by Jo Faulkner, Record Assistant

This blog coincides with our latest exhibition, showcasing a selection of records from our archive collections relating to the drinking of alcohol and the rise of the temperance movement.

- Introduction

- Brewing

- The Pub

- Drinking at Home

- The Rise of Temperance

- The Road to Ruin

- Taking the Pledge

- Temperance hotels

- Meets and events

Introduction

The Victorians and Edwardians were particularly concerned about drinking and drunkenness. Industrial-scale brewing, huge growth in the retail trade and venues which sold alcohol resulted in more choice and availability for the drinker during this period.

Scrutiny focused on the working classes. It was widely accepted that working men would frequent the many public houses that existed in most areas, particularly in the booming industrial towns and cities. For upper class men, drinking in their exclusive clubs denoted a certain cultural status. Studies concluded that drinking alcohol was associated with ideas of masculinity, which linked with a wider argument in support of drinking – liberty and freedom of choice.

Women of any class who drank were frowned upon by Victorian and Edwardian moralisers, but women continued to drink. Making and selling home-brewed alcohol was part of everyday domestic life for many. Women, like men, drank to socialise and relax. Upper-class women also drank alcohol, though it was only when dining and entertaining that it was thought socially acceptable. Women of the lowest status often drank publicly, drowning away sorrows or sometimes perhaps in defiance of social expectation.

Alcohol has at times been prescribed for medical reasons. The benefits of stout for pregnant women and new mothers persisted for generations. Drinking for medicinal reasons made alcohol acceptable during times when the temperance movement posed a threat, and some producers of alcoholic drinks rebranded them as tonics.

People had many different reasons for drinking, but the inescapable fact is that often the purpose was simply enjoyment of intoxication. History has shown that however attempts have been made to stigmatise, limit, or prohibit drinking alcohol, people continue to drink.

Drinkers at the Ship Inn, Frenchgate, Richmond

Temperance was unpopular with the many people in society who’s living depended on the production and consumption of alcohol and those who considered it as an infringement of their freedom to choose. They included:

Business owners – Brewing played an important part of the economy of both rural villages, market towns and later cities. Clearly those who made their living from breweries were impacted by the growing temperance movement in the nineteenth century. The knock-on effect could mean that not only brewers but their employees, carters, coopers, publicans and their staff would suffer the consequences of any reduction in alcohol consumption.

The working man – The culture of drinking had become embedded as means of relaxation for working men (and some women), who had little time to socialise and few other freedoms. In the conflict between his Methodism, which had emerged as the religion for the working man and the abstinence which it began to preach, some men would decide that an insistence on teetotalism was a step too far.

Political parties – The Conservative party traditionally opposed the temperance movement and largely supported the interests of the alcohol industry and associated economy.

Brewing

Alcohol has been a solid commodity throughout modern history. From the smallest of home breweries to the mass production achieved by the twentieth century, it has played an important part in the economy of communities and the nation. Commercial brewing in the community originated at taverns and alehouses. The number of common brewers, who did not own pubs themselves, grew rapidly in the 18th century. Licensing was controlled by Magistrates.

Masham Lightfoot Brewery staff [EF 361/134]

Masham is perhaps best known for the brewery founded by Robert Theakston, who began brewing in 1827. Parts of the site owned by Theakstons were once the Lightfoot Brewery, which was bought out by Theakstons in 1919. The photograph appears to have been taken shortly before the sale. The Lightfoot and Theakston families were linked through marriage. It was rumoured that Theakston took over Lightfoot because they had a better cricket team.

This photograph of a brewery wagon was taken at Spacey Houses, Pannal. The area of ‘Spacey Houses’ is named after the Spacey family, who owned a farm on the site in the 18th century. The Leeds-Harrogate turnpike road ran through the area and inns along the road served travellers. Like many inns and public houses, the Spacey House Inn had its own brewery attached.

Brewery wagon at Spacey Houses, Leeds Road, Pannal [OR00046]

The Nesfield Brewery, Scarborough, pictured here in 1961, was founded in 1691 by the Nesfield family. It was acquired by Moor and Robson’s Breweries in 1919. Brewing at the site continued until 1932. Parts of the building remain.

Nesfield Brewery, Scarborough, 1961 [SC104510]

The Pub

The history of pubs can be traced back to Roman ‘tabarnae’ (taverns) and Anglo-Saxon alehouses which are likely to have grown from domestic brewing and became a focal point for social gathering and exchange of news.

Pubs as we recognise them today began to appear in the early 1800s. There was huge growth in public houses after the Beer Act of 1830 loosened regulations relating to the manufacture and sale of beer. The industrial revolution saw enormous growth in numbers of public houses. Breweries sought to secure markets by buying up pubs. At this time lavish fittings such as tiles, engraved glass and brass taps created an environment which would have seemed bright and lavish compared to the living accommodation of many customers.

The Farmers’ Arms Inn, Scruton [ZZF 3/10/18]

The Farmer’s Arms at Scruton was, in 1891, home to John Fothergill, his wife Mary Jane and their seven children.

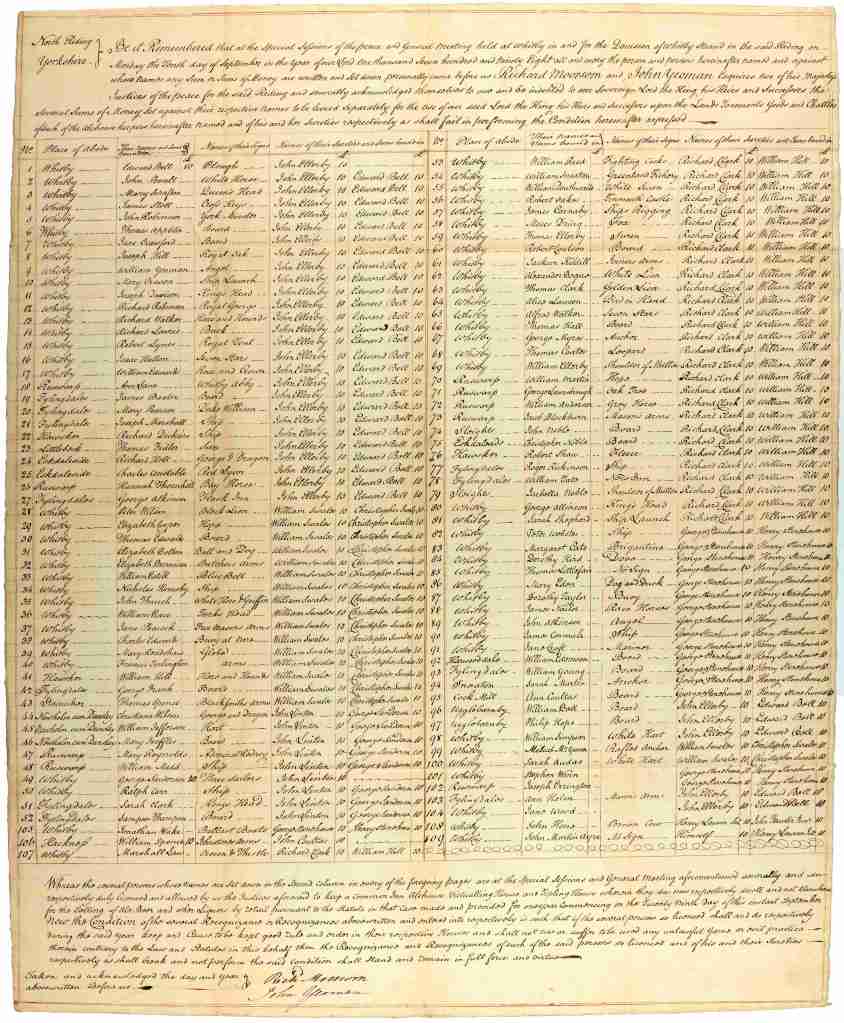

Records relating to victuallers and alehouse keepers held by the North Yorkshire County Record Office include returns of alehouse keepers’ recognizances. These bonds were for the maintenance of good order, taken usually before two Justices in special ‘Brewster’ Sessions and returned to the Clerk of the Peace. An Act of 1551 required victuallers’ recognizances or bonds for good behaviour. The Alehouse Act of 1828 abolished the system of recognizances and sureties.

Return of alehouse keepers’ recognizances Whitby Strand [QSB 1798/4/12]

Drinking at Home

Domestic brewing began as a necessary everyday activity for producing a staple drink, carried out in cottages and kitchens from the medieval period. By the 16th century the dedicated brewhouse had become widespread. In the medieval era, brewing on a larger scale was carried out in monasteries. By the 18th century large country houses often had their own purpose-built brewhouses.

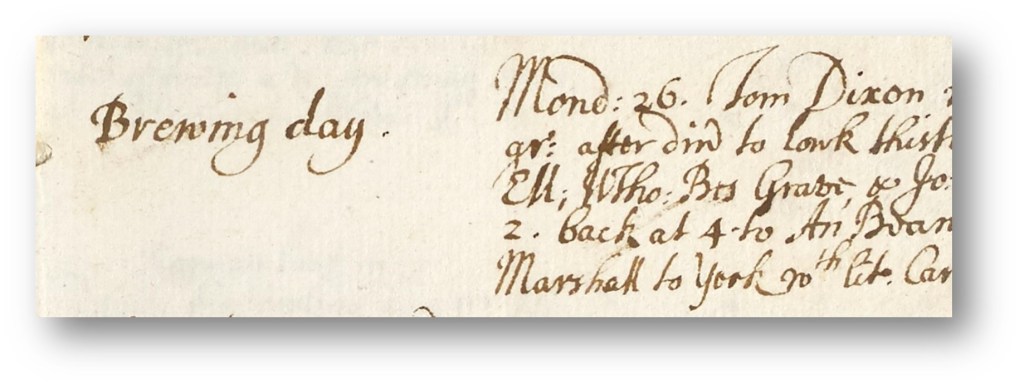

This diary entry from the Cholmley/Strickland of Whitby archive, records that 26th June 1671 was brewing day [ZCG V/8/5]

In many households, making wine had always been an essential way of preserving produce. A good housekeeper was admired for frugality and the ability to create tasty food and drink from all kinds of available ingredients.

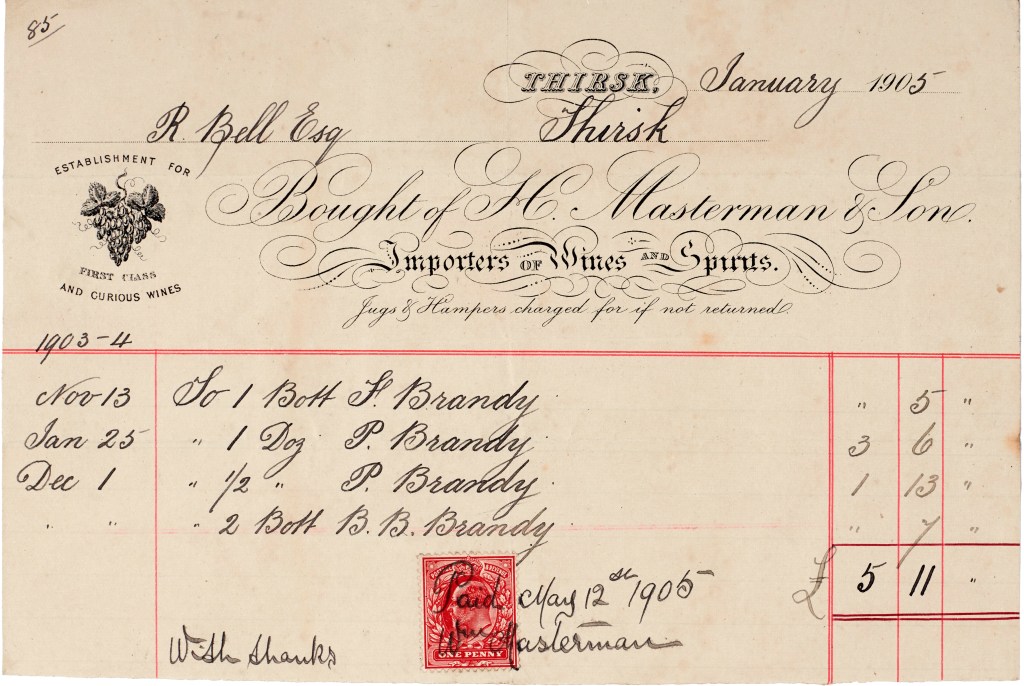

Those with sufficient wealth could buy, imported wines and spirits from merchants. Consuming the ‘right sort’ of drinks and observing appropriate etiquettes around drinking, promoted social status. High import duties caused wine to remain a luxury until the 1860s. The butler, a senior confidential servant, was responsible for managing the cellar. Cellar books were kept to record when wine was purchased for and removed from the cellar.

Receipt for brandy purchased by Reginald Bell of Thirsk Hall, January 1905 [ZAG/A/3/14/8448]

The Rise of Temperance

In the 17th and early-18th centuries, total abstinence from alcohol was very rare. Those who could afford it enjoyed imported wines and spirits and the working classes generally drank beer and various local brews. The evils of drink and drunkenness, though a nuisance in minor incidents, were not considered to be a large-scale problem. By the mid-1700s, voices advocating the avoidance of alcohol began to emerge. Temperance was always closely connected with religion and particularly the nonconformist churches, which would become a significant influence. In 1743, Methodist founder John Wesley, stated that ‘buying, selling, and drinking of liquor, unless absolutely necessary, were evils to be avoided’. Only a few years later, Hogarth’s famous depiction of the evils of drink in his print of ‘Gin Lane’ prompted a campaign, mainly by the upper classes, to curb the excesses shown.

The earliest temperance organisations started in Scotland and Ireland in the 1820s. The movement spread across the north of England where social problems were already emerging in the growing industrial towns. Soon movements encouraging not just the avoidance of excessive drinking but complete abstinence from alcohol or teetotalism, began to appear.

The strict morality of the Victorian era would result in the development of a range of temperance related organisations and institutions. The first temperance hotel opened in England in 1833. The British Association for the Promotion of Temperance was established in 1835, In 1847 the Band of Hope was founded with the aim to educating children about the evils of drink. In 1876 the British Women’s Temperance Association was formed by women to persuade men to abstain.

Despite support from significant influential groups in society, the temperance movement faded following the Second World War. Prohibition was never imposed nationally in the United Kingdom.

The Road to Ruin

Many of the Quarter Sessions records in the collection held by the Record Office concern offences where drunkenness was a key factor. Drunkenness could lead to nuisance behaviour and frequently violence. It could also increase the likelihood of becoming a victim of crime.

Records also include prosecutions of those enabling drunken behaviour. In 1835, William Bunton, a keelman of Middlesbrough was indicted for ‘keeping an ill-governed and disorderly house, allowing men and women to be drinking, tippling, whoring and misbehaving’.

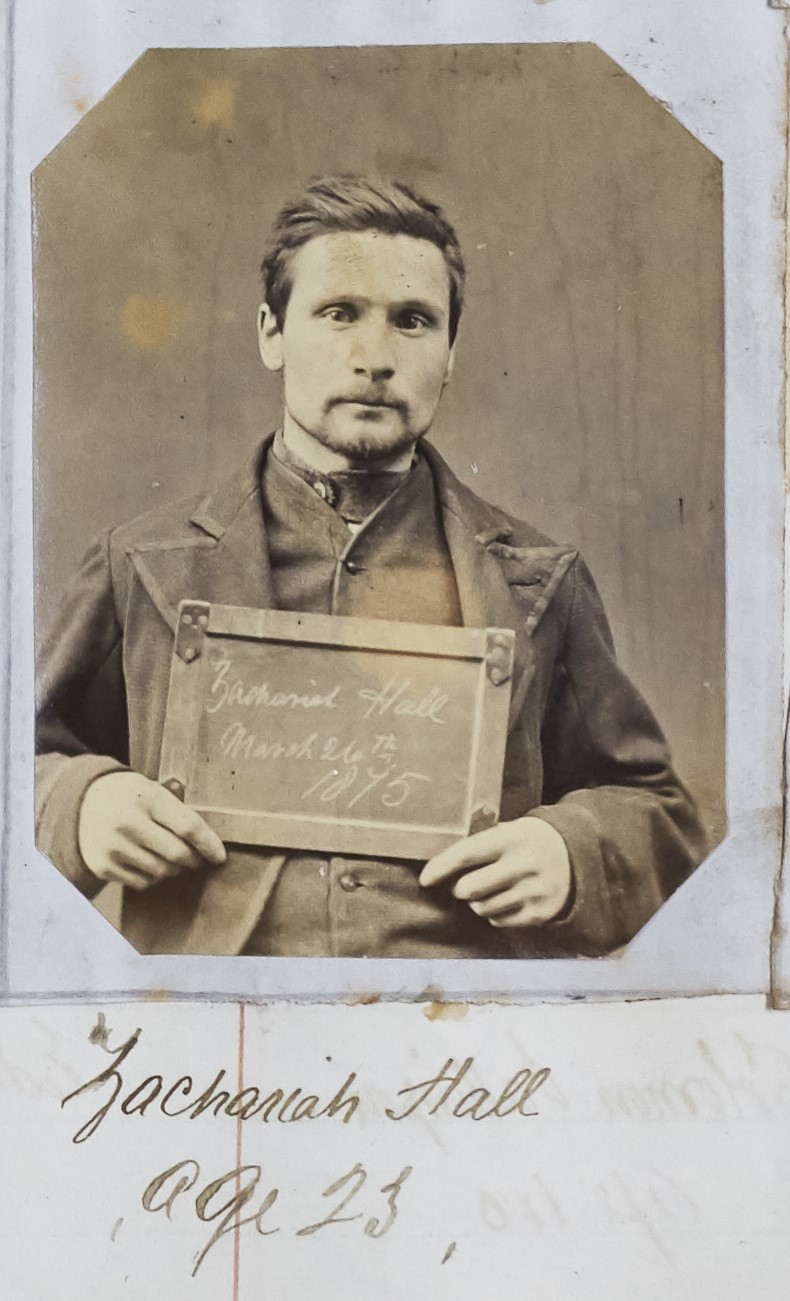

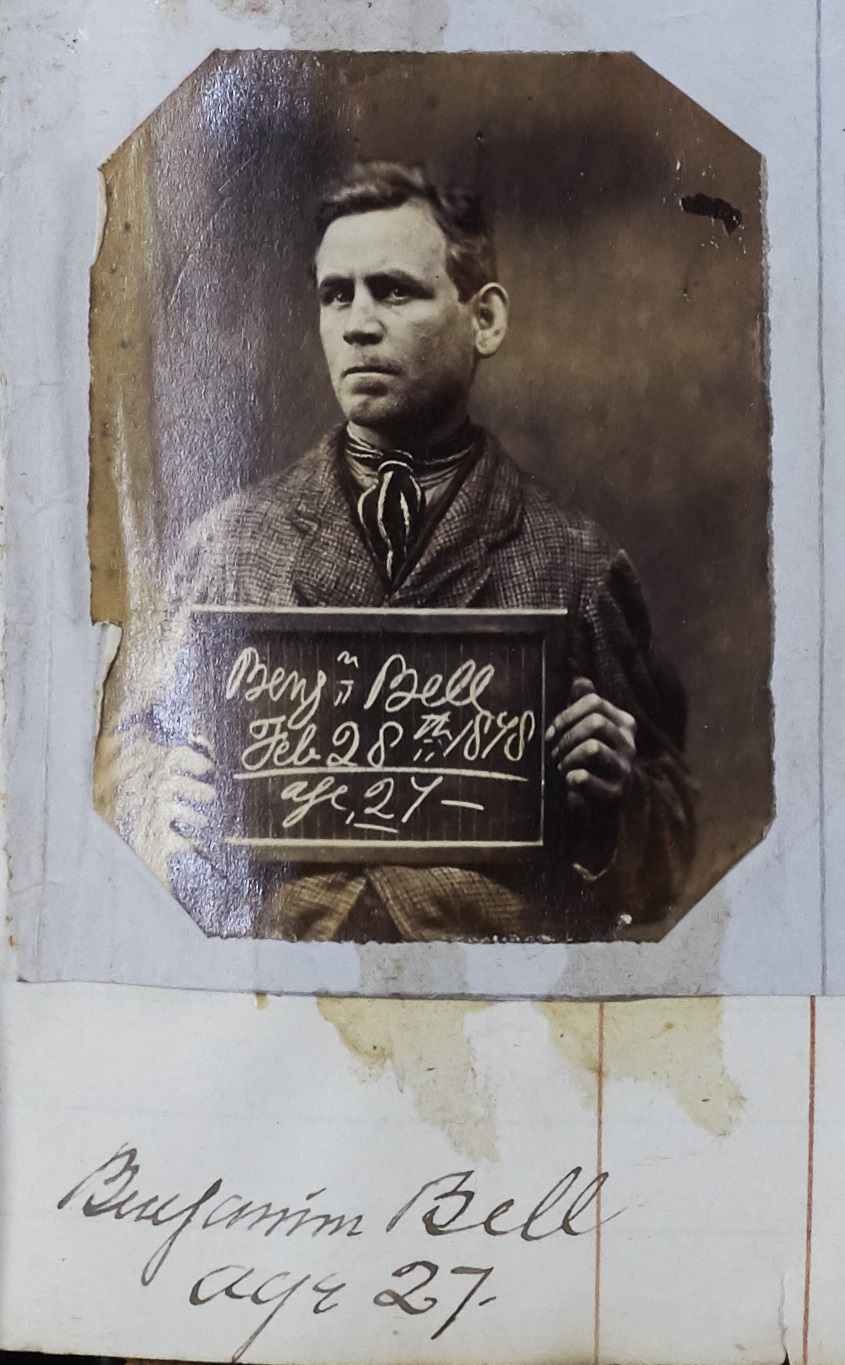

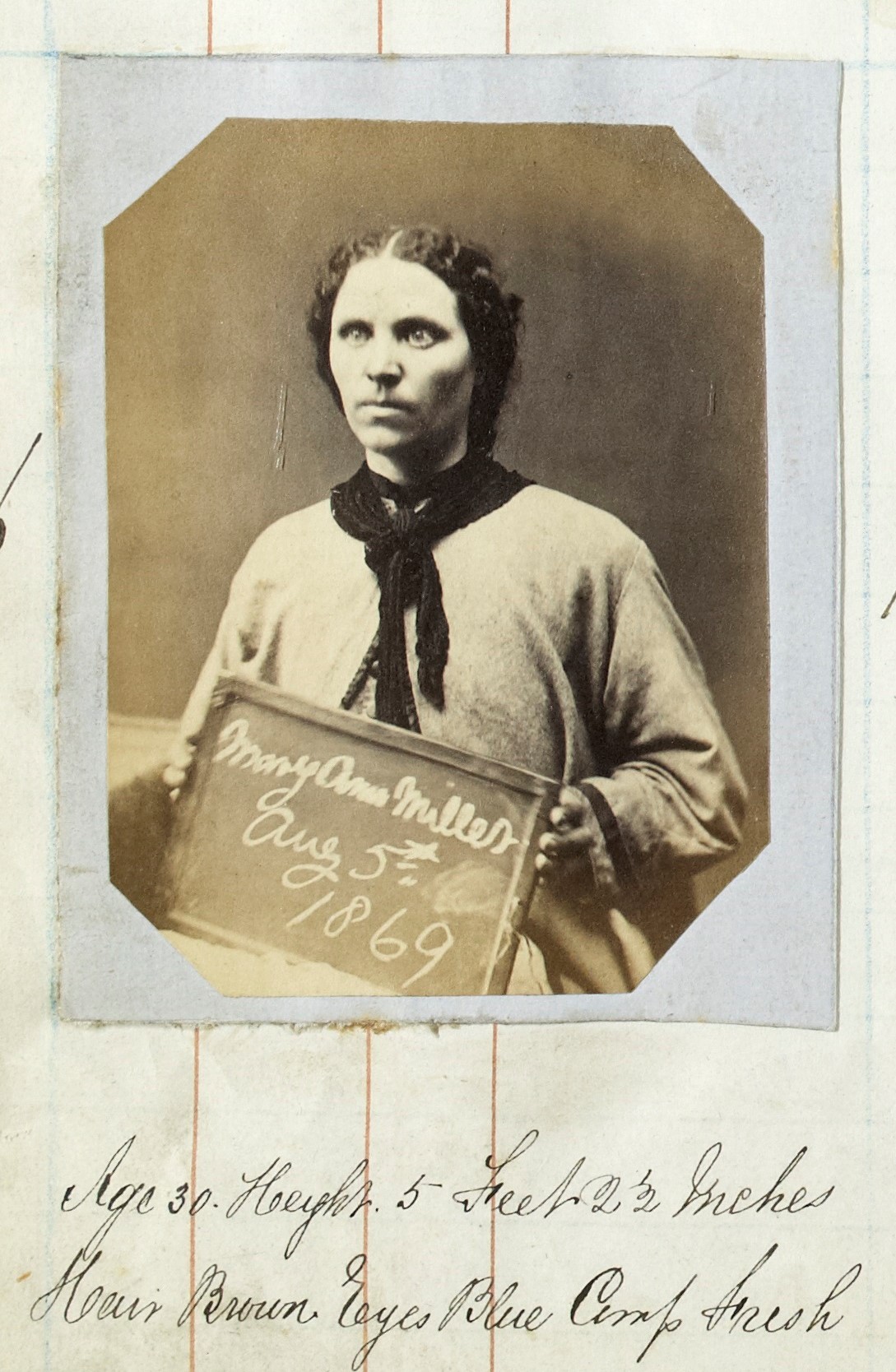

Mugshots of Zachariah Hall, 1875; Benjamin Bell, 1878; and Mary Ann Miller, 1869 from the police charge book [QP]

- Zacariah Hall, a miner from Brotton appeared before the justices on several occasions in the 1870s, charged with being drunk and riotous in the street.

- Benjamin Bell was charged with being quarrelsome and drunk and refusing to leave the premises of Mary Turner of Thirsk. He had various convictions for violent offences.

- Mary Ann Miller was charged with being drunk and indecent in Middlesbrough in 1869 and the following year, under the influence of drink, of stealing clothing from the Crown Hotel at Kirklevington and a leg of mutton in Yarm.

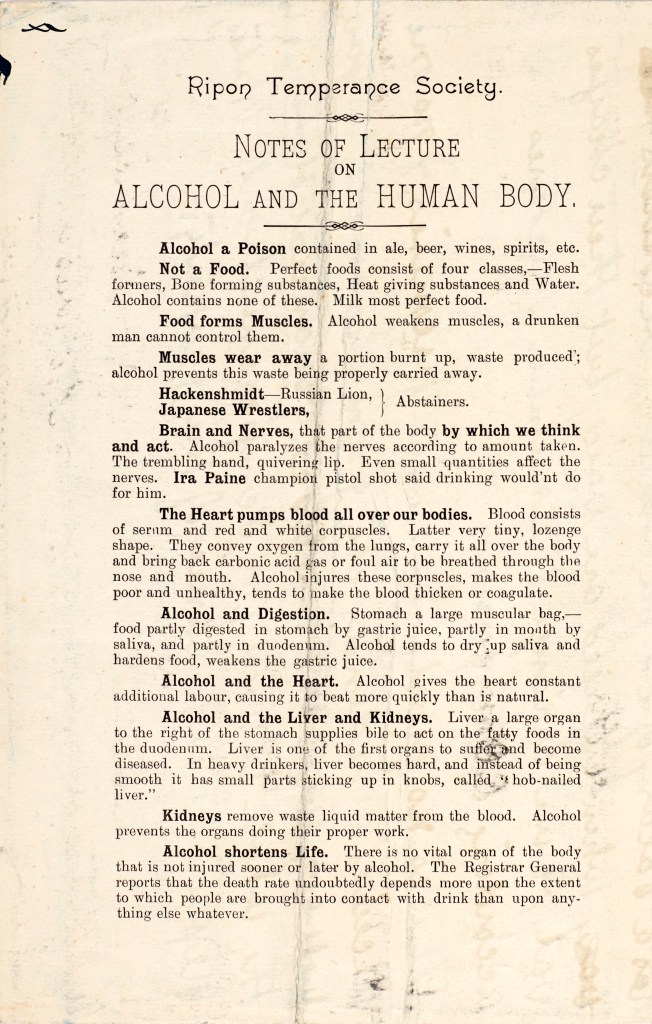

Followers of the temperance movement attempted to persuade drinkers that the habit was not only harmful to their moral wellbeing, but also their health.

Notes on a lecture concerning ‘Alcohol and the Human Body’ printed by the Ripon Temperance Society, described the physical effects of alcohol according to the Society. Modern science and medicine may recognize some of these to be accurate, however we might question some claims such as that it weakens and wears away muscles, paralyzes nerves and hardens food so that it cannot be digested.

Ripon Temperance Society lecture [R/M/RI V/8/1]

Information from records such as Coroner’s inquests show that drinking alcohol was recorded as a cause of death. This abstract of inquests from 1797 records the cause of death of John Fletcher of Snainton as ‘Excess of drinking’.

Coroner’s inquests extract, John Fletcher of Snainton [QSB 1797/4/16/4]

Taking the Pledge

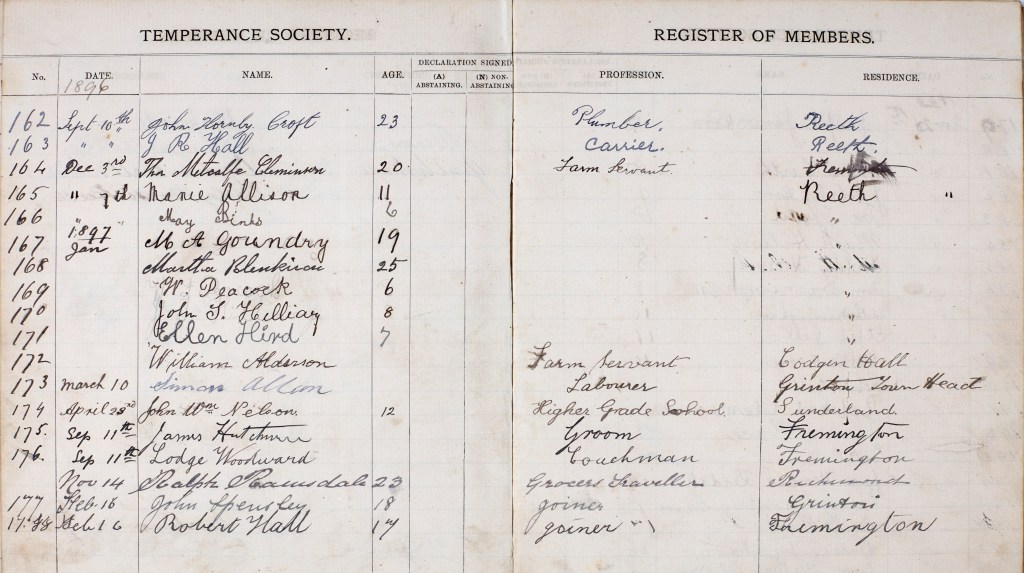

Temperance organisations required new followers to sign a pledge promising not to use intoxicating liquors or provide them to others. They would also usually agree to actively discourage others from drinking and promote temperance. The Record Office holds several Temperance Society registers. This register of members from the Reeth Temperance Society dated 1896, records the names, ages, and occupations of members. Most of the members are working class and are young adults and children.

Register of members of the Reeth Temperance Society, 1896 [R/M/REE 2/8/10]

Besides Methodists, Quakers and Presbyterians, who famously supported temperance, several other influential groups in society supported the movement. They included:

Chocolate manufacturers Quakers such as John Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree promoted chocolate as a temperance drink. Cadbury prohibited the consumption of alcohol in his Bournville village and Rowntree wrote ‘The Temperance Problem and Social Reform’ in 1899.

The Salvation Army A group aligned with Methodism and serving the working-class public, The Salvation Army preached abstinence from alcohol. In response and opposition, a group of publicans funded the ‘Skeleton Army’ to disrupt their meetings.

Chartists Temperance Chartists were a stream within the Chartist movement, who were campaigning for the right of working men to vote. Temperance Chartists wanted to persuade the elites that the working classes were sober and responsible enough to be given the vote.

Political parties The National Temperance Association Federation was associated with the Liberal Party. The Liberal Party passed the Defence of the Realm Act in 1914, under which pub opening hours were licensed and beer was more heavily taxed.

Temperance hotels

Temperance hotels provided accommodation and refreshment without the provision of alcohol. As the movement spread throughout the UK the number of temperance hotels and tea rooms increased. Many public houses and hotels in areas where temperance had become a significant influence struggled. The solution was adaption and alteration.

The Temperance Hotel at Scruton was formerly a public house called The Farmer’s Arms. In the early 1900s the business changed from a pub to a temperance hotel. The 1911 census shows that it was occupied by John Fothergill and his family. After John died in 1917, his wife remained at the property and, in 1921, was running it under the same name, although it seems to have been a boarding house rather than a hotel. Her guests at the time of the census were a widowed plate layer and his four children.

Left: Scruton Temperance Hotel (formerly the Farmers’ Arms Inn) [ZZF 4/6/3]; Right: Old Black Horse Temperance Hotel, Ripon [Ripon Re-Viewed collection, A3908]

The Old Black Horse Temperance Hotel, Park Street, Ripon. The Black Horse had traded as a public house from around 1822. It is believed to have become a temperance hotel in the 1890s following the death of the last licensee, John Wells, in 1891.

Meets and events

Like many non-conformist religious groups, temperance leaders promoted public events and conferences to spread their message and to raise funds to enable the continuation of their work. Events such as the Annual Soiree at Settle often included entertainment in the form of music by temperance bands and plays with a moral theme. Societies used such events to raise funds for their premises and took the opportunity to enrol new members where they could. At meetings, addresses would be given by leading League speakers like John Nunn, who was known for challenging leading anti-prohibitionists to public debates.

Posters for a soiree at Settle [PR/SET 18/1] and meeting at Reeth [ZLB 35/405]

The 38th Annual conference of the British Temperance League was held in Scarborough on the 18th and 19th of June 1872. The conference had last been held there in 1859. Press recorded that ‘The event has occasioned considerable animation in that great watering place’. Open-air lectures were held in the week preceding before official sittings were held in a beautifully decorated town hall. The League reported 929 lectures given in the last year.

The British Temperance League Conference at Scarborough, June 1878 [SC115029]