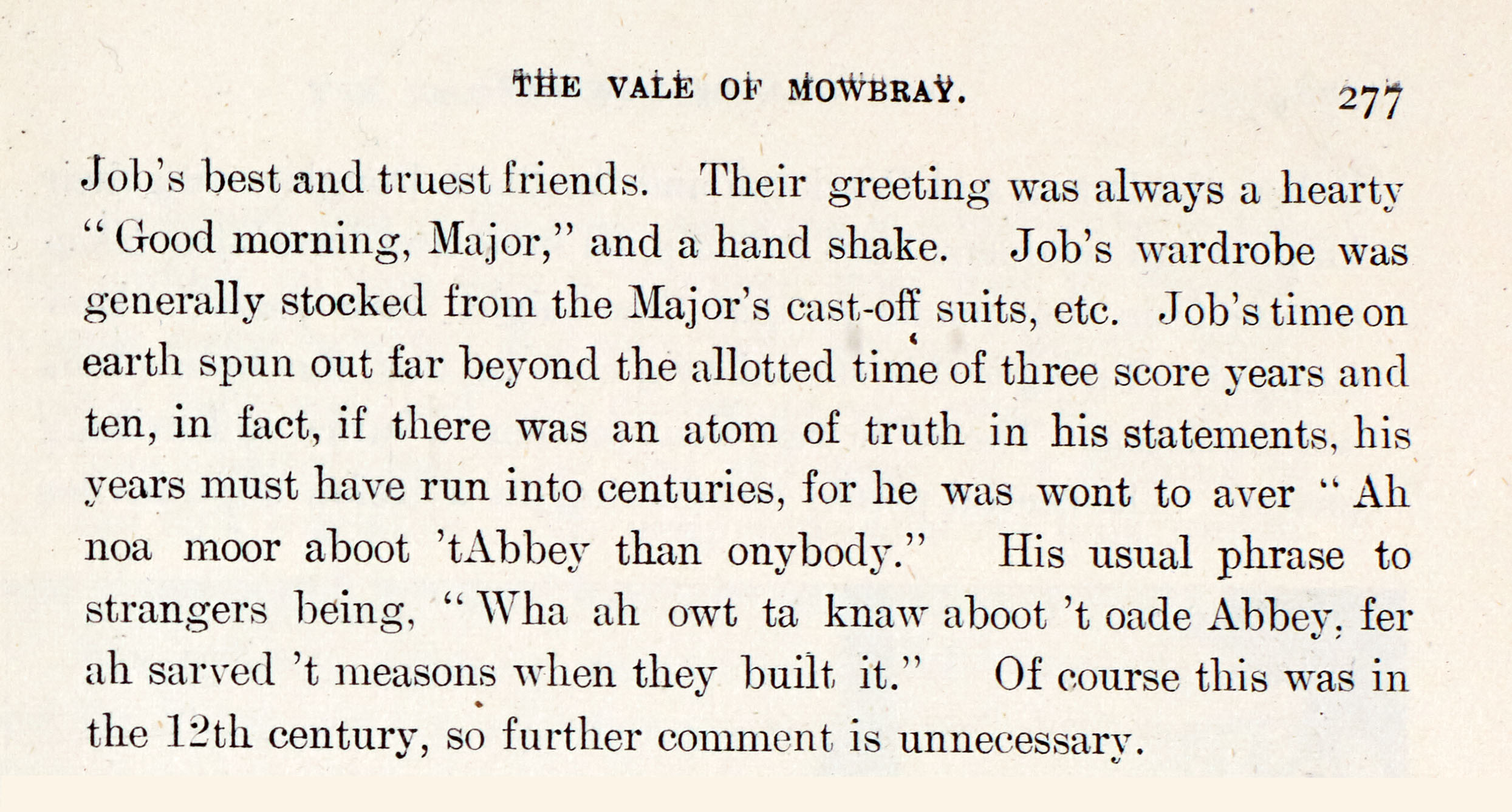

Job Skelton of Byland and Wass died 16 April 1881 aged 80. Job was well known in the community, and was photographed by J.R. Clarke, Thirsk based photographer, and written about in Edmund Bogg’s text on Richmondshire and the Vale of Mowbray (1906).

Kilburn burial register, 1880 [PR/KLB 1/10] and Job Skelton in Bogg’s text

The addition of comments such as these provide wonderful context to people and their lives – despite the clergy not being required to provide any further information than the necessary headings. Here are some other interesting examples of notes in the parish registers.

South Otterington burial register, 1891 [PR/OTS 1/8]

“Found killed by a train. Native of Grimsby. Not heard of by his relations for 8 years. A sailor.”

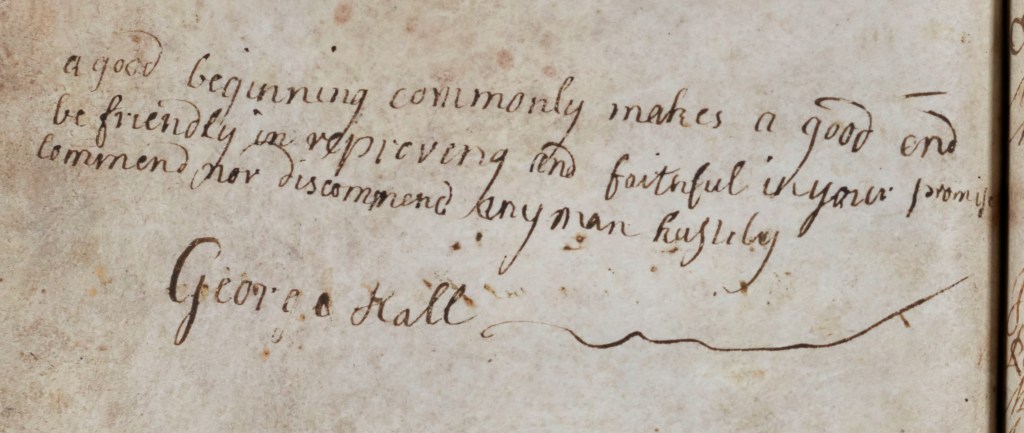

Great Smeaton register, 1573-1667 [PR/SMG 1/1]

“A good beginning commonly makes a good end, be friendly in reproving and faithful in your promise, commend nor discommend any man highly.” Note by Reverend George Hall.

Askrigg burial register, 1841 [PR/ASG 1/7]

“No 794 to 801 inclusively died of smallpox – all being unvaccinated except 799 and she very sickly. Upwards of 80 cases of smallpox in Askrigg and only one death after vaccination.”

Helpful context to family history research on smallpox deaths in Askrigg.

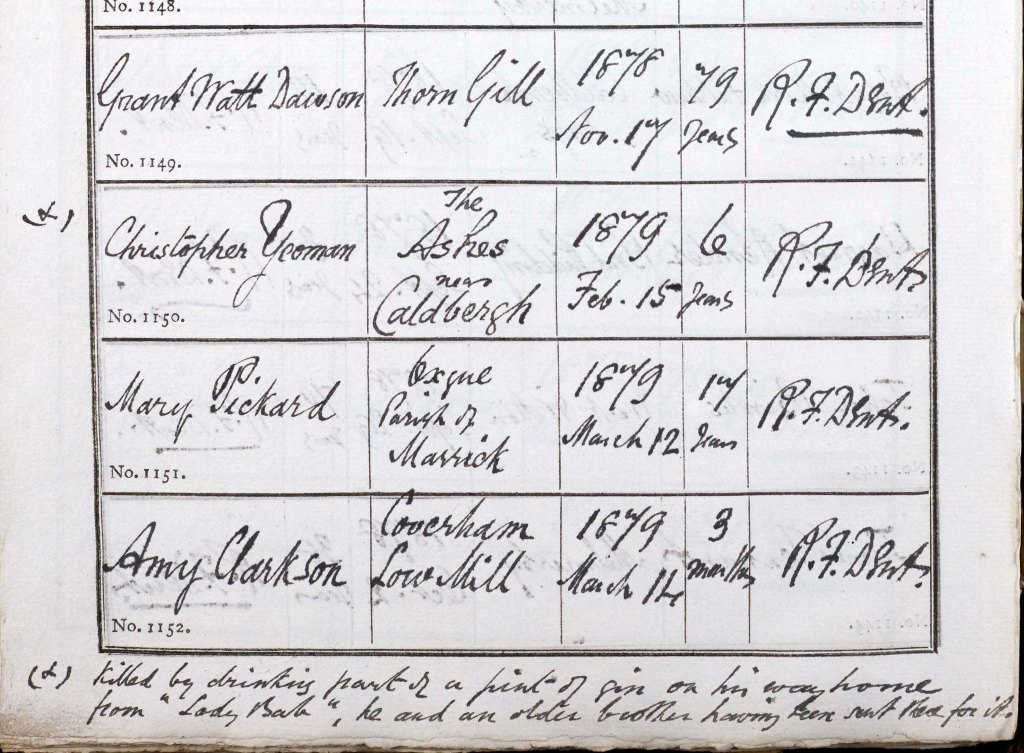

Coverham burial register, 1879 [PR/COV 1/7]

“Killed by drinking part of a pint of gin on his way home from Lady Bab, he and an older brother having been sent there for it.”

Despite the success of Rose’s Act, with registers having remained largely unchanged since their separation, the initial Act was badly drafted and written. For example, if a clergyman was found to have been negligent with his entries, falsifying them, or found to have destroyed or damaged a register, the informant was to receive half of the fine paid. However, the Act neglected to provide any fine, with the only penalty being 14 years transportation! Thus, committing the informant of a rogue clergyman to seven years transportation…

Parish registers remained with the introduction of civil registration in 1836, but Bishops’ Transcripts ceased. Under the Parochial Register and Records Act of 1978 the clergy were encouraged to transfer parish registers to the relevant county record office for safe storage – ensuring they end up in the safe hands of your local record office!